I forced a bot to scout some of the best prospects in MLS. Here's who it thinks they play like.

A couple years ago, before the 2019 MLS season, friend of the newsletter Bob Bradley issued a challenge to Los Angeles FC’s best player, Carlos Vela: he wanted him to play like Lionel Messi.

Which is, you know, a pretty wild thing to say. People memed the hell out of it. But then the season started and Vela went out there and … basically was Messi? He had the best attacking season in MLS history. He scored a ton of goals. He set up a ton more. He dribbled defenders. He progressed the ball with passes and carries. He knifed through defenses while bouncing one-twos off his teammates. He even did all this as an inverted right winger in a possession-heavy, high-pressing 4-3-3. As Caleb Shreve put it for Statsbomb, “Nobody's Lionel Messi, But LAFC's Carlos Vela Sure Is Trying.”

What does it mean for one player to be like another one? It’s a trickier question than it sounds. Was Vela like Messi because of all the scoring and assisting? Because of their similar positions? Because LAFC’s playstyle had some similarities to the old, good Barcelona? Or was someone else — Kylian Mbappé, say — more like Messi than anyone in MLS could be, despite their different playstyles, because at least Mbappé put up elite numbers at the highest level?

The answers to these questions matter because people are going to compare soccer players to other soccer players whether we know what we mean by it or not. Especially in recruiting, where scouts and coaches and sporting directors have to give each other some idea of a player without writing a Tolstoy novel about him, it’s common shorthand to compare him to someone everyone already knows. The prospect being described and the famous model player in the description are almost by definition not going to be as good as each other. The point isn’t to say “this player will be as good as that player,” it’s “this player will be however good or bad he may be in the same role or style as that player.”

Why am I telling you all this? Well, I’ve been thinking lately about similarity scores.

Player similarity scores are data analytics’ equivalent of a scout’s player comparison. Practically every recruiting platform offers some mysterious algorithm that promises to point you to the next Paul Pogba or the Moldovan Mbappé. These scores feel easy to understand. Right winger wandered off on a Paris vacation? Just type his name into a search box and a list of comparable players pops up.

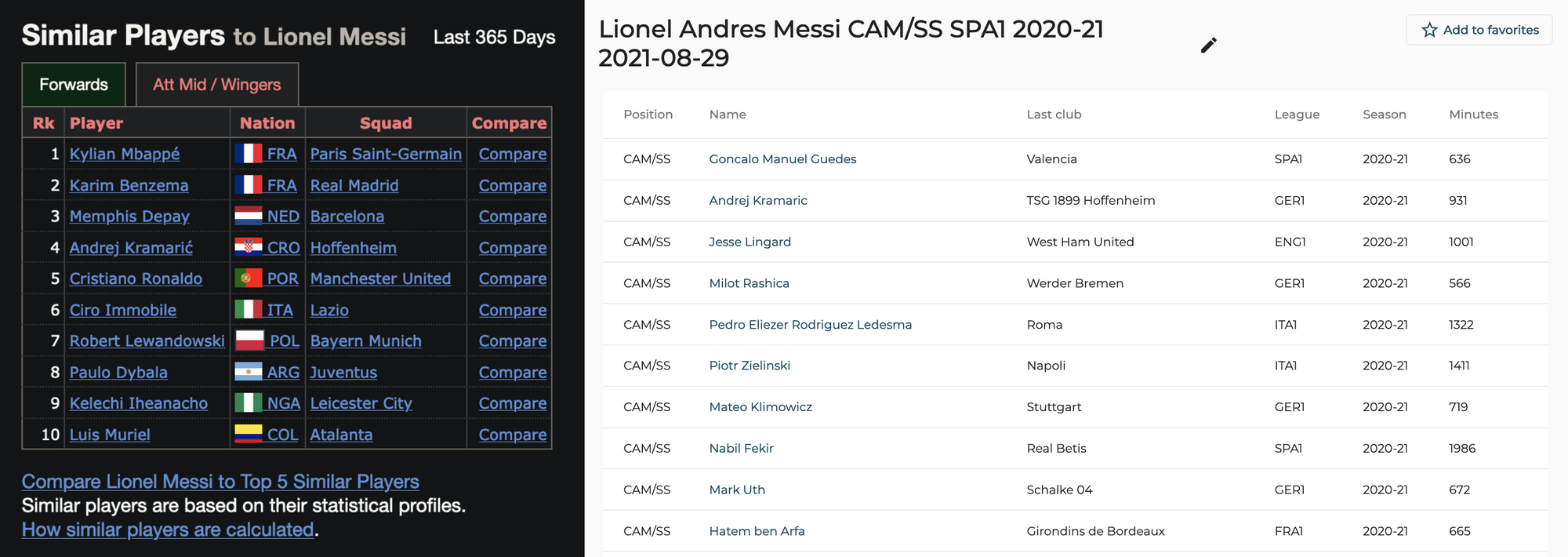

The thing about these algorithms is that a lot of them seem to be — how do I put this delicately? — complete horseshit. It’s not just that the results are bad, it’s that you can’t tell how or why they’re bad, so you’re just supposed to take it on faith that Lionel Messi is a dead ringer for Hoffenheim’s Andrej Kramarić. Translating soccer playstyles into stats is hard enough, but mashing a bunch of those stats into a ball and trying to match players with one number is even sketchier.

So of course I wanted to be sketchy myself.

Mapping Attacker Styles

I’m going to try not to dwell too long on the nerd stuff here, because I’m really more interested in seeing if my results mean anything by looking at players who the computer thinks are similar.

The technique I’ll use for mapping player styles is the same one from the Seven Styles of Soccer, a “dimensionality reduction algorithm” called UMAP. The general idea is you dump a bunch of player stats into the mixer, UMAP figures out how they're related, then it flattens everything out into a map where the most similar players are grouped together in little neighborhoods (even though the overall city layout doesn’t really matter).

This is also how Mike Imburgio and Sam Goldberg did their playstyle clustering for DAVIES, and I’m mostly going to copy their homework here. What I like about Mike and Sam’s method is that they were careful to distinguish between the three different concepts that can go into a player comparison — a player’s role, type, and quality — and did their best to only compare players along the first two.

The first step of the process is sorting players into broad position groups, which I did using FBref’s data on touches and pressures by third, normalized by team rates. That gave me a map that looked like this:

Bear in mind that these aren’t actually “position groups,” because I didn’t give the algorithm any position labels, but just from where players do their touches and pressures, UMAP was able to sort center backs from fullbacks from everyone else. The “everyone else” blob didn’t break up quite as cleanly as I wanted it to, but you can still see midfielders (blue) on one end, strikers (green) on the other, and attacking mids and wingers all mixed together (pinkish) in the middle.

I could have divided this map into anywhere between three and five position groups, but in keeping with DAVIES I went with four. A clustering algorithm called GMM split them up like so:

The names on the plot above are the players our clustering method was most unsure about, and it’s exactly who you’d expect to find along a midfield-attacker fault line: guys like Pedri and Paul Pogba just on the orange attacking side of the line, Luka Modrić and Leon Goretzka just on the purple midfield side. Danilo, one of the prototypical elbow backs, falls somewhere between the center backs and fullbacks. So far, so good.

Since this letter’s more about testing the player similarity concept than assigning everybody a playstyle, we’re going to toss out everyone but the attackers for now.

For the next stage, in keeping with the DAVIES method, we can run a second round of mapping using a totally different set of stats specifically chosen to help tell attackers’ playstyles apart. It took me a few days of experimenting at this stage, but I finally got a map that felt about right to me. Here are a bunch of players from top teams in 2020-21, along with every current MLS attacker born after 1997. You’re gonna have to zoom in on this one:

Up, down, left, and right don’t mean anything here. It’s not even necessarily important that attacking mids are toward the toe of the boot while wingers are up on the ankle, closer to the strikers — the arrangement of those groups could easily have been the other way around. The important thing is that similar players are supposed to be next to each other, and we’ve already got one sign that it’s working: Neymar and Messi are right on top of each other every season, off on their own stylistic island from everyone else.

How did the different player stats I chose combine to produce this map? Hard to say, but simple heatmaps can give us a rough feel for how things are sorted:

Okay, okay, enough with the algorithm talk. Can this thing actually give us player similarity scores that don't suck? I wanted to test it out by picking pairs of players next to each other on the map and trying to figure out exactly why the computer thinks they’re similar. Starting with five of the best young prospects in MLS, I found a famous player nearby to compare him to. If this thing’s working like it’s supposed to, I ought to be able to stroll into any sporting director’s office and describe the kid by pointing to a star who plays like him. But is it working?

To give us a better idea of where the comparisons are coming from, here’s a heatmap that shows how each player scores on the different stylistic metrics that went into the map. We’ll run through each match one by one. Remember, the idea here is not that our MLS player is or ever will be as good as his European counterpart, only that they try to do similar things with the ball:

Djordje Mihailovic is .... Josip Iličić

These guys are a good example of why roles are more important than positions. Iličić is a second striker and sometime center forward for Atalanta, while Mihailovic plays attacking, central, or even defensive midfield for Montreal. Shouldn’t they be on opposite sides of the map?

A quick glance at where they take their touches will answer that. Iličić likes to drop to the right in Gian Piero Gasperini’s wide diamonds and work from the sideline to the top of the box. Mihailovic drifts left and winds up covering a mirror-image triangle of the pitch. Filtering players by nominal position wouldn’t tell you these two have basically the same job.

It’s not just where they play, it’s how they play there. Mihalovic and Iličić are both heavily involved in their team’s attacking possession. They’ll venture outside the block to collect the ball and look to play a progressive pass first, but if it’s not there they’re happy to switch the point of attack. One difference is that Iličić is happy to cross to Duvan Zapata or Luis Muriel, while Mihailovic likes to break down defenses head-on. Use some imagination and you can see why he’s the closest MLS U-23 to our map’s Messi-Neymar island, but at 22, Mihailovic isn’t just a prospect: his goals added already puts him in the top five MLS attacking mids since the start of 2020.

Jesus Ferreira is … Kevin De Bruyne

Yeah this one’s a stretch, quality-wise, but separating style from production is exactly what we’re trying to do here. Ferreira broke through as a teenage center forward but by 20 his attacking role looks a lot like De Bruyne’s: drop into midfield, spray it long, then get upfield and put the ball in the box from a central area. The difference between these two and the Mihailovic-Iličić pair is that Ferreira and De Bruyne dribble less and don’t arrive in the penalty area much themselves. They’re less wide creators than something closer to a pure No. 10.

One charming quirk of MLS is how persistent the classic No. 10 role is, I guess because defenses haven’t squeezed the space between the lines like in Europe. No matter how many different ways I messed with the map, a clump of high-profile attacking mids (Maxi Moralez, Diego Valeri, Emmanuel Reynoso, Victor Vázquez, Carles Gil, Mauricio Pereyra — the list goes on) stuck together, while only a handful of players from top European clubs tended to show up nearby (most often Bruno Fernandes, Hakan Çalhanoğlu, and Luis Alberto). Ferreira’s anemic attacking output probably won’t earn him a move overseas anytime soon, but at least he’s in a league that will love him for what he’s becoming.

Caden Clark is … Marcos Llorente

Clark’s a tough one to pin down. At 18 years old he’s already scheduled to move to RB Leipzig; he’s obviously talented, it’s just not clear what kind of talent he’ll be. He grew up in a Barça academy in Arizona before going pro in the Red Bull system, so his formative years have suffered from a little bit of stylistic whiplash — it’s got to be weird to go from rondos and tiki-taka to Rangnickball and a 66% pass completion rate. It doesn’t help that the team he’s playing with has been in freefall since Jesse Marsch left New Jersey in 2018.

According to our map, the way Clark’s played there resembles … Atlético Madrid midfielder Marcos Llorente? Hm. The similarity seems to be based on their moderate midfield involvement, generally positive passing, and lots of crosses into the box. It sort of makes sense that two midfielders in fast, free-form attacks would have comparable on-ball traits, but they don’t look all that similar on the pitch. Llorente likes to lead straight-line fast breaks up the right side in front of Kieran Trippier and will occasionally tuck in to shoot from the top of the box, while Clark bounces all over midfield (and I do mean bounces — he seems to be permanently halfway off the ground), only flaring out to the wing to finish a move. This seems like a case where we might want to tweak some features, because better statistical profiles should separate these guys a little more.

Diego Rossi is … Kai Havertz

One worry with style comparisons based on aggregate season stats is how it will handle players who change positions, so it’s gratifying to see two forwards who split time between the wing in a 4-3-3 and a flexible striker role in a three-back system land next to each other on the map. Maybe it’s the product of averaging, but neither Rossi nor Havertz stands out much in our chosen stats except for their low expected assist output per touch. Even when they’re on the wings, they don’t cross or switch much, and they’re more likely to receive a dangerous pass than to play one. Is that enough to say they’re similar players? I don’t know. This won’t show up in the algorithm, but the thing that really sells the Rossi-Havertz comparison is the sense that they’re two of the most valuable young attackers in their leagues who aren’t quite living up to their full potential right now.

Tajon Buchanan is … Kingsley Coman

The heel of our map’s boot is the dribbling wingers, where you’ll find new Club Brugge signee Tajon Buchanan not too far from Bayern Munich’s dribbliest winger, Kingsley Coman. (Leroy Sané and Serge Gnabry show up over closer to the laces, with the box-crashing wingers). It’s not just that Coman and Buchanan take players on — Sané does that too — it’s that they beat them up the sideline for progressive runs and crosses into the box. Coman’s two-footed enough to provide wide service even on the left, where Hansi Flick liked him, but new Bayern manager Julian Nagelsmann wants to use him as a natural right winger, the same role Buchanan plays for the New England Revolution.

As for differences, Buchanan’s a lot less likely than Coman to play long passes or switches in the final third, which might have less to do with the players’ natural tendencies than their teams’ different attacking styles. That’s one difficulty with this method: we can’t totally strip out team effects, so the style map can give us an idea of how a player used his touches in the past but not how he might do it on a different team or in a different role. Guess we’ll find out when Coman completes a season on his new side and Buchanan gets to Belgium.

Taty Castellanos is … Luis Suárez

There’s a running joke in the groupchat about how smitten I am with New York City’s 22-year-old Argentine striker. He arrived in MLS as a 19-year-old winger who was athletic but raw, without the ball skills to really flourish out wide. Three years later, a long-term injury to the team’s starting striker has given Castellanos time to develop into the most complete center forward in the league. He shreds defensive lines with constant runs at all angles, ducks shadows in the box, hassles center backs, holds up play, presses like a maniac, and flops like that kid you hated in rec league. He’s a complete pain in the ass to play against, and I mean that in the best way.

I’ve got a feeling that the player he’ll most resemble in a year or two is his City Group doppelgänger Ferran Torres after Pep Guardiola is done converting the Spaniard into a striker. But Taty is farther along the positional curve and already shows up in the neighborhood of Robert Lewandowski and Luis Suárez on the style map. Even though Taty takes a higher share of his team’s touches than Suárez, who mostly pops up to finish Atleti’s fast breaks, his xG per touch is even higher than Spain’s golden boot winner. Neither player has particularly good close control, but they’re creative quick passers who are more likely to set up chances than the names along the map’s northern poacher coast. You can see some team style differences here too: Suárez plays longer passes in a more open attack, while Castellanos plays shorter in the middle of a compact, high-pressing side. (Not unrelated: Taty plays relentless of defense and Suárez plays none, but our map isn't worried about defense at all.)

So … did the player similarity thing work?

I mean, you can zoom around on the big map and tell me, but my feeling is that the answer is a resounding “sort of.” It's hard to say whether my similarity scores are more or less full of shit than anyone else's, but at least I know how these work. The algorithm is clearly doing a decent job of sorting players into general roles; on the other hand, I’m not sure FBref season stats are ever going to be a delicate enough instrument to measure the nuances of individual playstyles.

Funnily enough, while I was in the middle of writing this letter a nerd fight broke out over a new paper whose author argued on Twitter that UMAP is nothing but “specious art.” Maybe that’s true if you’re doing real science with it — I’ll wait for the scientists to sort that out. For soccer, at least, its ability to separate out how players play still seems pretty magical to me. The problem with using it for similarity scores is that any slight change in the stats you use can cause pretty drastic changes in who’s next to who, and how do you know which stats are the right ones to use?

You don’t. You never will. There are no “right stats.” There’s only good judgment, careful review, and a lot of trial and error. I think the best way to do this kind of thing is to work out playstyle clusters that make soccer sense and then compare players within those clusters using plain old xG or progressive pass percentiles or whatever. Which is pretty much what Imburgio and Goldberg already did with DAVIES — and they even built an app for it. Oh well, at least we learned a little about some promising MLS kids so you can sound smart when they get to Europe. ❧

Further reading:

- Mike Imburgio and Sam Goldberg, Introducing DAVIES: A framework for Identifying Talent Across the Globe (American Soccer Analysis)

- Tony ElHabr, Tired: PCA + kmeans, Wired: UMAP + GMM

- James McMahon, The Poundshop Messi Machine (Autogol)

- Harsh Mishra, This notebook will help you walk through the UMAP + GMM implementation on fbref data. (Google Collab)

- Caleb Shreve, Nobody's Lionel Messi, But LAFC's Carlos Vela Sure Is Trying

Image: John Stezaker, Psycho Montage III (The Mirror)

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.