Leipzig returns to Rangnick ball

One thing you should know about RB Leipzig’s new American manager Jesse Marsch is that he loves to drop German words when he’s speaking English. This is apparently not because he went to Princeton, although that is a little suspicious, but because he craves exactitude. Defenders don’t “go in,” they reingehen. Attackers don’t play up-back-through, it’s steil-klatsch-steil. He wants a common language with his players, a jargon everyone understands. He’s a details guy, our Jesse.

When he’s speaking German to his players, though, his favorite word is “fucking.” Dis ist nicht kein fucking Freundschaftsspiel, he tells his old Salzburg team in a halftime speech against Liverpool, and you only have to understand the word he didn’t know how to translate to get the point. Marsch’s game is about intensity. It’s about going hard even when you make mistakes. Press hard. Tackle hard. Transition hard. Fuck the details.

He’s probably getting a lot of mileage out of that word right now, I’d imagine, because Leipzig is making a lot of mistakes. In this weekend’s paid letter I wrote about Marsch’s way of playing “against the ball,” which his players are struggling to execute at speed after a couple years of more controlled positional play under Julian Nagelsmann. Here’s a video from the letter on some of Marsch’s pressing principles:

And here’s a complete catalog of Leipzig’s tactics in possession:

Nah, there are ideas worth taking seriously behind Marsch’s soccer, and for my money one of the most interesting questions of the young season is whether Leipzig is right to move away from playing more like the best teams in the world to get back to the transition-based style that defined the Red Bull empire under Ralf Rangnick. I hope you’ll become a paid subscriber to read about it.

Sané in the driver's seat

One of the teams to stomp Leipzig during their slow start is Nagelsmann’s Bayern Munich, who have vaporized their last month’s worth of opponents by a combined score of 31 to 1. Their expected goals tally through five rounds of the Bundesliga is nearly 20 percent higher than Liverpool, the next-closest team out of all 98 in the top five leagues. At this rate Bavaria might have to cancel Oktoberfest due to sheer exhaustion from doing the can-can.

Nagelsmann hasn’t changed all that much from Hansi Flick’s attack, which was already the best in Europe last season, but one notable beneficiary of the coaching change has been Leroy Sané, who’s back on his natural side after Flick’s failed efforts to convert him into a Bayern-style inverted winger. Can you blame the guy for trying? As I wrote about this summer, left-footed left wingers are pretty uncommon:

Grace Robertson wrote a good newsletter this week on natural wingers that touched on the Sané sitch:

As a left-footed winger who can really strike the ball well, the comparisons to Bayern legend Robben were obvious. It was something Sané wanted. “I usually played on the left at City,” he explained, “but as a youth player and at Schalke, I played on the right. My favourite position is on the right wing. I feel most comfortable there.” But he didn’t look like he was most comfortable. Sané’s game is about dribbling off his left foot and shooting straight across the face of goal with power. As his new manager Julian Nagelsmann has said, “On the right, Leroy often has the situation that he wants the ball in his foot and then has to play with his back to the goal — he doesn’t have the best quality there. When he plays on the left, he has a little more depth, the game often in front of him, it is easier for him.”

So far it’s tough to argue with Nagelsmann's assessment. Compared to last season, Sané is carrying the ball farther and higher up the pitch, playing more dangerous passes, setting up more teammates, and finding better shots himself. He’s a shifty, jerky dribbler who never looked all that natural at the Robbenesque cut inside from the right, but he’s got a Pep Guardiola-trained talent for timing runs into the box to finish a low cross on his left. When Bayern is on a fast break, which is pretty much always, Sané sprints up the left wing to receive in stride and looks for hard square balls across the back line. Even on his natural side he’s not a traditional winger but a more modern type, the driving winger:

[Driving wingers are] wide natural wingers whose job is to stretch the defense off the ball more than on it. They stay as high as possible and hug the touchline to give the attack width, but they’re more like to dribble at a defender and square a ball across the face of the defense instead of around to lay in a cross. But where these guys really make their money is diagonal runs in behind a fullback to turn a throughball in the channel into the perfect cutback.

Keep those lederhosen-clad legs limber, folks, ‘cause there’s a lot more can-canning left to do this season.

Vini Jr. looking all grown up

Remember last month when I was worried about Real Madrid’s geriatric squad? Yeah, scratch that. Not only did they sign one of the world’s most coveted teenagers since then, but one-time wonderboy Vinícius Júnior has carved his name into Carlo Ancelotti’s eleven by playing like a grown-ass man. Here’s Om Arvind after Vini willed his team back against Valencia:

The interesting thing was, in terms of his dribbling this was maybe his weakest game of the season — only one completed dribble off five attempts. It wasn’t really coming off for him. And we talked about how there are other aspects to Vinícius’s game, like the dangerous off-ball runs and how he’s underrated about getting into good locations in the box.

As Om’s Managing Madrid colleague Matt Wiltse wrote about last week, that work in the box is where Vinícius has been proving himself to his manager. “Vinicius is very good in one-on-one situations. As for scoring goals, I’ve told him that it’s rare to score after taking five or six touches,” Ancelotti said. “To score, you need one touch or maybe two maximum. You have to be in the box.”

At 21, Vini is actually getting on the ball in the box less than in his teenage seasons yet producing twice as much xG. Some of that is down to better ball control and a quicker trigger, but some of it is his movement to get in better spots before he even receives the ball. The great English striker Jimmy Greaves, who passed away this week, explained it as well as anyone: “What I had to do was get in the box 500 times a season. One hundred times I'd connect. Fifty times the goalkeeper would save it. Half of the rest would go in and 25 goals a season would do me — just by making sure I got in the box 500 times.”

At heart Vinícius is still the classic Brazilian winger who wants to lounge out by the sideline, let the ball roll to his feet, and melt five defenders’ faces on the dribble. That’s fine, mostly, because he can melt faces better than all but about a dozen people on the planet. But when he learns to scramble defenses with his on-ball threat and then follow up with a run like this —

Well, this goal-a-game pace is the kind of thing a kid could get used to, yeah?

Gerard Piqué is goals

Speaking of arriving in the box, Gerard Piqué fulfilled a lifelong dream this week when he was brought on to play, uh, striker?

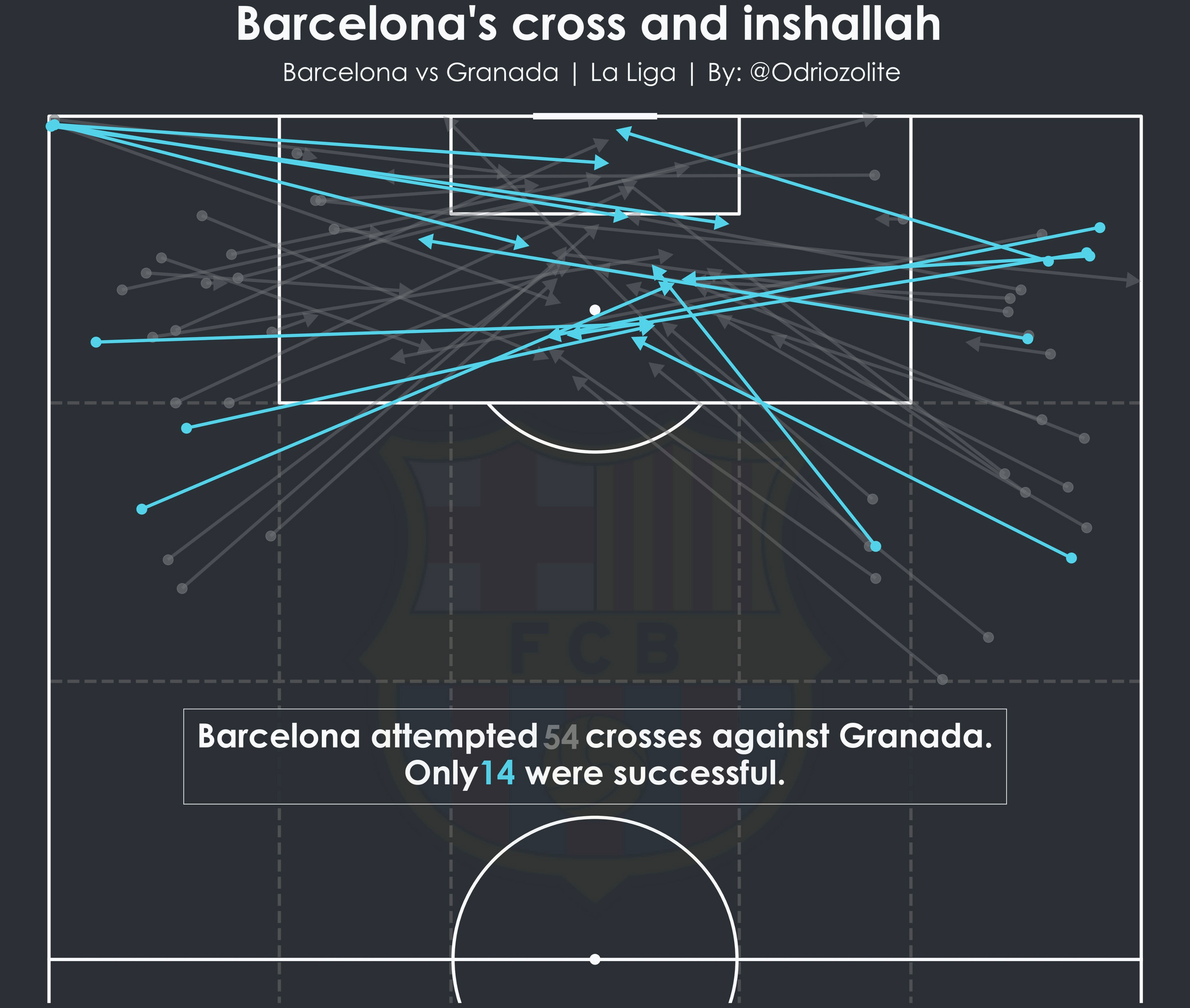

Sure, he’s played up front before — he has 31 career non-penalty goals, 12 from open play, every one of them celebrated like it was the best thing since dating Shakira. But Striker Piqué was always an ad hoc thing, late in games when he got too desperate or bored to stay home at center back. This was different. After their early away goal sent Granada into the bunkers, Ronald Koeman only had one plan: cross and cross and cross again, 54 of them by the final whistle, a number Barça had hit only once in the last 15 years. But who was supposed to get on the end of them? Martin Braithwaite is injured, Memphis Depay is the same height as Pedri (no, seriously, look it up), and everyone else has moved on, so Koeman finished the second half with a Piqué-Luuk de Jong forward pair fielding endless fly balls. It’s a miracle the Camp Nou ground didn’t open to swallow everyone whole.

How did it come to this? In a paid letter, I talked to Simon Kuper, whose new book The Barcelona Complex gave him an up-close look at how the club works, about the business, personal, and institutional failings behind the El Chiringuito clips. I was curious whether Barça’s standing as the last real democracy among the superclubs makes it uniquely susceptible to bad decisions:

“The president is born in the town, typically he’s going to die in the town,” Kuper said. “He wants to make decisions, buy players, keep players that will keep his children happy, the waiters at the local café, his business partners, the people he went to school with, the people he runs into on the street.”

If there’s one thing Piqué has never been shy about his ambition to become, besides a target forward, it’s president of FC Barcelona. And why not? It’s more likely than Monday’s second-half lineup. ❧

Thanks for reading space space space! Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to get twice as many letters and access to the full archive.

Image: Toulouse-Lautrec, Moulin Rouge-La Goulue

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.