Pandemic weirdness. Tactics trends. Rule changes. Nerds ruining the game. Soccer is changing, and numbers can show us how.

Goalkeepers don’t send it long anymore. If you asked me how soccer works in 2021, that’s probably where I’d start. I think it might be the key to the whole story.

Just three seasons ago, according to FBref’s Statsbomb data, 79% of the average team’s goal kicks in the so-called Big Five Leagues — Spain, England, Germany, Italy, France — were “launched,” or kicked farther than 40 yards. Today that number is 57%. In open play, back in 2017-18, a little more than half of goalkeepers’ passes were launched; in each of the last three years that share has slid steadily in every league save one, at the top, middle, and bottom of the table alike, to an average of 43% this season. Long distance relationships never last.

There’s no one simple explanation for the shift. Part of it comes from the new goal kick rule, which changed set pieces and set off an ongoing wave of innovation in building from the back. Some small part of it may be driven by the growth of data analytics, which seem to favor short goal kicks. A lot of it’s plain old copycatting: a few of the best teams insisted on playing out from the keeper, they won, and others followed. Then there’s the pandemic schedule, which has pulled tired presses back and given exhausted attacks some breathing room to take it slow in the buildup. Pretty much every major influence on how soccer has changed these last few years — the rise of positional play, rapid rule changes, games played on spreadsheets, games played in empty stadiums — has had a hand in how keepers kick. If you look hard enough, launch percentages explain everything.

Of course it’s silly to try to describe the evolution of soccer in a few averages, but not much sillier than the other stories we tell ourselves about the history of the game. We know, somewhere in our collective memory, that teams don’t play quite the same way now as they did five years ago, and the way they played then looked very different than a decade or two earlier. Tracing that development has traditionally been a kind of folklore, a patchwork quilt of big games and great players half remembered, of colorful quotes endlessly repeated and shamelessly misattributed because they felt like they summed up some footballing zeitgeist.

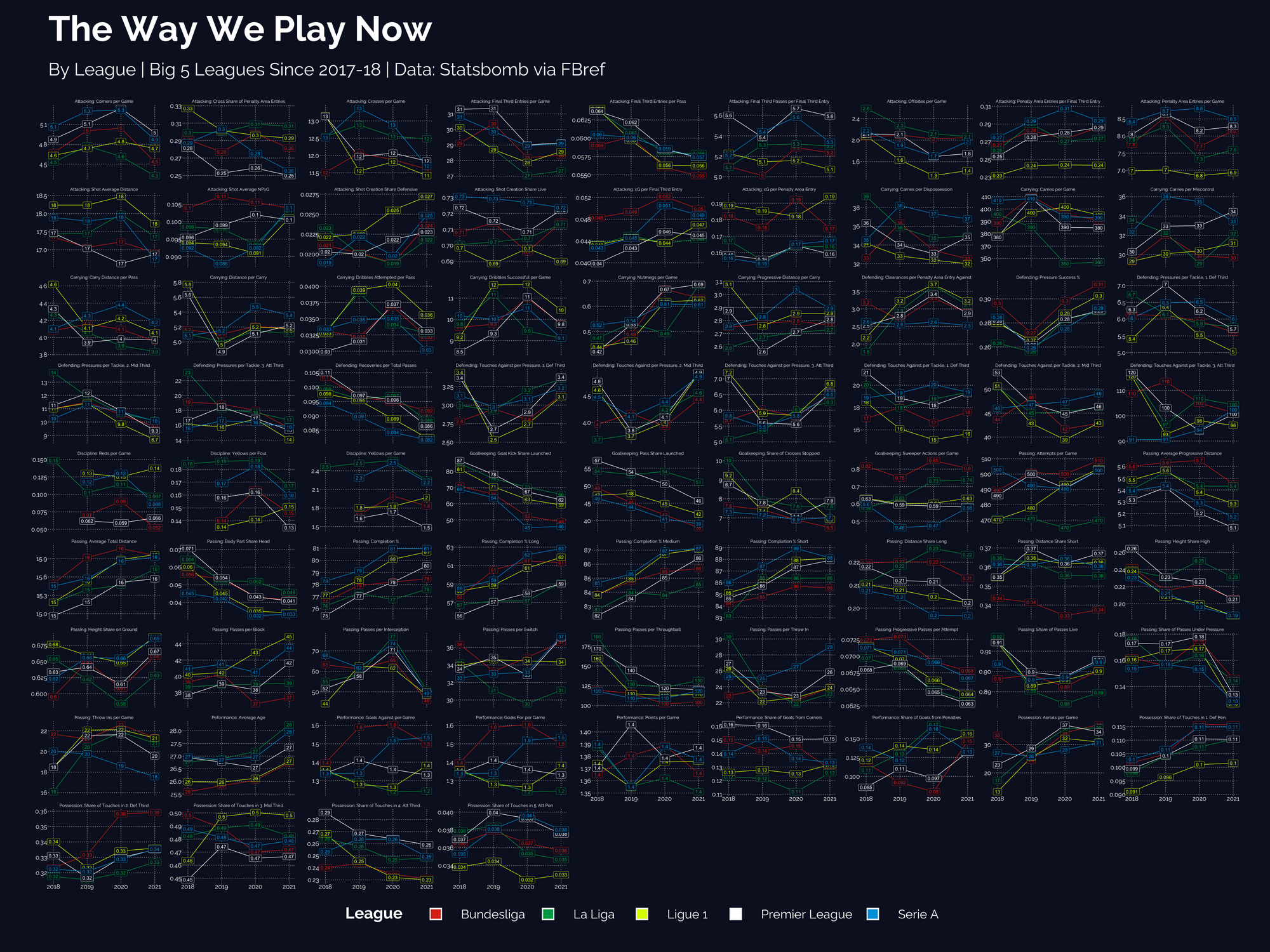

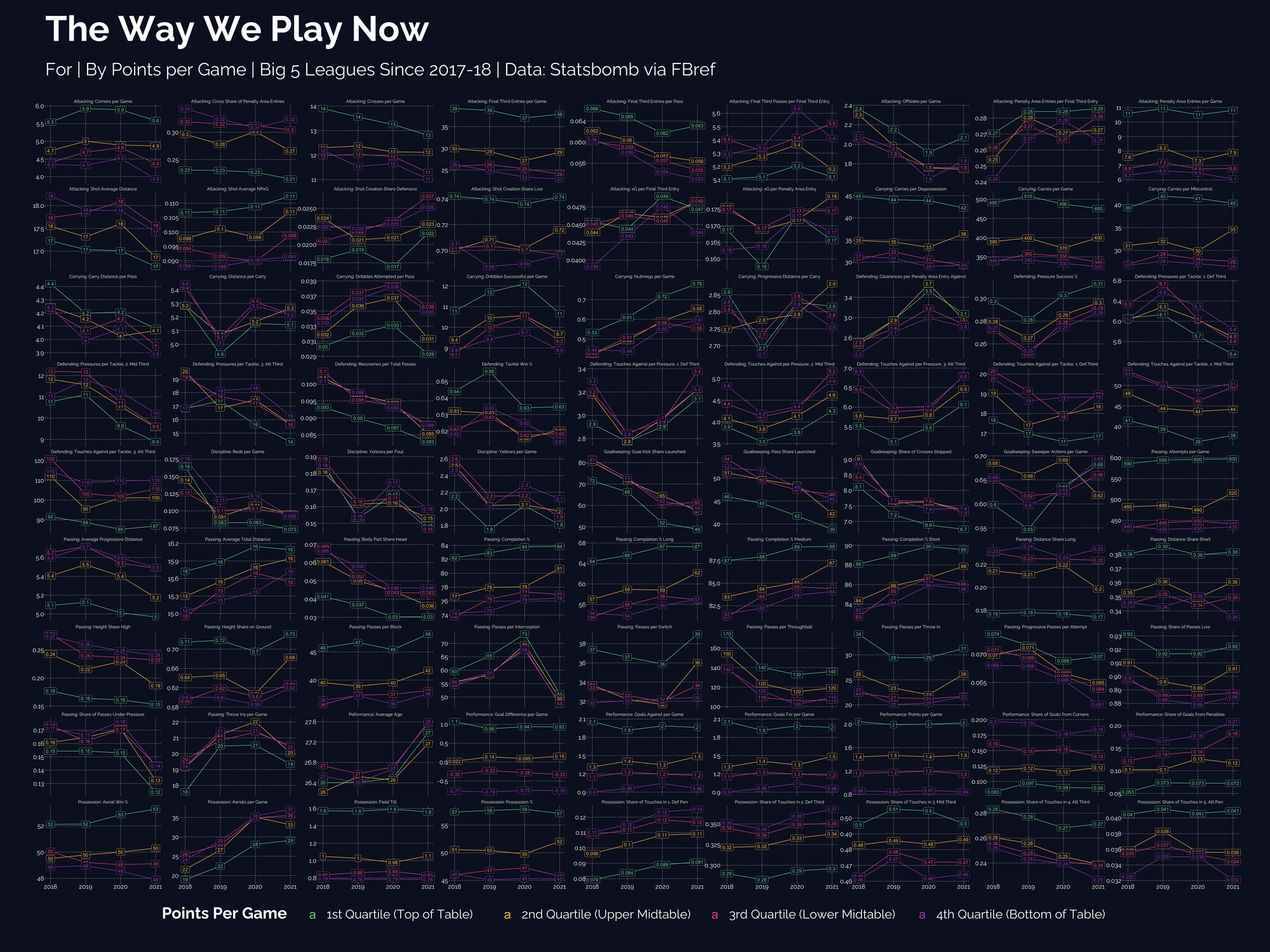

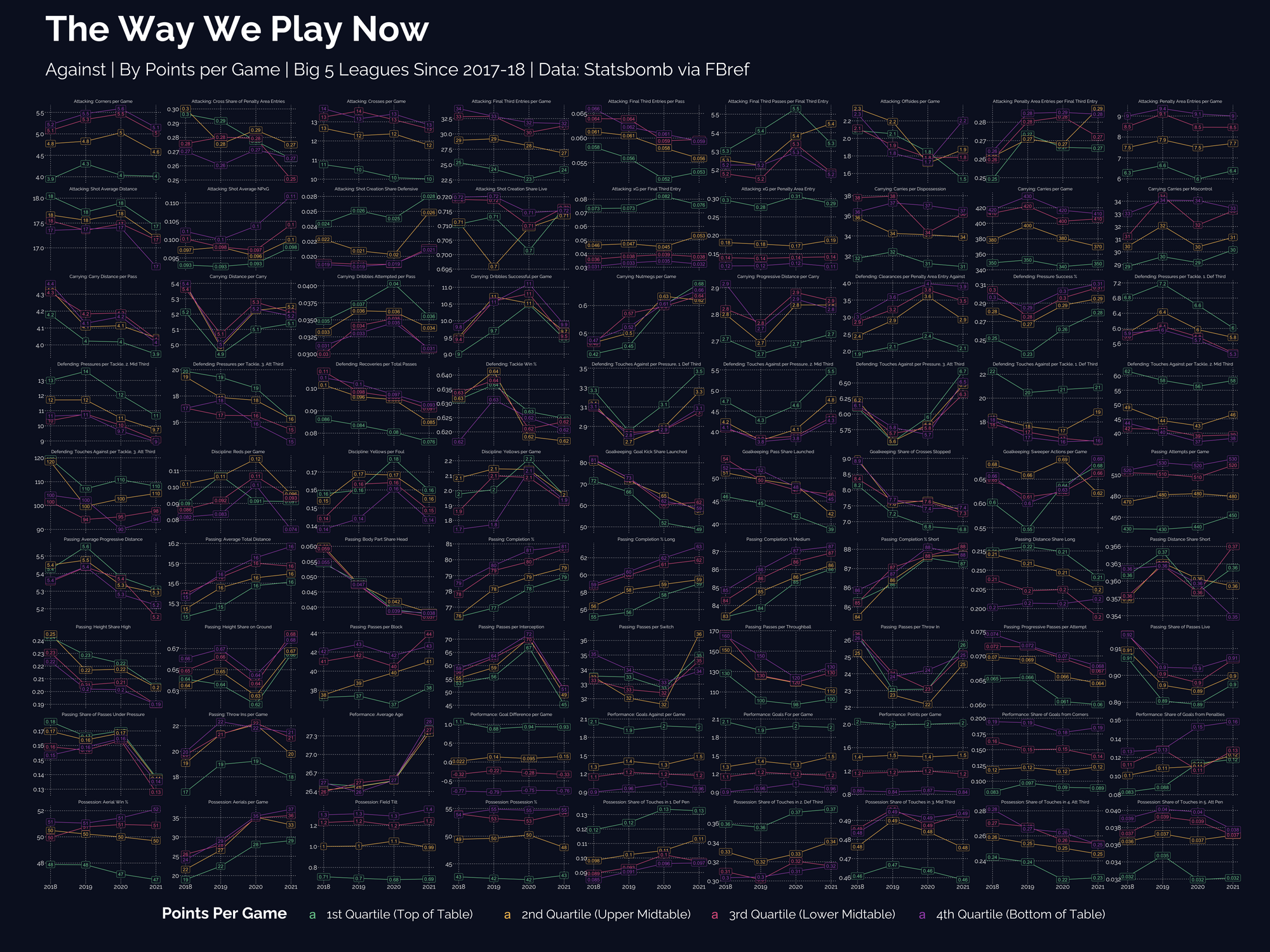

I want to try that with numbers. FBref’s detailed stats for top leagues go back only as far as 2017-18, but boy are there a lot of them. Using Jason Zivkovic’s handy worldfootballR package, I grabbed every kind of team-season-level table I could, then mixed and matched and carved them up by various denominators to get a suite of about 80 custom metrics that felt like they might tell me something about the game. I plotted their movement over time a few different ways: by the overall average, by league, by points per game quartile. I’m not going to put you to sleep with significant digits for the rest of this letter, but for you sickos who want to see where this is all coming from, zoom way, way in and go to town.

Let’s start with passing, yeah? There’s more of it than there used to be. France has used the pandemic to catch up with the big boys in attempts per game — Rennes, Monaco, and Lille joined PSG in the top twenty this season, with Nice and Lyon hot on their heels. Only Spain, where a growing number of teams are playing some version of José Bordalás’s direct-passing, high-pressing other football, lags behind. There hasn’t been much change in pass counts at the top or bottom of the combined table, but upper-midtable teams are passing a lot more than they were a year ago. The gap between the top two tiers is narrowing in other places, too. Maybe it’s just a ghost game thing, but it looks like clubs on the fringe of European competition are playing more like the elite.

Part of the reason more passes are being attempted is that — and please hang onto your hat for this one — more passes are successful. Completion rates are up for passes of every length. It probably helps that high passing is out of vogue outside of Spain, and headers are down as a share of passes everywhere. Passes have gotten longer each season, but they’ve also gotten less progressive. Must be more switches, right? Actually, those are down this year. The longterm trend is toward playing lower, slower, longer, and wider, without hurrying too much either vertically or horizontally. We’re in the ball circulation era now.

The chilled out passing corresponds to a decline in defensive pressure in every third of the pitch, although there’s a little bit of a chicken and egg thing going on there. Are teams closing down less because passers are circulating more, or is it the other way around? Whichever one came first, the pandemic’s definitely playing a part. The number of passes per interception has fallen off a cliff this year — by stepping back a little bit from the ball carrier and letting opponents play on the ground, defenders are picking off more strays. Possessions have spent more time in the defensive third this season, and with defenders keeping their distance, dribbling is way down.

But not every trend is about the pandemic. Some are probably more about the rules, like the drop in offside calls and spike in the share of goals from penalties in the two seasons since VAR was introduced. For some reason there’s no corresponding spike in cards, though, so it’s possible both the offside tally and the penalty share of goals are more about teams hanging back in possession and not getting into the final third as aggressively as they used to. Soccer’s complicated.

There are also more longterm trends, like an overall decline in crossing as an attacking strategy. Some of that could be influenced by analytics, which has traditionally been pretty unkind to crossing, although that picture gets more complicated the more in-game context you have. The asynchronous movement across leagues — Italy started crossing more one year while France and England crossed less, and Spain and Germany have stayed pretty much the same — makes it look like the natural ebb and flow of tactical trends. Most of those passing behaviors we talked about appear to have been changing even before the pandemic, so it’s hard to tell what’s a long term tactical swing away from early-Klopp heavy metal pressing and Rangnickisierung toward City-style juego de posición and what’s due to the general weirdness of the last year. Who can say which numbers might snap back to some old normal next season, with regular schedules and fans in the stands?

Even in our globalized modern game, national styles are still sort of a thing. La Liga passes less, carries less, and hits higher, longer passes. The Bundesliga hates short passing but takes a lot of touches in the defensive third. Serie A carries the ball more often, for longer distances, without getting dispossessed too much. Ligue 1’s young wonderkids love to beat guys on the dribble. (I was a little surprised to learn that Germany’s minutes-weighted age is lower than France’s, but then I remembered that Borussia Dortmund exists.)

I thought the numbers might show a widening gap between the best and worst teams as money has poured in at the top, or a shrinking gap this season when almost all the good teams started sucking for some reason, but neither one’s obvious. The only really interesting thing in the points per game charts was the convergence in a lot of stats between the very good teams and the only sort of good ones, which I don’t have an explanation for. Maybe the secret story of this season isn’t that the best teams got worse, but that other teams got better at playing like them. That might explain some things about indie darlings like Lille, Villarreal, and even Brighton, whose stylistic stats look similar to the Champions League semifinalists’.

It might not surprise you to learn that their keepers don’t launch many passes. ❧

Image: Georges Seurat, The Gardener

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.