The secret to finding undervalued talent is to play a whole different game.

Barnsley FC, a low-budget English club currently in a playoff for promotion to the Premier League, appears to be using data in a very different way than most clubs. I say “appears” because, like with most clubs, we don’t know exactly what their analytics operation is up to. What we do know is that — well, here are some headlines:

- “Moneyball comes to Barnsley as group including Billy Beane seals takeover”

- “Billy Beane: Who is he? What is Moneyball? Why Barnsley? What’s his net worth?”

- “Moneyball Gives Billy Beane-Backed Barnsley a Premier League Shot”

- “Billy Beane Has Lowly Barnsley on the Brink of a Moneyball-Fueled Promotion”

You get the idea. There’s this guy named Billy Beane — or as The Athletic helpfully identifies him, “Billy ‘Moneyball’ Beane” — who’s the main character of a bestselling book turned major motion picture called Moneyball. Brad Pitt played him in the movie. He’s a big deal now. He is also, as of 2017, a minority owner in Barnsley, which by association makes Barnsley a big deal now. Maybe there are other ways that Barnsley is a big deal in the world of the English Championship, but this is the way that gets them a feature in the Wall Street Journal.

The premise of Moneyball is that the Oakland A’s, a low-budget baseball team led by Billy Beane, were able to compete with richer teams by using data to find undervalued talent. That sentence is about the extent of what the buzzword “Moneyball” means in the popular imagination. Sometimes it’s boiled down to “doing sports analytics.” Sometimes it means “doing pretty much anything with data, in any context, as long as there’s money involved.”

But Moneyball, the book, isn’t just about using stats to find good players. Data scouting has always been part of baseball. The way Beane’s team overachieved was by changing what being good at baseball means, rethinking the sport’s century-old assumptions about which numbers mattered for winning games. By asking different questions of the data than other teams, they won with players everyone else thought were bad.

Most soccer clubs you’ll hear about “doing Moneyball” aren’t doing anything like that. They’re using stats to find players who are good at passing, dribbling, receiving in valuable areas, taking shots that are likely to score — in other words, good soccer players. The purpose of using data this way is simply to find good soccer players faster, cheaper, more efficiently, and from a larger talent pool than a traditional scouting department could manage on its own. If you do it right, this kind of analytics work should turn up guys that scouts would agree most teams should sign.

Barnsley is not like most teams. It’s debatable whether they play soccer at all. As Chris Russell points out in the video below, which I can’t recommend highly enough, a Barnsley match “bears closer resemblance to Slime Volleyball, a game popular in early 2000s high school computer labs.” The squad’s signature tactic under manager Valérien Ismaël is what Russell calls “the Barnsley Skyball,” which does what it says on the tin. Give any Tyke a ball and he will carry it straight ahead and then spray it, when startled by a predator, as high and far as possible, less a pass than a protest against gravity.

It’s not clear how Barnsley arrived at this approach to the game. One local podcaster told The Athletic that the club’s playstyle “represents the town and its heritage,” which seems like a mean thing to say about a pleasant-looking village in South Yorkshire. It may not be entirely true, since Barnsley’s ownership group has clubs in Belgium, Denmark, Switzerland, and France that reportedly play the same way. “All PMG sides try to take the ball in your half and do something in the chaos,” says an accountant quoted in the Athletic article, adding, “I know nothing about football. I watch it in the same way my mother watches it.”

The podcaster is right, of course, that England has a heritage of hoofball, lumping it to the big man up top rather than mucking about with all those fussy continental passing patterns. The accountant and his mom are correct about what Barnsley is trying to do: get the ball into your half and cause chaos. What the club has added to traditional Route One play is a ferocious press to make sure the ball stays in your half. Instead of using longballs to maintain a compact defensive shape, draw out opponents, and then attack the space behind them like a typical English underdog, Barnsley uses longballs and intense pressure to pin opponents deep in the most valuable part of the pitch, where any stray bounce is far more likely to help than hurt them. Who said you need complicated tactics to ascend to the Premier League? Chaos is a ladder.

The obvious point of reference for a network of clubs using direct passing and high pressing to compete on a budget is the Red Bull system, and it was no coincidence when Barnsley’s previous manager, Gerhard Struber, left the club last fall to coach the New York Red Bulls. (Barnsley’s ownership group has also hired from the Red Bull coaching staff.) An even better stylistic comparison might be the school of Spanish minnows trying to survive against Barcelona and Real Madrid by playing a maximally chaotic "other football." When two clubs in this group go head to head, like a Getafe-Eibar fixture last summer where the combined pass completion rate was 53%, it's about as close as you'll see in a top league to a Barnsley game. The only juego de posición these teams care about is field position.

But even that undersells just how deeply weird Barnsley is. According to Whoscored’s Opta data, no club in Europe's top five leagues had a lower pass completion rate this season than Getafe’s 66%. Barnsley’s was 58%. Eibar led the top leagues with 56 aerials per game. Barnsley had 66. Eibar put up 83 long balls for and 80 against per game. Barnsley attempted 84 per game, while opponents attempted an astonishing 102. You can chalk some of these numbers up to the sloppiness of England’s second division, where the bottom feeder Wycombe completes its passes at an even lower rate than Barnsley, but that triple-digit long balls against figure is 24% higher than the next closest team in the Championship. Barnsley doesn’t just play Skyball — they force the other team to do it too.

The simplest way to illustrate how Barnsley imposes its game is to look at free kick routines. I’m not talking about your typical set pieces on the edge of shooting range where coaches choreograph drills to get around the wall. I’m talking piddling whistles 80 yards back, somewhere south of the halfway line, where any other club would tap the ball sideways and get back to the business of building up. Not Barnsley. Almost every foul or offside flag outside the defensive third is an excuse for them to stack eight men in a tiny rectangle at the top of the opponent’s box and have a center back or goalkeeper lob an artillery shell into the mixer. Four Tykes charge into the box to stretch the defensive line; four stand ready for a second ball or a chance to counterpress. It’s such a simple, brilliant way to make a mess in the most dangerous part of the field that you sort of wonder why everyone else is doing free kicks wrong.

There are a couple reasons other clubs don’t do this, I think. One is that it feels reckless to shove all but one or two outfield players up around the other team’s box a dozen times a game just to hit and hope. Then again, that’s basically how attacks set up for corners, so what’s the big deal? The fact that most teams won’t attempt this kind of free kick until they’re chasing the game in stoppage time speaks to how they view the risk and reward, but maybe also to another, more difficult psychological block: it just looks dumb. When I tweeted a picture of a Barnsley free kick the other day, I had coach dads in my mentions telling me they’d be ashamed to let their U-12s play that way. Which is all well and good for development, I guess, but let me know when your U-12s are fighting for promotion to the Prem.

The reason Barnsley is unafraid to do bizarre free kicks, and basically all you need to know about why they’re so damn weird, is that they’ve gone all in on what I think might be an important analytical — maybe even philosophical — truth: it doesn’t actually make that much difference whether or not a pass is completed as long as you're in position to win it back. The only thing that matters as far as the table is concerned is whose goal the ball goes into, and which team has a player “on the ball” is generally less important to scoring probabilities than ball location and defensive disorganization. That’s especially true when the ball is a million feet in the air all the time and nobody’s “on” it at all. Imagine no possessions; it’s easy if you sky.

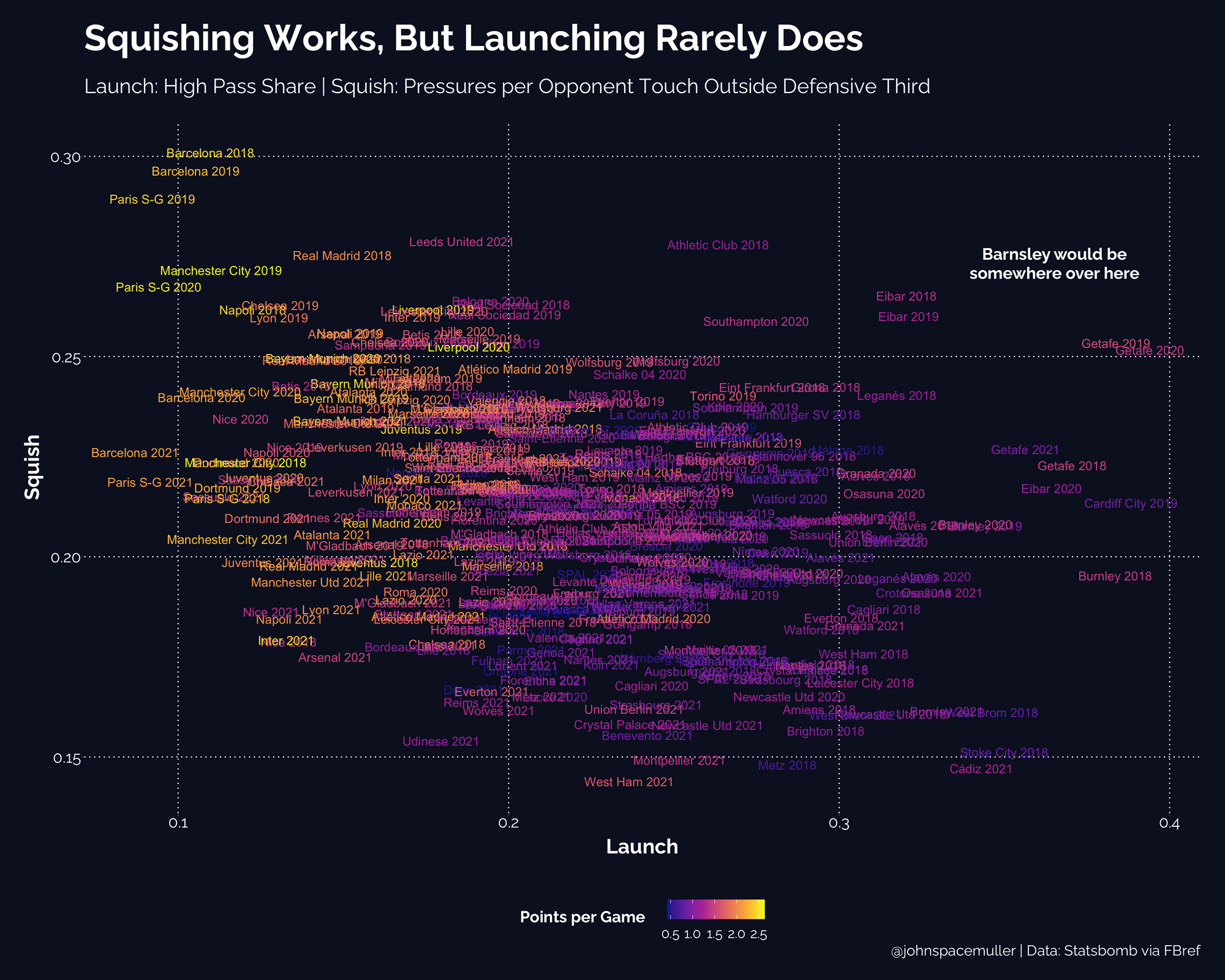

For the kind of people who think about sports in terms of probabilities, Barnsley’s style is seductive. "My football club would be the 'launch-and-squish' football club," the basketball executive Daryl Morey said at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference a few years back. "Launch [the ball] and press and squish, keep them in their end and look for turnovers. It seems like that style is coming when I watch.” Morey knows a thing or two about predicting analytics-driven playstyle trends. He’s famous for leading the NBA’s radical shift away from Michael Jordan-style midrange jumpshots toward more efficient three-pointers and layups (and so, so many fouls). Everyone plays this way now. There’s even a name for it that pays homage to Billy Beane: Moreyball.

Launch and Squish sounds clever in theory, but so far nobody’s made it work as well in top flight soccer as Moreyball has in the NBA. Getafe at their peak finished fifth in La Liga and made it to the Europa League Round of 16, beating Ajax before falling to Inter Milan. Eibar, a Basque club so tiny they got their red and blue colors from wearing Barcelona’s hand-me-down kits, punched well above their weight to hang around La Liga for a few years. But when they couldn’t keep up their usual high pressure during the pandemic schedule, both clubs sank to the bottom of the table this season. Squishing works for the best teams, but launching rarely does — in part because long balls tend to make it harder, not easier, to sustain a high press. As the influential coach Juanma Lillo, now an assistant at Manchester City, once said, “The faster the ball goes up the field, the faster it comes back at us.”

Despite all the attention to Barnsley’s analytics, I haven’t seen anyone at the club claim that Skyball is designed to maximize expected possession value or whatever. They could pretty easily have developed their style of play through simple tactics theory, no calculator required. Officially, Beane is a “silent partner” in the ownership group, which I guess means he doesn’t want people to think Brad Pitt and Jonah Hill are hunched over a laptop somewhere calling the shots. When club chairman Chien Lee talks how Barnsley uses data it sounds like any other modern scouting operation: “We are looking for players and coaches that play the style that we want, and that is very much a passing game."

But Barnsley’s idea of a “passing game” is the exact opposite of everyone else’s, and that’s where the Moneyball magic comes in. When you measure a pass’s success not by who gets on the end of it but by whether it helps you create danger near the other team’s goal, you can recruit for very different qualities than everyone else. For Beane’s baseball team, the undervalued skill that gave them an edge was a batter’s ability to draw walks. For Barnsley, it might be aerial ability, winning second balls, pressing, or just walloping the fuck out of the ball. Those are a lot cheaper to find on the transfer market than deft passing.

Take Daryl Dike. Back in MLS, Barnsley’s center forward was nothing special. Drafted out of college, where not many players go on to be top pros, Dike exceeded expectations by earning a lot of minutes for Orlando City last season and scoring eight non-penalty goals, good for ninth among MLS strikers. That got him a lot of attention as a USMNT-eligible rookie. But according to American Soccer Analysis, Dike’s scoring came on just 4.3 expected goals — an unusual stat line that would be a red flag for most data-savvy teams. By goals added, ASA’s model that estimates how much every touch changes a team’s chances of scoring and conceding, Dike was below average at passing, receiving, dribbling, and shooting — everything but defending and drawing fouls. An analytics department searching for skill on the ball or a talent for finding shots in the box probably would have advised their sporting director to look elsewhere.

And yet Dike’s been excellent for Barnsley. Sure, he’s still crushing xG models at a rate that’s almost definitely unsustainable in the long run. He’s still not great at most of the stuff we associate with “being good at soccer.” But he busts his ass on and off the ball, wins a lot of headers, provides good hold up play, and physically punishes defenders as a 6’1”, 220-pound wrecking ball of a human. He’s the perfect Skyball striker, but his talents are limited enough that a thrifty Championship club could borrow him on loan from MLS.

That right there is what Moneyball looks like. Barnsley wins ugly. They win cheap. They are not, in my opinion, a very enjoyable soccer team to watch. But they do win. Right now they’ve got the Championship’s 19th-most valuable squad according to Transfermarkt playing like its 5th-best team by FiveThirtyEight’s SPI. If a couple Skyballs bounce right and a couple Dike blasts rip holes in the net, Barnsley could find themselves in the Premier League next season, launching and squishing and inflicting whatever kind of chaos it takes to spoil Man City’s billion-dollar passing game. Who wouldn’t want to watch that? ❧

Thanks for reading space space space! Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support the project and get paid letters like last weekend's on what data can tell us about how soccer is changing.

Further reading:

- Matt Slater, From Barnsley to Belgium, the club owners taking on the elite with data, pressing and young players (The Athletic)

- JohnWallStreet, Moneyball Gives Billy Beane-Backed Barnsley a Premier League Shot (Yahoo Sports)

- Justin Harper, Data experts are becoming football's best signings (BBC)

- Mark Thompson, The *real* meaning of Moneyball (Get Goalside!)

Image: Simon Denis, Cloud Study (Early Evening)

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.