Welcome back to THE BIG BOOK OF BUILDUPS, space space space’s four-part special on how Champions League teams build out of the back. We'll wrap this up with part four later this week, also just for socios. Thanks for subscribing!

Every switch is a race. Against the flight of the ball, against gravity, against the give of the ground and the slick of the grass. Against pressure, against the speed of the defenders, but more than anything against how they think. All the rest of that stuff? You can’t plan it. You strike the ball well or you don’t, you’re faster than them or you’re not. The teams that are good at using switches in the buildup aren’t just the ones whose players can drive the ball across the field with the right weight and curl or sprint up the wing and cushion it in stride. I mean, that helps. But they’re also the teams that have a plan to sucker defenses in before playing over them, like that kid in elementary school who told you your shoe was untied and then ran off to the finish line. Who said the race had to be fair?

If it were easy, everyone would do it. Switches are so obvious. If rotation (shoutout to Day 1) is about manipulating the defense to carve little pockets of space inside it and pass-and-move combos (ayy Day 2) are about zigzagging through the press with third-man runs and acute angles, switches are simpler than that: they don’t go through the block at all, they go around it. Knock the ball to a guy on the weak side and the defense will have no choice but to scramble backwards. That little shift in momentum—claiming space and the initiative, making the other team regroup while you press the advantage—is how the buildup phase is won.

When you think about it, a switch is just the natural consequence of a tactical axiom that’s attributed (like every tactical axiom) to Johan Cruyff: a team in possession should make the pitch big, a team out of possession should make it small. The attack wants to spread the field and open as much space as possible, since the ball moves faster than the man, while the defense wants to stay compact and force longer, riskier passes. As the ball swings out wide and the defense shifts over to trap play against the sideline, there’s space on the other side for the team in possession to make the pitch big. That’s when switches happen.

I don’t want to spend the rest of this letter describing what you can see in the video, because the two basic types of switches teams use in the buildup are pretty easy to grasp. The less popular type involves stacking two players in a wide channel, usually a fullback and a winger or an outside center back and a wingback, and playing a safe switch to the one underneath. The more popular type is a diagonal all the way to the winger. What I want to talk about instead is: shouldn’t that be the other way around?

In my highly scientific sample of Clips I Saved From the Giant Buildups Rough Cut Because Interesting Stuff Happened in Them, half of the diagonal switches led to turnovers and none led to a shot, while none of the lateral switches led to turnovers and half of them led to shots. As statistical evidence that’s meaningless except for this: I reviewed 675 minutes of Champions League play plus stoppage time and not one switch to a winger in the buildup produced a shot.

Sure, there were some things teams could do to increase the chance that their diagonals might produce a shot. Juventus and Lazio were good about dropping an attacker into midfield right before the switch so that the opposite movement would draw attention and isolate the winger. Step two was having that dropping attacker turn and follow the switch upfield to support the winger for a pass, second ball, or counterpressing opportunity. This is all tactically sound as far as it goes and you can see in the video how it plays out. You won’t see a lot of PSG, who didn’t do this and wound up losing their diagonals as a result.

And yet even for the teams that did it right: no shots.

The reason diagonal switches in the buildup tend not to produce shots is—and I apologize in advance for the advanced analytics terminology here—they’re fucking hard. There just aren’t that many players who can reliably drop a 60-yard cross-field diagonal onto a teammate’s foot, or even into the generous buffer zone that a defense’s horizontal shift tends to allow a winger. Plus landing it there isn’t enough. You’ve got to hit the ball with enough pace that a defender can’t get under it and close down, but not so hard that the winger can’t control it. You want to lead your guy just enough to play him in behind the defense, but not so much that he won’t be able to catch up to it. The percentages are not pretty.

Even when cross-field diagonals connect, not much comes of them. The best you can usually hope for is that the winger will corral the pass and circulate it back to teammates trotting behind him to catch up to the play. It’s not exactly the hero ball it looks like. As Toronto FC analyst Devin Pleuler put it recently while explaining the poor risk-reward profile of switches: “In general, the more difficult a pass is, the more valuable it is. But it’s not a perfect relationship.”

The good news is that the imperfect value-difficulty relationship cuts both ways. If diagonal switches are all sizzle and no steak, lateral switches are more like … whatever the opposite of that is. They’re a lot easier to complete than diagonals and they just might be more valuable. So why aren’t they more popular?

Part of it might be psychological: a midfielder who gets between the lines with a view to play forward feels like he should probably take advantage of that, and lobbing it sideways for a guy on the same line to run onto doesn’t feel advantageous. Part of it might be physiological: the lateral switches in my tape review came from fullbacks or dropping wingers who turned inside at an angle that gave them a clear view of the far side fullback, while midfielders tended to play their switches facing forward. When you’ve only got a second to pick a pass it’s hard to trust your peripheral vision.

But maybe it’s just that passers aren’t thinking ahead. Switching to the diagonal option feels aggressive but ends with a turnover or backpass. Switching to the lateral option feels too safe but ends with a dangerous two-on-one where the ballcarrier is running into space at a fullback who’s pinned, unable to step to him without risking a throughball that would put the winger in on goal.

My favorite example came in Bayern Munich’s first game against Atlético Madrid, when winger Kingsley Coman dropped to a Lucas Hernández pass up the sideline and wound up curling into midfield, suckering the defense inward while he got a good view of the far third. Coman had plenty of time and space to play a diagonal to Thomas Müller way out on the right wing, where he waited on the touchline, diligently making the field big. But that’s not what Coman did. Instead he laid a short switch in front of the right back Benjamin Pavard, who carried the ball forward unopposed for thirty yards before laying off to Müller. Bayern had managed to isolate the winger one-on-one, just like a diagonal would have. They’d won the race. But they’d done it with two safe, easy passes at a rhythm that gave Müller four runners in the box for a cross.

Unlike a diagonal switch, it ended in a shot. ❧

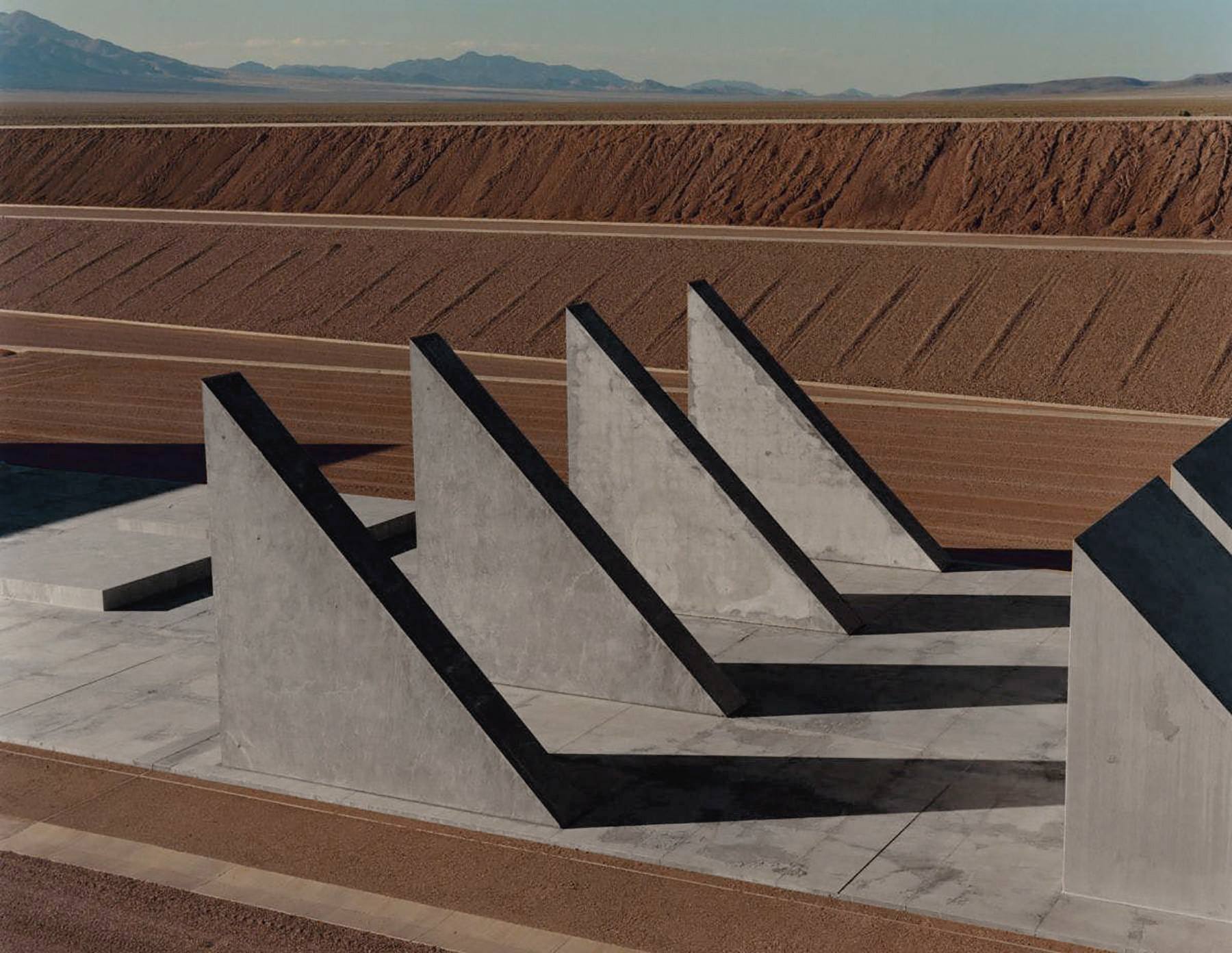

Image: Michael Heizer, City

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.