Welcome back to THE BIG BOOK OF BUILDUPS, space space space’s four-part special on how Champions League teams build out of the back. The first letter and this one are free for all members; parts three and four will be paid letters for socios. If you’d like to get those too, you can subscribe here.

We talked in Day 1 of THE BIG BOOK OF BUILDUPS about how a basic problem the team on the ball has to solve is that most of its bodies are pointed the wrong direction. We looked at rotation as a way to get a player in space with time to receive a pass, turn, and face play. But what if you don’t have time for all those fancy movements and countermovements? What if you’ve got an open passing lane right now and can see a guy wearing the right color shirt at the end of it? Who cares that he’s got a fullback’s coffee breath warming his ear, filling it with sweet promises about what a cleat’s going to do to his Achilles tendon the second he receives the ball. Sometimes you just want to play the pass forward now and sort out medical bills later.

Day 2 is about the ways teams try to combine with players in bad positions to get the ball to a player in a good position: from a guy facing backward to one facing forward, maybe even already moving forward, between the defense’s lines with nobody in the way. If you can make it that far, you’ve already aced the buildup without ever learning how to pronounce juego de posición. And you can, with good passing and movement.

Outside In: The Fullback Scenario

Quite possibly the single most common pass in the buildup is from a center back to the fullback on the same side. The fullback will typically be pushed up a little past the defense’s first line and out wide enough that he can receive facing the field under no immediate pressure. It’s a good spot to try to move the ball further up the field, which is probably why the list of players who do a lot of their team’s progressive passing is heavy on fullbacks, including some usual suspects like Trippier, Hernández, Shaw, and Robertson.

Pressure does eventually reach the fullback, as it gets to us all. Usually it’ll come from an opposing midfielder scrambling out at an angle that prevents the most dangerous next pass, into the heart of the defensive block, but leaves open two tempting lanes: sideways to a defensive midfielder or straight up the sideline. To turn either pass into a successful buildup, though, you’re probably going to need a little movement to go with it.

The Lateral Midfielder

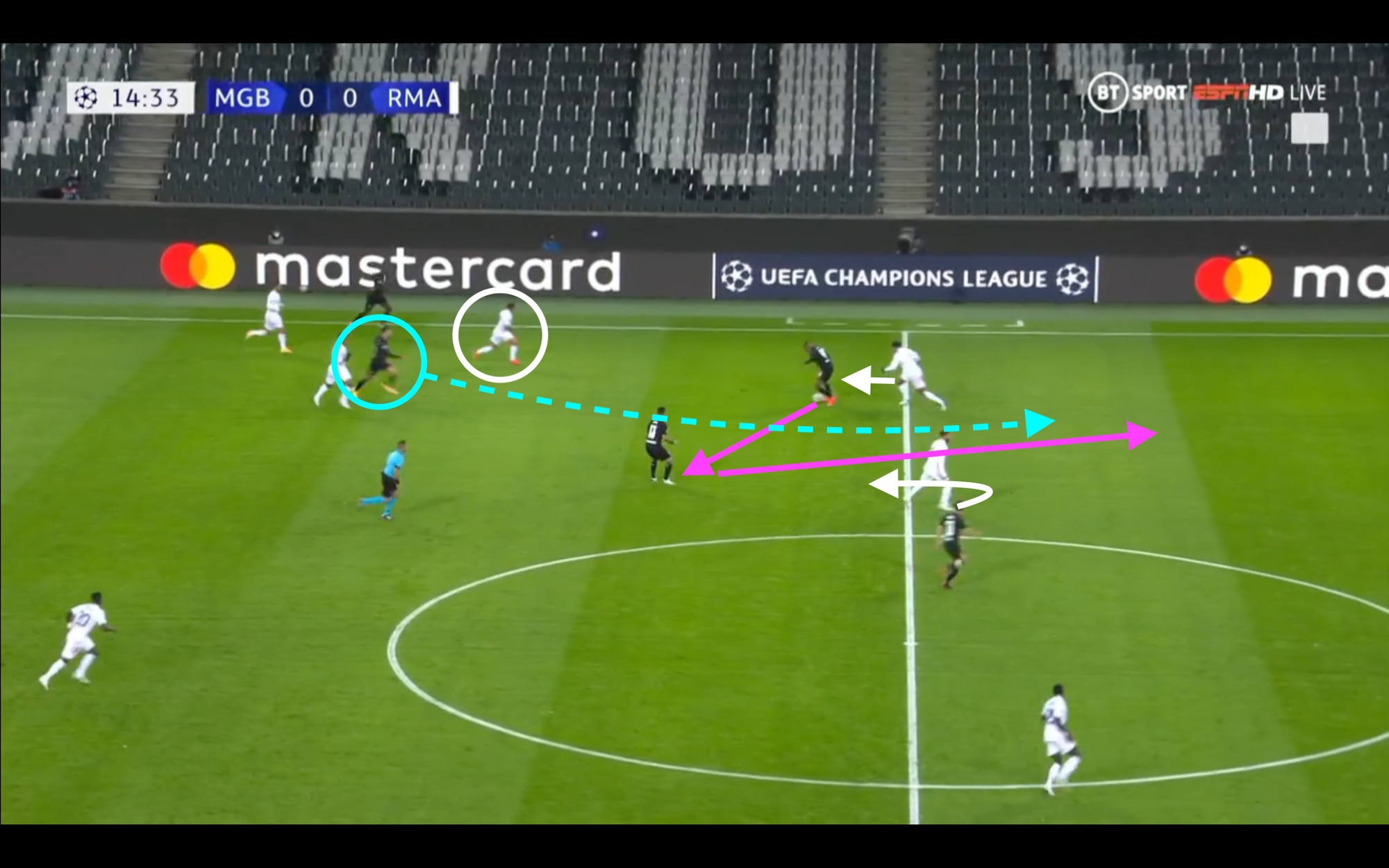

No real magic to this pattern: it’s just a defensive midfielder sidling over to receive a short sideways pass from the fullback, completing a quick outside-in routine that works the ball from the attack's first line to its second by going around the press instead of through it. What makes this boring play work is the threat of something more exciting. In the shot above, it’s a Gladbach winger dragging Toni Kroos upfield so the defensive midfielder can receive undisturbed. Bayern Munich was probably the best at this move in the games I reviewed, which seems kind of insane when you think about the damage Joshua Kimmich can do from the second line—until you compare it to the damage Serge Gnabry and Kingsley Coman can do over the top if you don’t track them. Okay, yeah, let Kimmich have it.

The Underlapping Fullback

Let’s say you’re feeling frisky. Instead of shuffling the ball sideways, you want your fullback to send it straight up the sideline to a winger dropping to the ball. There’s usually enough daylight to squeeze the pass through, but the receiver’s in a tight spot, pressed up against the chalk with a defender at his back. He needs somebody coming toward him who he can dump an easy pass off to. Enter the underlapping fullback.

Again, the idea here isn’t complicated. As soon as the fullback sends the ball up the wing, he takes off running upfield, angled slightly inward so he won’t collide with the winger and will have a good view of the field when he receives the layoff. If the fullback’s lucky, the guy who was pressing him will follow the ball instead of the run. Even if the defender knows exactly what’s coming, it’s tough to stop. The fullback gets to decide when he’s going to pass the ball and burst upfield; his marker can only guess. The fullback is already facing the way he wants to go; his marker has to spin around as he sprints back. It’s pretty easy to for an underlapping fullback to get a step on his marker and receive unmarked; the hard part is controlling the layoff and picking the next pass all while streaking upfield.

Trend alert: this is the go-to move for a lot of elite teams in the buildup right now. The speed, touch, and tactical awareness of the best modern fullbacks is too good to waste on plain vanilla circulation or overlap-and-cross routines in the final third. Bayern and Real Madrid have probably been the most effective underlappers in group stage so far, but a younger generation of fullbacks like Barcelona’s Sergiño Dest practically grew up in the halfspace—we’ll see more of this in the next few years.

For bonus fun, the underlapping fullback can continue his run all the way to the final third. More than a few center backs in my tape review got caught napping when they were stepping to a midfielder or winger while a fullback they hadn’t been keeping tabs on went streaking past them. Madrid’s combination of aggressive pressing and lazy defensive switches made them especially vulnerable, but Lucas Vázquez and Ferland Mendy gave as well as they got.

Inside Out: The Dropping Forward Scenario

Not everyone wants to build up the sideline. Intricate midfield play may not be cool right now but a lot of teams still look disorganize defenses by playing through the channels. Usually it'll be a pass from a center back to a winger or striker dropping to the ball, daring an opponent to leave the back line and chase them. The basic situation for the team in possession is the same as in the fullback scenario: you’ve skipped lines with a vertical pass to a guy who’s most likely about to get his ankles surgically removed, so you’re looking for a short layoff to somebody facing play to keep things moving forward. How exactly the pattern likely to play out depends on how and where he's dropping.

Dropping in the Halfspaces

In theory a forward dropping to a straight-ahead ball from a center back could lay it off in either direction, but in my tape review the outlet pass was almost always out to the fullback. Makes sense, since the threat of a ball inside makes defenses close ranks in a hurry. But if the ball’s just going to wind up with a fullback outside the block, was the initial low-percentage pass up the channel worth the risk? Well, maybe—if you rotate. In the play above, as Pulisic drops to the ball, Reece James has a good view of Kai Havertz sliding behind him for a pass up the wing. The whole buildup takes Chelsea just three passes back to front and ends with Havertz one-on-one on the wing. Simple, clean, effective.

Dropping Centrally

It’s frankly pretty rare in Champions League games between well matched teams to see a pass in the buildup hit a striker dropping straight to the ball—it feels like the rare play that’s simultaneously too risky for the attack and the defense. But if for some reason a channel does open in the middle, it gives the receiver his choice of outer thirds to play into, and he’ll usually draw enough interest that one side or another’s going to be an absolute ghost town. Barcelona sometimes used this kind of linking play instead of a simple switch, probably because their forwards have the touch to pull it off. Still, that’s a pretty dangerous spot to risk miscontrolling it with a defender on your back.

Drop and Roll

Here’s a neat trick that works better if you’re dropping inside instead of on the wing. After you’ve received and dumped off to somebody facing play in an adjacent channel to your left or right, spin the opposite way and be the runner in support for the next pass, when the ball skips up a line. In the play above, for example, Curtis Jones lays off to Trent Alexander-Arnold on the flank then spins inside. He knows three things: first, that Atalanta’s man-oriented defense means his marker will chase him instead of jumping the backpass; second, that this will open a passing lane up the wing to Mo Salah; and third, that he, Curtis Jones, will be running to greet Mo when he's looking for someone to lay off to. By stacking two drop-and-layoff moves on top of each other, Liverpool hits the final third at a jog, facing play, and without taking many risks in the buildup. It’s a lovely play, and it’s built from nothing but the simple tactics we’ve covered here in tennish minutes. Go forth and build like Klopp. ❧

Thanks for reading space space space! I’m going to be real with you guys, these videos take a super long time to edit and animate, so it may take me a few more days to get the third and fourth parts of THE BIG BOOK OF BUILDUPS out, but subscribe here and they’ll be in your inbox shortly. Day 3: Switches! Day 4: Crab Walking! (We’re still workshopping the name of that one.)

Image: Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field (Photo: John Cliett)

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.