In praise of Gyasi Zardes, a striker who didn't score.

One way of thinking about sports is that because winning is the point of the game, and outscoring the other team is how you win, the scoreline is the best and maybe the only real measure of how well you played. A striker did his job if the ball is in the net. The team that scored more goals than it gave up was, by definition, the better team. To quote a traditional American proverb: Scoreboard, motherfucker.

Another, less exciting way of thinking about sports is that playing well means doing things that are likely to help your team win. Shooting a contested jumper is a worse play than passing to an open teammate under the basket, even if the low-percentage shot happens to go in. The wide receiver who ran crisp routes all game for zero yards outplayed the one who couldn’t get open but caught a deflection for the winning touchdown. This kind of fandom is mostly for nerds who can’t experience joy. We’re sorry, we really are.

Anyway, I don’t know if you’ve been paying attention to American soccer lately, but Ricardo Pepi has been scoring a lot. It’s a great story. He’s a talented 18-year-old Mexican-American from El Paso — so close to Ciudad Juárez that even the cellphone towers there aren’t sure which national team you belong to — who just six weeks ago committed to play for the United States. In his first cap last month he scored a goal and assisted another, earning his country three much-needed World Cup qualifying points, then just the other night against Jamaica he bagged a winning brace. European scouts are watching. The hype machine is humming. For a country whose budding golden generation is only missing a center forward, the whole thing feels like destiny.

Joyless nerd that I am, I didn’t think Pepi played all that great in the Jamaica qualifier, and I was drunk enough to say so on the internet. Actually, what I said was “Gyasi Zardes has been better than Ricardo Pepi tonight.” Boring tweet, right? Not if you’re a United States Men’s National Team fan who knows that Pepi is a promising young player who scored two goals, Zardes is an out-of-favor veteran who couldn’t convert some big chances in the second half, and guess what, Mister Smartypants, strikers are supposed to score goals, not miss them. People were pissed.

But let me try to show you what I was looking at. It’s about movement.

Gregg Berhalter’s USMNT usually plays in a 4-3-3 with narrow wingers. In a home game against a weaker opponent where the USMNT controls possession, the fullbacks push up and provide width, like so:

As the attack looks to play from the outside in, the key to breaking down the defense is that little triangle between the near-side center back and the USMNT’s winger and striker, the two accessible options inside the block. The striker needs to be close enough to keep the center back honest when the winger makes a seam run, but he’s also got to be ready to lead the line himself when his wide teammates are looking to get into the box. Neatly timed opposite movements — the winger goes one way, the striker goes another, and the center back is caught in a decision about who to follow — are essential.

Here, watch this sequence from Zardes:

As the ball swings out to the fullback, the winger, Tim Weah, starts a seam run. Zardes stays glued to the ballside Jamaican center back’s shoulder, letting him know that if he tries to follow Weah he’ll be opening a passing option directly into the heart of the defense. The center back can’t leave him until the ball is released up the line, which gives Weah all kinds of room to receive and turn. By the time he does Zardes is dragging the other center back on a near post run and clearing room at the penalty spot for the trailing winger, creating two unobstructed targets for a cross if Weah can just sneak it past his man.

Now compare that to a similar play in the first half. At the moment the pass is played to the fullback, Pepi is flatfooted between the lines, not paying attention. He’s at least five meters off the front line in a non-threatening position when the winger starts the seam run, which frees the center back to start his sprint to close down before the fullback even releases the ball. Even if the pass had been placed somewhere the winger could get to, he wouldn’t have had much time to turn, and even if he had turned his striker wouldn’t have been in the box. Regardless of how well the fullback and winger do their part, the striker’s positioning and movement mean there’s no chance to score on this play:

Pepi’s timing wasn’t always bad. On his second goal, a sort of fast break version of that fullback-to-winger-in-the-seam pattern, he stays onside and fades across the penalty spot to give Brenden Aaronson a target right where he needs it. Sure, it’s not a complicated run — the center backs are hopelessly caught out, leaving Pepi unmarked in the six — but the man did what needed to be done:

If you watched the game you probably remember that Zardes whiffed a comparable chance in the second half. But look how much more work he puts into it:

That’s him dropping to win the ball. He takes off on an angled run in transition to offer Weston McKennie a straight-ahead pass, which forces the right center back to stay narrow and seal off the halfspace instead of getting out to track Weah’s run on the wing. As soon as the ball goes wide, Zardes cuts back inside to get on the left center back’s blind side and drag him away. That gives Weah all the time and space he needs for a cross after beating the first man, but he’s overrun the ball a little bit and has to come back to it with a hard, bouncing pass on his right foot instead of a low roller on his left. Zardes can’t get a leg out for it fast enough.

Make fun of the miss all you want, but that chance doesn’t even happen if Zardes’s initial movement doesn’t help Weah beat his man in the first place. Same basic idea in this clip, where Zardes’s positioning pins the right center back and pulls open a passing lane for Aaronson:

I included two angles on this one because it’s easy to miss a couple key things without the tactics cam replay. First, look at how the right center back is pointing to Zardes and backing up toward him as Aaronson dribbles into the final third. You can see how that opens the passing lane wide. On the standard broadcast that pointing and movement happens offscreen, before the camera pans far enough to show you what the striker is doing. Second, the broadcast angle makes it hard to see that Zardes steps across the center back at the last moment just after the cross is released. If Weah slides the ball to his striker's feet instead of flipping it into the net with the outside of the boot, Zardes is either tapping it in or getting taken out for a penalty. He's done all he can do to maximize his team's chance of scoring.

Point is, it’s really hard to evaluate strikers on TV. A lot of the time you can’t see them onscreen, even when the ball is in the final third, and when you get multiple angles it’s usually to show you the instant the ball arrives in the box, not all the work that went into getting it there. We’re preconditioned to think that center forwards appear out of nowhere on the end of a pass and their job is just to redirect it into the net — or not.

Pepi excelled at the net-related part of his job, Zardes not so much. But this letter isn’t a rehash of the tired old lecture about how finding shots in good spots is a more repeatable skill than finishing those chances. You already know about xG, which means you’ve already thought about sports in terms of probabilities instead of outcomes. The reason I picked clips where Zardes didn’t even touch the ball is to encourage you to think about positioning and movement in the same way, as a probabilistic thing that can be good or bad according to whether it increases or decreases a team’s scoring chances, no matter how the move turns out.

There is, I think, a lot more skill to good striker movement than there is to whether or not a header goes in. This isn't to say that Pepi isn't skilled. He had a few nice moves the other night, he's putting up decent non-penalty xG for FC Dallas, and he's 18 freaking years old, a ridiculous age to be banging in gamewinners for the national team. His movement will get better. If you want to get excited about his development, don't count his goals — watch his runs.

Scoring goals in soccer is good, but goals aren’t the same thing as good soccer. I forget which coach it was who said you wouldn’t just show up to a game in the 90th minute, check the scoreboard, and go home satisfied you knew what you needed to know. From my seat in the stadium at the Jamaica game, I couldn’t see all the slow-motion replays of goals and missed shots that you saw on TV — hell, I’m not even sure I could see the scoreboard — but I could see Zardes’s movement. It looked like good soccer to me. ❧

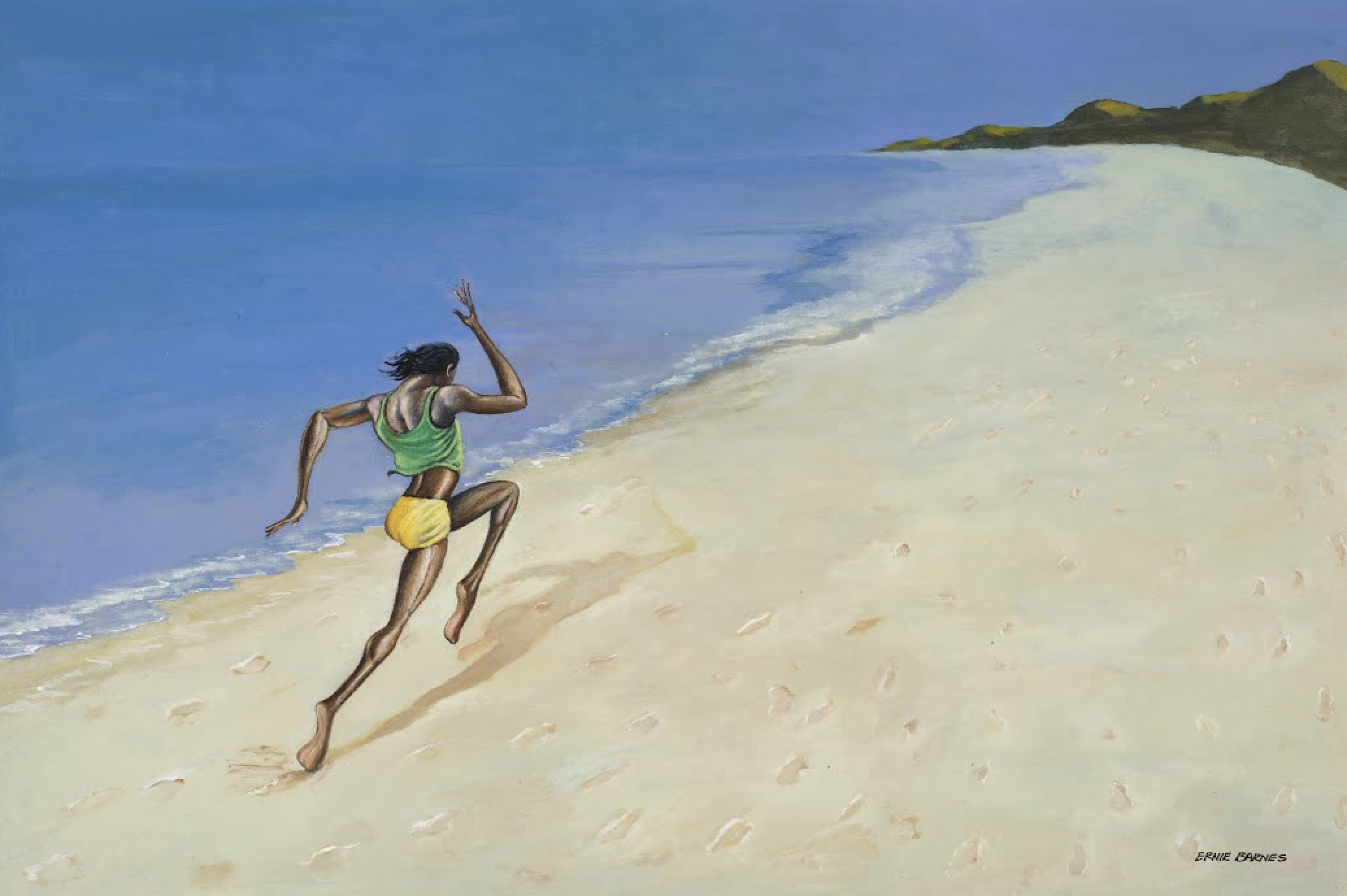

Image: Ernie Barnes, The Beach Runner

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.