Some coaches change shapes to outsmart opponents. Others stick to one system. Who's right?

Y’all remember that time Chelsea beat Man City to win the Champions League? It happened some time during the late Romanov dynasty, I think, back before international soccer moved into our brains for the summer and my own move out of Brooklyn delayed a match review. By now you’ve probably read enough of those, so I want to zoom out a little and talk about the bigger picture.

We all knew the story of the final was going to be whatever weird tactics shit Pep Guardiola tried to pull. Chelsea played pretty much as expected, lining up in Thomas Tuchel’s unbreakable 3-4-3 with César Azpilicueta back on elbow back duty, N’Golo Kanté and Jorginho complementing each other in midfield, and Timo Werner making space for Mason Mount and Kai Havertz between the lines. You knew what was coming, I knew it, Pep definitely knew it. He had weeks to figure out what to do about it.

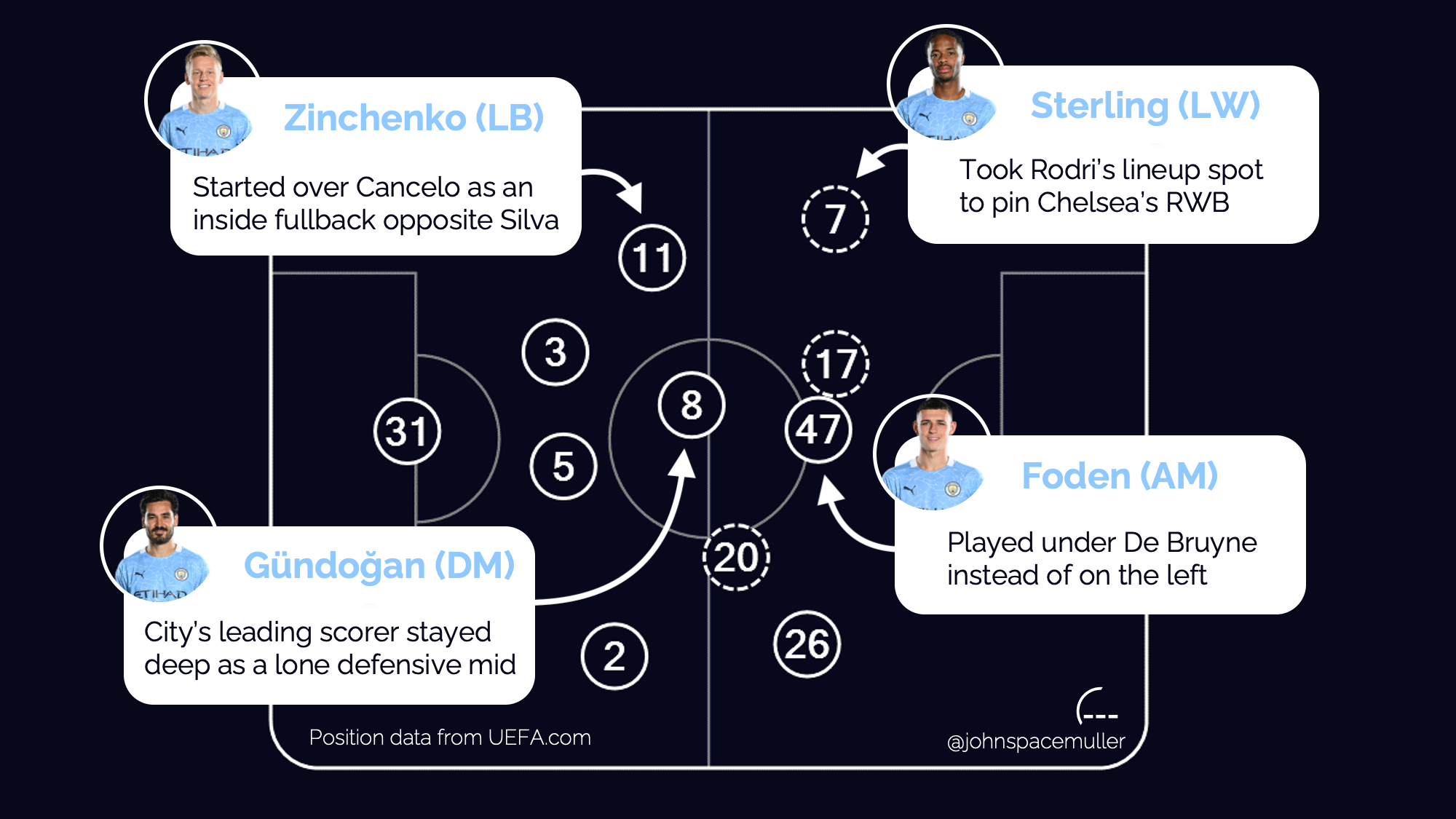

That was a couple weeks too many. In keeping with soccer’s favorite annual tradition, Guardiola led the best team in the world into their biggest game of the season, ripped up the tactics that got them there, and improvised a new and virtuosic way to blow it against a weaker opponent. City played fast when they should have played slow. They played Raheem Sterling at left wing when they should have had Rodri in defensive midfield. Oleksander Zinchenko had been doing a decent job lately as a conventional alternative to João Cancelo at left back, so of course Pep picked Zinchenko to play as a pseudo-attacking mid opposite Bernardo Silva — right where City’s leading scorer, İlkay Gündoğan, should have been. Genius doesn’t owe you an explanation.

Still, City did manage a couple juicy chances early on, and if a few blades of grass had bent their way we’d all be praising Guardiola for his ingenuity right now instead of blaming him for overthinking things. As his former assistant Dome Torrent pointed out before the game, Pep’s supposed fatal flaw is also what makes him great: “In every game he turns things over in his head many times.” Some days he changes the game with asymmetric fullbacks and double false nines, other days he chokes away another Champions League.

There’s an old debate in soccer about how much coaching is too much coaching. On one hand, prepping for opponents is part of the job, and every lineup decision or shape change is an opportunity to exploit some weakness or counter a strength. The head of Italy’s storied coaching academy has said that the game is moving toward “teams who can change system week to week, and even in games, who defend one way and attack in another. The future is teams who can change clothes.”

On the other hand, it’s not like managers are out here sliding pieces around a chess board. Tactics are whatever the guys on the field think they are. Soccer is a fluid, improvisational sport, and keeping players in familiar roles from game to game can help them solve problems they’ve seen before. “Once you start switching formation too much, you can give the impression to the players that it is always your solution,” Tuchel has said. Massimiliano Allegri, who never was big on changing outfits, put it bluntly: “In Italy, the tactics, schemes, they're all bullshit.”

I wanted to know whether managerial overthinking is a real problem, and I figured one final wasn’t going to answer it. This called for data. Are teams better off when they strategically adjust their shape to counter an opponent, or should they take the old Texas Longhorns football coach Darrell Royal’s advice and dance with the one who brung ‘em?

The academic literature is pretty sparse on this one, probably because tactics are tough to measure in any sciencey way. The best stuff most people outside clubs have to work with is starting formation data, gathered by somebody watching a game and jotting down their best guess as to the shape each team is trying to play. It’s a subjective job and there’s not really a predefined set of answers — one man’s 4-4-2 could be another man’s 4-2-2-1-1, etc. Even if the starting formations are accurate, they won’t tell you a ton about in-game tactics like, say, pushing Zinchenko up as an auxiliary attacking mid in possession. We barely even have a language to talk about how teams change their shapes and movements by phase, let alone to fit it in a spreadsheet. But hey, we work with what we’ve got.

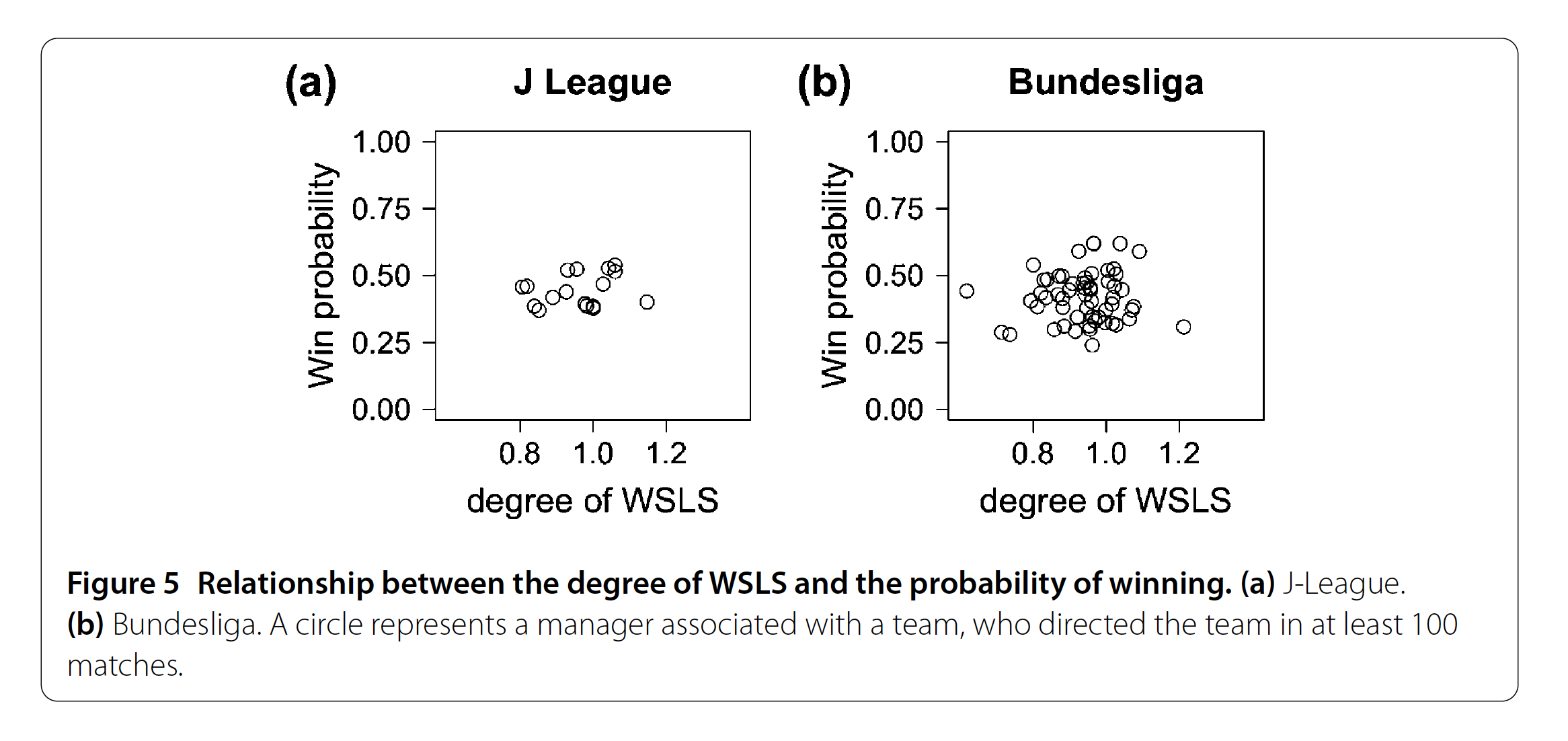

The German website Kicker has been recording Bundesliga formations all the way back to the sixties, and in 2015 some researchers combined that with some J-League data to show that managers tend to follow what’s called a “win-stay, lose-shift” pattern: when things are humming along and the team’s picking up points, they’ll stick with the formation that’s working, but after a loss they’ll try something new. It sounds commonsense enough, but there could also be a little superstition to it, like athletes who won’t change their socks during a winning streak. As best the researchers could tell, changing formations after losing didn’t significantly improve the chances of winning the next game, and it didn’t seem to make much difference to a team’s overall success whether or not their manager was a big win-stay, lose-shift believer. Like most attempts to measure coaching effects, the findings were a big ol’ shrug.

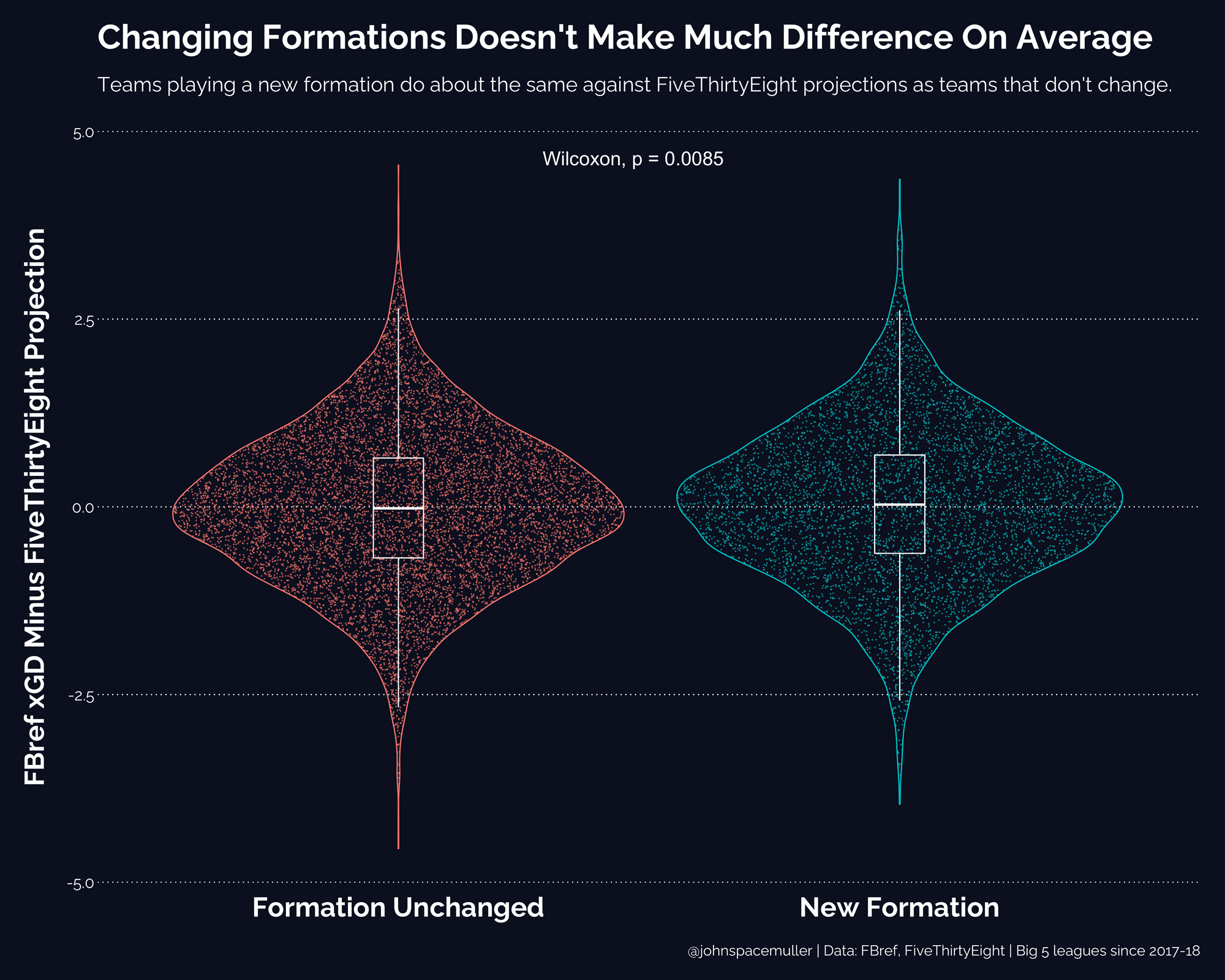

I realized I could try some stuff along the same lines with the Statsbomb formation data that’s freely available for Europe’s top five leagues on FBref. The authors of the 2015 paper measured how formations did in terms of wins, draws, and losses, but with Statsbomb data I could use expected goals for a less noisy performance metric. And where the paper tried to control for historical team strengths using win percentage, I could use FiveThirtyEight’s pregame score projections for a better baseline. If coaches were helping or hurting their teams by changing formations from game to game, the difference between predicted and actual expected goals should be a pretty delicate way to pick it up.

Sure enough, modern European managers seem to subscribe to the win-stay, lose-shift strategy. On average, teams that changed their broad formation (to smooth out granular differences in notation, I grouped Statsbomb’s 48 formations into seven of the most common ones so that, for example, a 4-1-2-3 became 4-3-3) had lost their last game by a goal difference of -0.3, while teams that kept the same general shape had won the previous one by 0.2. (The 2015 paper found that the result two games ago mattered, too, but I didn’t look that far back.)

Whether or not they changed formations, the differences between the two groups shrank back toward zero in the following game. When I compared expected goals to projected goals to control for team strength and conditions, the gap between teams that changed shapes and teams that didn’t disappeared almost entirely. I reached out to my real-life scientist friend Eliot McKinley to ask if any of this meant anything. With about 15,000 games in the sample, it was possible to pick up a statistically significant difference between the groups — tactical changes help! coaches matter! — but the effect size was tiny, about 0.04 goals per game. Maybe some adjustments are better than others, or certain coaches are better at making them, but in the aggregate changing formations appears to make very little difference.

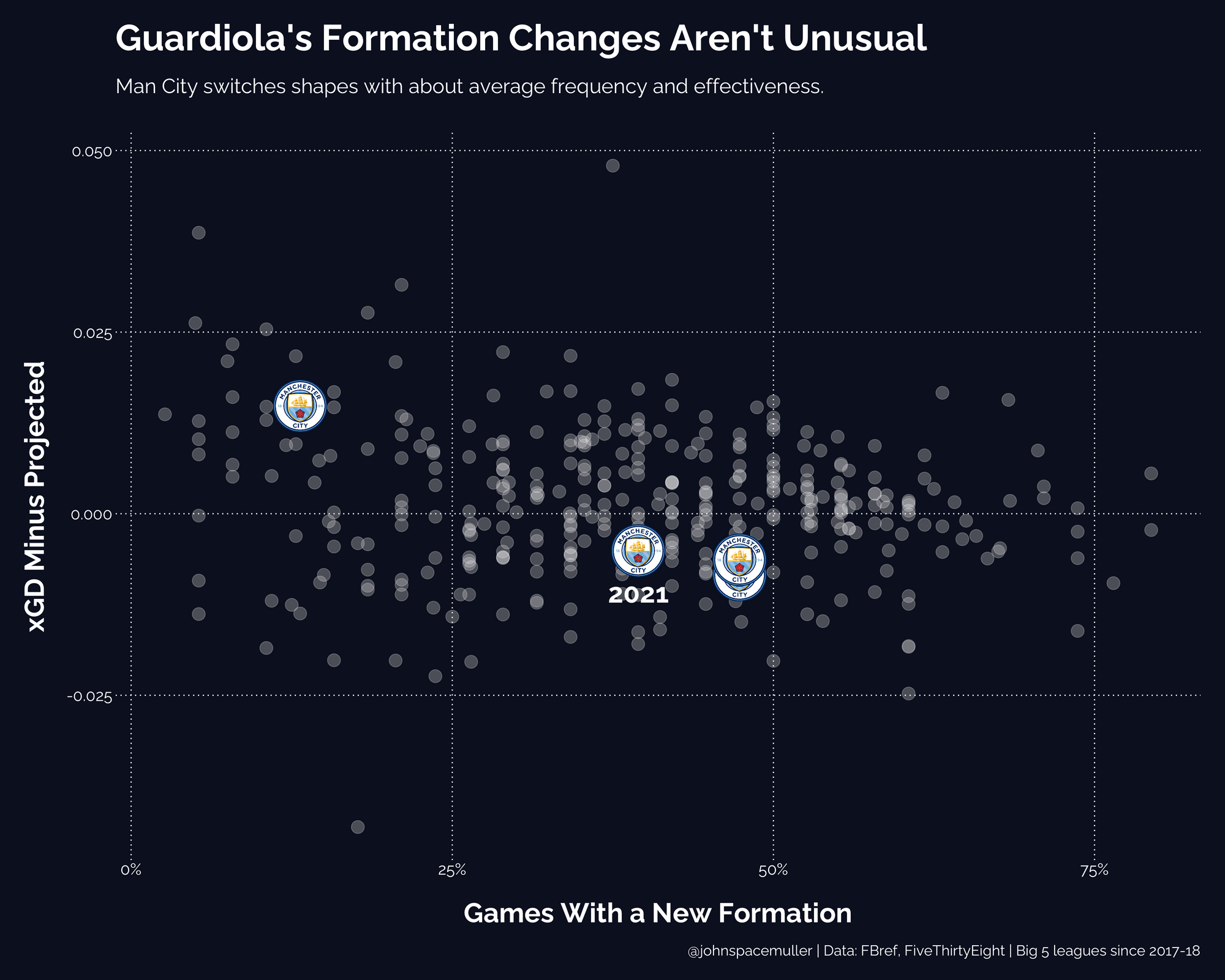

Which, okay, averages are one thing, but what about our best and brightest, one Josep Guardiola? Does his constant tinkering make Man City better, or is it true that he tends to overthink things? Surprisingly enough, City doesn’t really stand out one way or another for either the frequency or effectiveness of their shape changes. Over the last four seasons, they’ve changed their broad formation about once every three games, a typical rate, and performed roughly in line with FiveThirtyEight projections whether or not they were playing a new shape. If Pep’s tactical adjustments make City better — and the arc of the English champions’ season from an clunky double pivot in the fall to a graceful shapeshifter by spring makes a pretty compelling case that they do — then it seems to happen gradually, over weeks or months, rather than through single-match opponent prep.

Of course, once you drill down a particular team and season, you’re probably better off analyzing the games than looking at the formation notation Guardiola has called “nothing but telephone numbers.” City played very differently in the Champions League final than in the first leg of the semi against Paris St. Germain, but Statsbomb classifies their starting formation in both cases as a 4-3-3. Formation data is a blunt tool that can only really tell us anything, if at all, over lots and lots of matches.

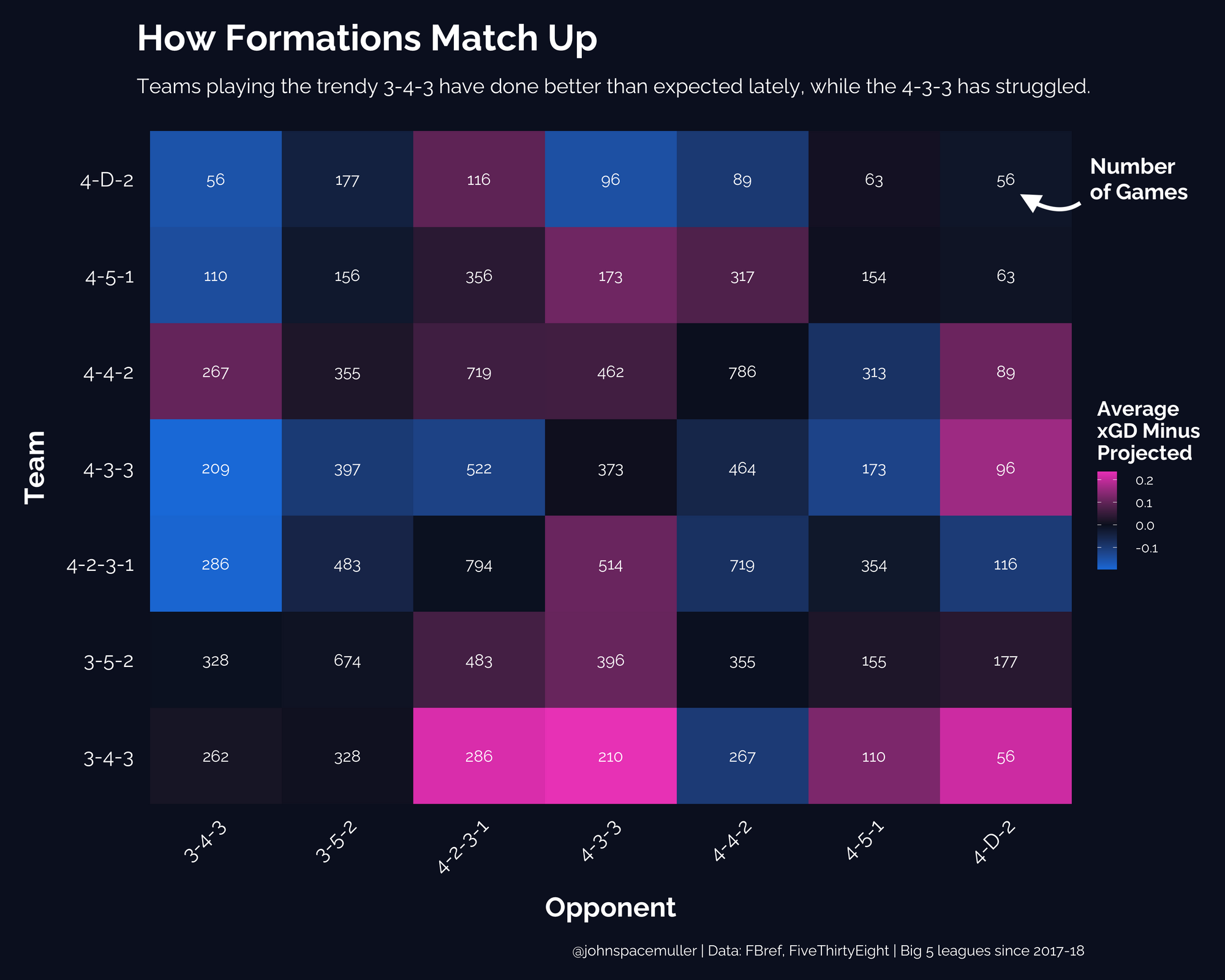

But if you’ve got lots and lots of matches sitting right there on your laptop, it’s hard to resist trying to torture some grand truths out of them. I was still wondering whether certain tactical changes might be more helpful than others, and got curious what the data could tell us about how formations match up with each other. This is the kind of stuff tactics theory nerds argue about all the time, but those conversations are never particularly persuasive in the abstract; formation data may not be very persuasive either, but it’s at least sort of grounded in fact.

I probably wouldn’t read too much into this chart, given all the caveats above, but it’s hard not to notice that the trendiest formation family among Europe’s elite, the Chelsea-style 3-4-3 that everybody seems to be experimenting with lately, is also the one that’s beaten FiveThirtyEight projections by the most over the last four seasons. The shape that seems to struggle the most, especially against a 3-4-3, is the increasingly passé 4-3-3 that Guardiola switched to for the final after playing a 4-2-3-1 and 3-5-2 in his last two matchups against Tuchel’s Chelsea.

No, this grid doesn’t contain the deepest mysteries of the soccer universe, and it probably wouldn’t be a great way to pick your approach for a do-or-die game. But then again, maybe even our smartest coaches don’t actually have a better way than good old-fashioned trial and error. Maybe Allegri’s right and all those systems, all that theory, none of it really means that much. When the whistle blows, soccer belongs to those who play it. ❧

Further reading:

- Kohei Tamura and Naoki Masudadf, Win-stay lose-shift strategy in formation changes in football (EPJ Data Science 2015)

- Brian Phillips, Manchester City Played Pep Roulette and Lost the Champions League (The Ringer)

- Michael Cox, Long balls, targeting the left and a back five – how Chelsea won the Champions League final (The Athletic)

Image: Jesús Rafael Soto, Sin título

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.