Keeping your head on a swivel isn't just about evading pressure. It's about mapping out space.

A few years ago, on a trip to Barcelona, I wandered into a UEFA Youth League game between Barça’s teenagers and Atlético Madrid’s. I didn’t know any of the players — even in a prestigious U-19 tournament, not many were likely to make it big as pros — but one fluffy little midfielder stood out. There was something in the way he always knew where to be, which way to turn, which pass to play, that looked expert, like he was cruising through a video game he’d already beaten a couple times. I thought of Andrés Iniesta, who I’d watched earlier that week, and imagined a shadowy society of Catalan midfielders passing soccer’s secret map from generation to generation while everyone else fumbled around in the dark.

Of course there’s no real mystery to it. Here’s Xavi explaining in an old Guardian interview how this newsletter got its name:

Think quickly, look for spaces. That's what I do: look for spaces. All day. I'm always looking. All day, all day. [Xavi starts gesturing as if he is looking around, swinging his head]. Here? No. There? No. People who haven't played don't always realise how hard that is. Space, space, space.

Soccer is about space. Good players find it. Great players just seem to know where it will be all the time, even before they get on the ball, sometimes even before the space exists. How do they accomplish this superhuman feat? Well, basically, they turn their head and look around.

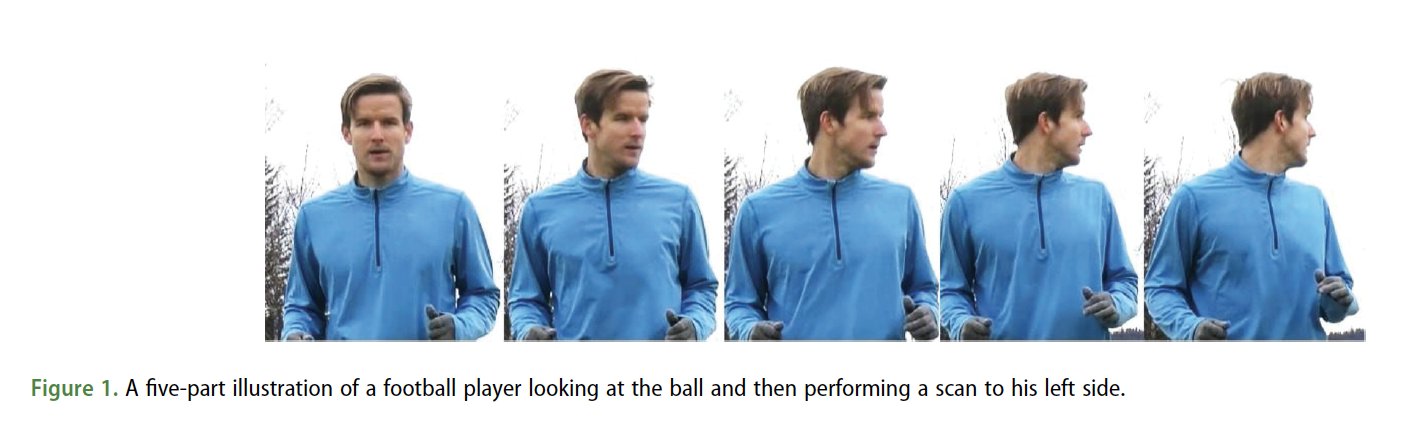

Scanning, also known as checking your shoulder, is an important way that soccer players stay aware of their surroundings. These guys spend most of their time paying attention to what’s happening around the ball so they can be first to react to it. That’s fine, that’s smart. But the game is still going on beside or behind them, too, away from the ball, in other parts of the field that may matter soon. Kids are taught from a young age to “scan” by finding moments to swing their head quickly to one side or the other, take in as much of the pitch as possible, and then snap their attention back to the ball before they miss anything.

Think about this in terms of simple soccer math: the human visual field is about 60 degrees on either side of wherever you’re looking, including peripheral vision. But the average quick pass is played after turning across the body at about 120 degrees. If you want to know what’s happening behind you, in the area you’re most likely to pass to, checking your shoulder isn’t an option, it’s a physical necessity.

Looks easy, right? But even at the top of the game, players can set themselves apart by being disciplined about shoulder checks. In 2013, a team led by the Norwegian sports science and psychology professor Geir Jordet found that Premier League midfielders who scanned right before receiving the ball were more likely to complete a forward pass. Out of the 118 players in the paper’s sample, the two most frequent scanners were Frank Lampard and Steven Gerrard, two of the best midfielders in England at the time.

A new paper out this month, coauthored by Jordet, found that a group of elite U-19s at the kiddie version of the Euros scanned more than their U-17 counterparts. Even at those ages, more scanning was linked to more successful passing, and central midfielders, in the heart of the action, did more of it than anyone. Young players seem to get better at scanning as they grow — or maybe those who don’t do it well enough simply fall behind.

The name of the tiny midfielder who impressed me that day at Barcelona's youth game, I found out through some quick first-half googling, was Riqui Puig. For a couple years afterward it looked like he might develop into the next great center mid to come out of the club’s academy, but this season he lost his spot to an even younger midfielder who didn’t train at La Masia but plays like he did. Pedri, the new starter, is smart and technical like Puig, but with less languid artistry and more economy to his game. Coaches love him. At 18 he’s already written in ink on every Barça team sheet, and this week he became the youngest player ever to play for Spain at the Euros.

How did Pedri get so good so fast? I think it starts with his scanning.

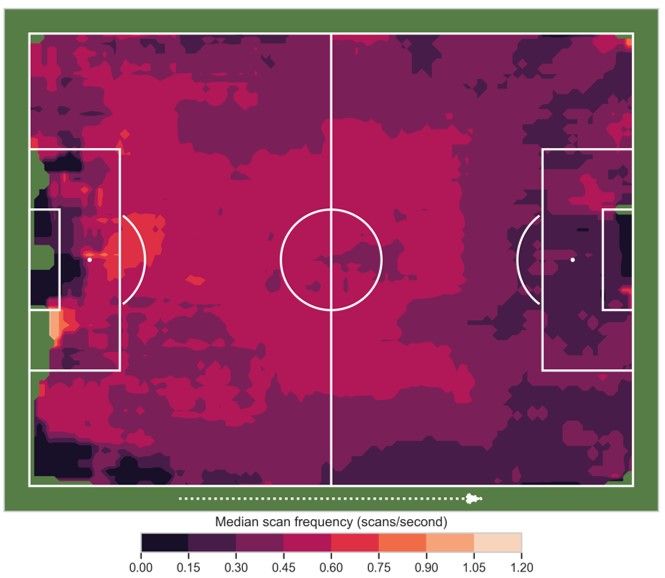

I’ve been going over his performance against Sweden in the first round of the Euros practically frame by frame this week, studying when and why he looks around. What’s impressive about Pedri's scanning isn’t how often he does it, at least not in this one game. Back in Barcelona, he plays between the opponent’s defensive lines, in the hairiest part of the pitch, where he needs Exorcist vision to keep track of pressure from all angles. But Spain’s positional play brings Pedri deeper and wider, where he has fewer threats at his back and doesn’t have to swing his head around as much. That jibes with Jordet’s scanning research, which has found that players check their shoulder most often at the top of the defensive box and in midfield, tapering off out in the wide areas.

Instead of sheer frequency, the impressive part about Pedri’s scanning is how disciplined it is. Spain’s rotations in possession follow a well-drilled pattern. When the ball is over on the right, away from Pedri’s side, he’ll push into the center of the attack. But if the attack can’t find a way through on one side, they’ll patiently swing it back around to probe the other side of the defense. That’s Pedri’s cue to backpedal all the way out to the fullback pocket. At the same time Jordi Alba, the left back, pushes up to where a winger would usually be and the actual left winger, Dani Olmo, tucks into the halfspace. That forces defenders to switch assignments and puts everyone in their best position for the last phase of play, breaking down the defense.

Rather than play between the lines with his back to goal in this situation, Pedri gets on the ball deep and wide, facing play, with an important choice to make: zip the quick outlet pass up the wing to Alba, break lines to Olmo or the center forward, or carry it forward into space to attract defenders and try to shake things up. This variable pattern, which Spain repeated approximately nine zillion times against Sweden’s low block, is low pressure but high stakes, a test of Pedri’s decisionmaking more than his technique in tight spaces.

Interestingly, Jordet’s scanning research suggests that looser-pressure situations like this are when players scan the most, rather than when they have a defender on their back. Maybe that’s because guys with room to breathe are most likely to try something adventurous instead of a short, safe pass. As the former La Masia coach Albert Puig tweeted the other day, a player who’s not under pressure should scan first for a chance to break lines, then only afterward to nearer defenders and teammates. Sure enough, Pedri finished the first round of Euro group stage games second only to Toni Kroos for progressive passes, and tied with him for passes into the final third. Not bad company for a teenager on the international stage.

There are two specific moments in Spain’s circulation pattern when Pedri will check his left shoulder almost every time. The first is when somebody on the far side passes back to the right center back and Pedri starts his reverse-gear jog to where he expects to receive the ball two passes later. This check is all about positioning: Is Alba high enough for them to execute the rotation? How far should Pedri back up so that his angle to turn and pass to Alba — always his first look — will be a smooth, standard 120 degrees?

Then there’s the second check, the one about decisionmaking. If he makes it back to the pocket with a second to spare, Pedri will scan left again, quicker this time, before receiving the ball. This check seems to be for sizing up the nearest defender, the right midfielder on the corner of the defense’s 4-4-2 block. If the defender tucks inside to deny a linebreaking pass to Olmo, Pedri knows there’s room to push the tempo to Alba up the wing. But if the defender cheats out toward Alba, Pedri can play the incisive pass to Olmo or dribble in toward the heart of the defense. The play is a classic college football option read, except the quarterback is a scrawny high schooler from the Grand Canary Islands who's never taken a snap.

The thing that makes Pedri’s scanning effective is that it isn’t about evading pressure — it’s about systematically mapping out space, Xavi style. One check for positioning, a second for decisionmaking, every time. By locating just the right spot to be in, identifying what his teammates and the nearest defenders are doing, and making his shoulder checks a natural, habitual part of his movement each time he changes direction, Pedri can make his mind up about which way he’ll take the play before he even receives the ball. That gives him a split-second head start on the defense. Sometimes, when the dominoes fall right, that’s all it takes.

Against Sweden it never quite happened, but Pedri wasn’t discouraged. “We played well last night, created many chances. If we keep going like this we’ll do well,” he said after Spain’s first game ended in a slightly unlucky scoreless draw. Who could argue with this kid stepping up to the mic to speak for his whole country? He’s got vision, this one, a talent for peeking into the future. ❧

Further reading:

- Geir Jordet et al., Scanning, Contextual Factors, and Association With Performance in English Premier League Footballers: An Investigation Across a Season (Frontiers in Psychology 2020)

- Karl Marius Aksum et al., Scanning activity in elite youth football players (Journal of Sports Sciences 2021)

- Geir Jordet, Why scanning is about more than just frequency (Training Ground Guru)

- Sid Lowe, I'm a romantic, says Xavi, heartbeat of Barcelona and Spain (The Guardian)

Image: Alan Rath, Watcher VIII

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.