Manchester City’s defensive midfield pair is the latest development in a quarter-century-old tactical argument between friends.

There was a touch of defeat in Manchester City’s first win of the season. You could see it in the hollows under Pep Guardiola’s eyes. “I’m incredibly happy,” the coach told a reporter who used his presser question just to check if everything was okay. He stared glumly into the middle distance like an Antonioni actress. “I don’t have a nice smile, that’s all.”

Maybe he’s still drinking away the fresh hurt of another Champions League collapse, but Guardiola’s eyes looked deader than that, suggesting the emptiness of a man who’s come face to face with his own limitations, the resignation of an artist whose rent is overdue. It was the stare of a billion-dollar manager who’d just started a 35-year-old Fernandinho in a double pivot.

As a player, Pep hated a flat defensive midfield pair. “It reduced his space on the field, kept him from directing the team’s play like he wanted, limited how he positioned himself, and, above all, broke his fundamental principle as a player: calculating the next pass before receiving the ball,” his biographer Martí Perarnau wrote. “In the double pivot, Guardiola felt lost and strangled.”

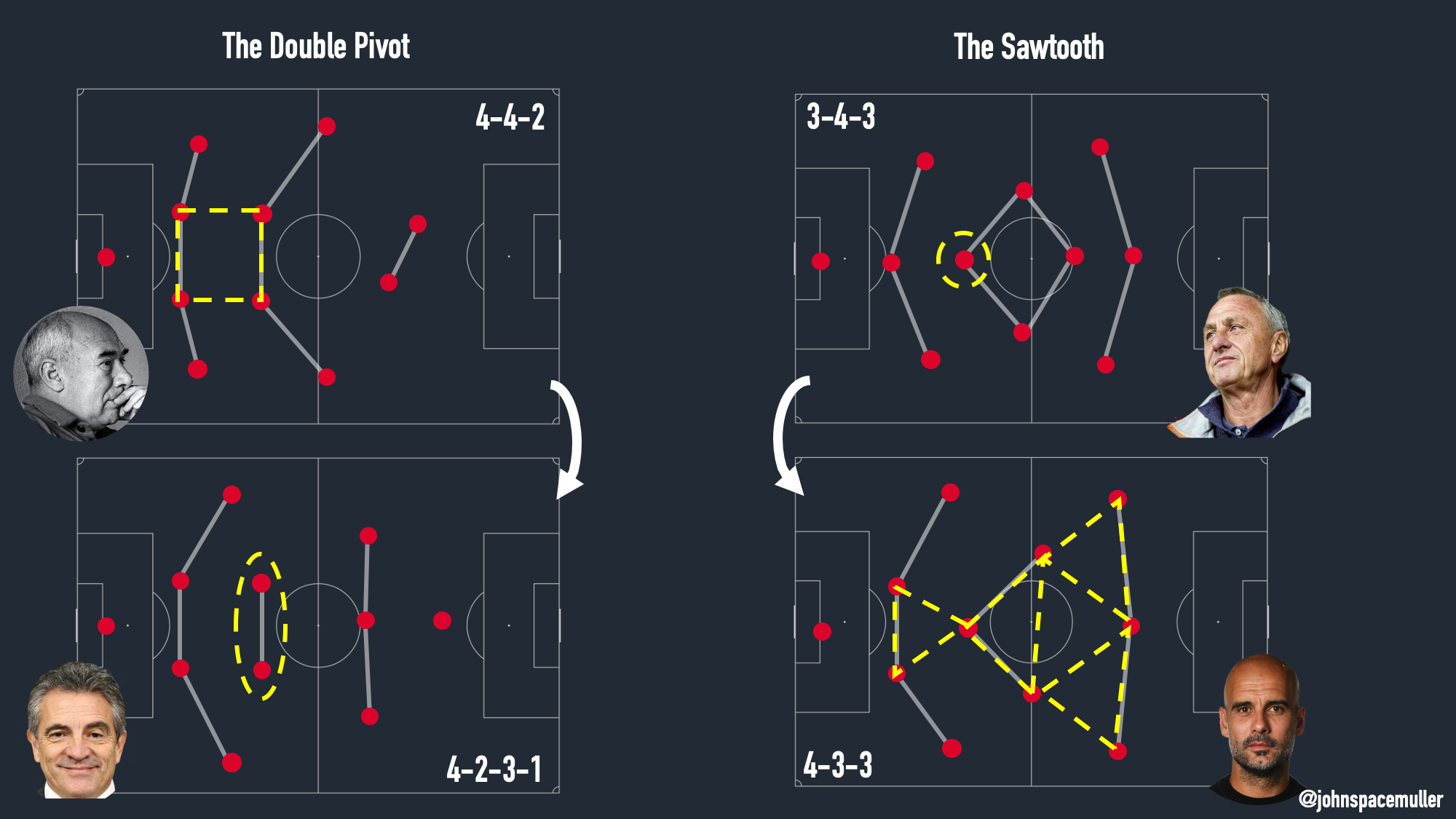

Pep had been brought up in Johan Cruyff’s diamond 3-4-3, whose geometry optimized angles in possession so that every player would receive on the half-turn with forking options to play forward. But the dominant formation in the nineties was still the sturdy 4-4-2, whose central midfield duo protected the back line while the attack traced direct paths through the wingers and striker pair. One shape was built around passing triangles, the other around defensive lines. One created space, the other denied it and took what it was given.

The Battle of the Wunderkinds

Synthesis of sorts came from a man named Juan Manuel Lillo, who took over Real Oviedo in 1996 at the Nagelsmannesque age of 29 to become the youngest manager in the history of La Liga. In the decade since the 1986 World Cup, teams had increasingly reserved their second striker spot for a free-floating playmaker. Lillo formalized this role and pushed the 4-4-2’s wide midfielders up alongside to make the shape we now know as a 4-2-3-1. By the standards of the time, it was an attacking innovation. “My intention was to pressure and to try to steal the ball high up the pitch,” Lillo explained. “It was the most symmetrical way I could find of playing with four forwards.”

Lillo’s formation turned his center mids into a true double pivot, the rear vertices of twin passing triangles in the midfield five. But they sat directly in front of the center backs in a defensive box that created redundancies and awkward right angles in possession. Although Lillo had found an elegant way to fit four attackers on the pitch, they were still outnumbered by a back six unless a midfielder got forward or a fullback overlapped. The 4-2-3-1 was more fluid than the 4-4-2, but it made some sacrifices to preserve its predecessor’s defensive solidity.

After a match where Lillo’s Oviedo fought Cruyff’s Barcelona to a draw, Guardiola sought out the opposing coach, determined to understand the “something special” he’d seen happening on the field. A two-man mutual admiration society was born. But the friends’ years of talking tactics didn’t change Pep’s mind about the problems with the double pivot. When he started his own managerial career, Guardiola arranged Barcelona in a 4-3-3 that Lillo referred to as “the sawtooth, creating triangles so that the pass from the center mid always finds a straight line that goes deeper into the defensive area.” Commentators hailed Barça’s passing triangles from a back four as the next evolution of “modern football.” Yet it was Lillo’s 4-2-3-1, not Guardiola’s 4-3-3, that was busy taking over the world. “They try to disguise it,” Lillo said in 2004, “but almost everyone plays this way now.”

And so it’s gone for the last decade or so. The global elite, the clubs with the money and ambition to play “modern football,” sent two midfielders forward in a 4-3-3 to make pretty passing triangles and press on the front foot. For everyone else, well, there was always the trusty double pivot. The 4-2-3-1 became soccer’s workmanlike default, suited to a new generation of inverted wingers and attacking fullbacks. A few sides, like José Mourinho’s Real Madrid and Jupp Heyncke’s Bayern Munich, played two defensive midfielders at the game’s highest levels, but for the most part the managers of the world’s most elegant teams—Guardiola, latter-day Jürgen Klopp, peak Maurizio Sarri, even (gulp) Zinedine Zidane—preferred a single pivot.

That didn’t mean the defensive midfielder was always alone. Coaches have always found ways to reinforce their second line when the game called for it. Xavi would drop near Sergio Busquets in Barcelona’s buildup. Phillip Lahm would tuck inside from a fullback spot to distribute and defend in Bayern’s midfield. But these were dynamic occupations, tailored to the opponent and phase of play. “The formation moves because it doesn’t exist. It’s the mentality of the players that makes tactics,” Guardiola said at Barcelona. “We don’t play a double pivot because Xavi and Busquets don’t play at the same height. But the formation is a lie because people move, and we sometimes have a defense of three and other times four.”

The Double Pivot Glows Up

Formations are a lie, a simplification, and yet the shift toward a double pivot at top clubs right now still feels like it means … something. Hansi Flick’s Bayern Munich romped through the Champions League in a 4-2-3-1 that played not just dominant but beautiful possession soccer. Thiago’s move to Liverpool may yet wind up bringing something similar to Klopp’s midfield. In Barcelona, Ronald Koeman is determined to break with Cruyffian dogma and play an aging Busquets alongside Frenkie de Jong. Real Madrid started the season with Toni Kroos and Luka Modrić behind Martin Ødegaard. Andrea Pirlo’s Juventus paired Weston McKennie with Adrien Rabiot in front of an Italian-style back three. Sure, it’s the start of the season and everyone’s still feeling things out, but right now it looks possible that Thomas Tuchel’s PSG might wind up the last superclub not playing a double pivot.

Even Guardiola hasn’t been immune. Eight times in last season’s Premier League City lined up in a 4-2-3-1, usually against an opponent in the top six. Two years ago, in the 100-point season, they’d done it just twice. But that was back when City’s press was unbreakable and their center backs could be more or less trusted to clean up. As his team’s transitions have gotten creakier, Pep’s been pragmatic about occasionally switching to an old school boxy back four to protect his goal. As long as one of the rear midfielders was a passer who could bump up a line, an Ilkay Gündogan or David Silva or sometimes even Kevin de Bruyne, Guardiola still had his principles.

But are those principles changing? In June, when Mikel Arteta left for Arsenal, Pep called up his old friend Juanma Lillo to become his new assistant. A few weeks later, City lined up in Lillo’s beloved 4-2-3-1 against Liverpool—not the first time Guardiola’s side had tried it, but certainly the first time they came away 4-0 winners. Maybe there’s still something to Lillo’s original vision of the formation as an attacking one, a way to reconcile a defensive mid pair with Guardiola’s sawtooth modern football. If there is, it’ll pretty much have to mean borrowing from new-model 4-2-3-1s like Flick’s Bayern and Erik ten Hag’s Ajax to make the double pivot more dynamic, less limiting, to keep Guardiola’s midfield from feeling lost and strangled.

How Pep Fixed Wolves

City’s first win wasn’t all bad, no matter what Pep’s face said. A Rodri-Fernandinho midfield pair was never going to be sexy, but with Gündogan unavailable and Silva departed Guardiola had to try something different than his double pivots that lost to Wolves twice last season. The question was whether his defensive-minded duo could do more than protect debutant center back Nathan Aké—whether, if you want to go all big picture about it, Pep and Juanma could put their heads together to come up with a stylistic fusion on the second line.

As far as your standard-issue tactical theory goes, a double pivot didn’t really make a whole lot of sense against Wolves’ 5-3-2. Nuno Espírito Santo’s striker pair pressed one on one against Aké and John Stones, cutting off their straight lanes to the boxed-in defensive midfielders. Wolves’ midfield three shifted side to side to trap City’s fullbacks against the sideline while conservative wingbacks in Nuno’s back five blocked the way forward. There were plenty of times when Fernandino and Rodri stepped on each other’s toes or had to improvise angles to break the double pivot’s natural redundancy, but the best moments came when they stretched themselves into more useful shapes while clinging to what Pep would call the mentality of the double pivot: no matter where one went, the other stayed anchored in front of the back line.

That meant the defensive box could become a more fluid diamond in the buildup when one midfielder dropped between the center backs and the other came central, or Rodri could sidle over to the left back spot and free Mendy up the wing. When he did, the fullback had the option of hugging the touchline or coming into the halfspace to draw attention and open space for a winger to get in behind. But maybe the most important knock-on effect of the inverted midfield triangle was to grant Kevin de Bruyne total freedom as a central attacking midfielder. He roamed between the lines and popped out on either side of Wolves’ middle three, creating 0.4 non-penalty expected goals, 0.4 more expected assists, and drawing a penalty that he converted himself. Turns out having a forward midfield partner was only cramping KDB’s style.

Defensively, well, having two defensive midfielders helps. Wolves didn’t get up the middle much in transition. City’s soft underbelly was safe. Like it did in possession, the double pivot looked best off the ball when it was more a mentality than a position, like when a defensive midfielder could commit himself fully to getting over to cut off an attack up the wing, knowing his partner would shift over to hold down the middle. Even when Wolves started to break open the game in the second half, it wasn’t so much a Rodri and Fernandinho problem as it was a Benjamin Mendy hasn’t been himself in years and Adama Traoré is a mismatch for everyone problem. That said, if City had another advanced midfielder to press defenders and block passing lanes alongside Kevin de Bruyne, some of those Wolves attacks wouldn’t have developed in the first place.

The double pivot worked. It got the win. True, it worked best when it looked least like a 4-2-3-1, but that’s more or less how the modern double pivot goes. And yet it just wasn’t City, you know? Pep’s bottom-heavy formation with four up front had to attack fast, without its usual control, counting on the individual quality of the attackers to overcome Wolves’ numerical superiority in the attacking third instead of working the ball into the opposition half and strangling them to death with patterned movement. Last season Manchester City led Europe in its share of pressures in the attacking third, touches in the attacking third, and touches in the penalty box. A season of playing the way City did against Wolves would have put them midtable for attacking third pressures (23%), just above Crystal Palace for attacking third touches (25%), and dead last in the Premier League for action in the box (3%).

We know it’s possible to play controlled attacking soccer in a double pivot (just ask Schalke how last week’s date with Bayern went). Juanma Lillo’s defensive midfield pair doesn’t have to be old fashioned or workmanlike. But if that’s where City’s headed, Pep’s got a lot of work to do in midfield before he can find his smile. ❧

Thanks for reading space space space! Please consider supporting the project by becoming a paid subscriber—we'll have our first premium post next week.

Further reading:

- David Garcia, What If Success Looked a Lot Like Failure? The Story of Juanma Lillo (These Football Times)

- Jonathan Wilson, The Question: why has 4-4-2 been superseded by 4-2-3-1? (The Guardian)

- Pablo Molina, La trigonometría 'guardiolana' según Juanma Lillo (Libertad)

- José A. Espina, "Ahora lo disfrazan, pero casi todos juegan así" (AS)

- Sam Lee, City hope Lillo keeping Pep on his toes will also keep him in Manchester (The Athletic)

Image: Michelangelo Antonioni, L'avventura

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.