Tonight's South American final will come down to one man. No, not Messi or Neymar. The guy in between.

There are few funnier things in sports than reading down a Brazil tournament teamsheet stuffed with famous, lavish-sounding Portuguese names — Neymar Jr., Gabriel Jesus, Lucas Paquetá, Marquinhos, Thiago Silva — and then, stuck in the middle like a fly in soup, like a printer’s error left over from running a Lancashire Sunday league lineup last week: Fred. Gets me every time, man.

A Seleção has had other Freds before, but none that could match this Fred for raw Fredness per 90’. The name just suits him. In a team of prancing thoroughbreds, the Manchester United defensive midfielder is a workhorse, stomping around the pitch doing the dull stuff. He knows he’s not who you tuned in to see. “My role is primarily to protect the midfield, to give the attackers more freedom. Here in the national team, Neymar, for example, Richarlison, Paquetá, Everton Ribeiro,” Fred told Net Diario. “I defend from box to box to free them up and, with quality in the buildup, I get the ball forward cleanly so they can play.”

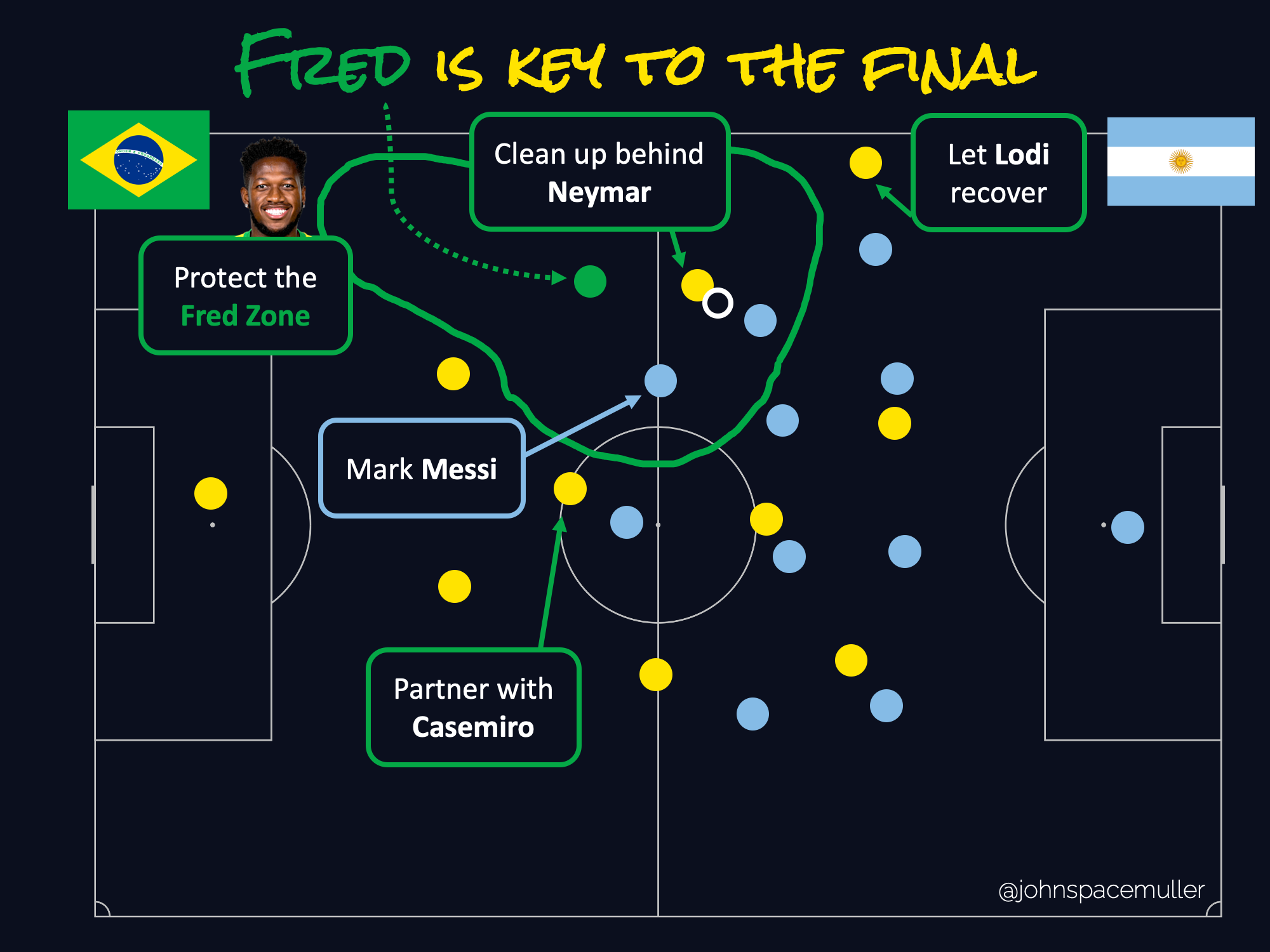

On Saturday night, whether he likes it or not, Fred will be in the spotlight. Well not in it, exactly, but hovering around the edges, like an extra who missed his stage exit and got caught in an intimate scene between the leads. The Copa América final will be the Neymar and Messi show. Brazil and Argentina play two of the most extreme versions of hero ball you’re ever likely to see, because they happen to have the two best players on Earth. Simply by occupying a position between the two stars, Brazil’s left midfielder will be stuck with the thankless job of supporting Neymar and defending Messi at the same time. It’s a lot for a Fred.

Brazil has a longer history than it would care to admit of starting what you might call spiritual Freds. The 1994 World Cup is still a shameful scar on the national psyche, not because Brazil didn’t win — they did! — but because they won the wrong way, in a defensive 4-4-2 anchored by Mauro Silva and Dunga, “two bruisers who could not play together.” O jogo bonito this was not. To make things worse, Dunga was appointed to manage the national team not once but twice in the past 15 years, and each time built a plodding side in his own image. "Does Brazil no longer impose its style, its rhythm and dominate the game against any opponent because we no longer have outstanding players in midfield?" lamented Pelé’s onetime attacking partner Tostão in 2009. "Or because coaches, progressively, have changed the style of the Brazilian game in such a way that the brilliant central midfielders have disappeared?"

Tite, the coach who replaced Dunga in 2016, was supposed to change that, and it’s true that his team has been a hell of a lot more fun than what came before. When prime Neymar is healthy, how could they not be? But building around a singular attacking talent — Tite has called Neymar his “bow and arrow” — means making some pragmatic choices behind him. Casemiro, Brazil’s captain, plays a Dunga-like destroyer role, with world-class center backs backing him up. That still wasn’t enough defensive structure for Tite, who’d rather not risk a 7-1 on his résumé. In a surprise move just before the Copa América, he called up a second bruiser, Fred, to serve as Casemiro’s partner.

You wouldn’t know it now, but Fred started his career playing attacking midfield and even winger for Inter in Porto Alegre and Shakhtar Donetsk, Ukraine’s finishing school for second-tier Brazilian exports. It wasn’t until he got his big-money move to Manchester United in 2018 that he became fully Fredified. “I had to adapt, at Shakhtar I was dedicated to attack and at Manchester to defense,” he said. But he adapted well, developing into one of the most active ballwinners in England. Even though United fans may grumble about their less than inspiring McFred double pivot, they’re not complaining about the results. I asked a few to describe Fred’s Fredness:

- Jamie Scott: “reasonably chaotic, quite loose in possession”

- Maram AlBaharna: “big con is diving and committing into challenges way too early”

- Kees van Hemmen: “hyper effective front-footed defender, good progressive passer with erratic execution”

You can see all that with the national team, too, where Fred can’t resist the occasional sprint into the attacking third or a careless forward pass that gets picked off in Brazil’s half. But when it works, his chaotic side can be pretty damn fun:

Alas, serving as Brazil’s designated Fred is not about having fun. It’s about providing structure and support for the fun-havers. In possession, his job is to get the ball to Neymar and get out of the way. The typical buildup rotation goes like this: Neymar drops from the left wing into the halfspace to receive, Atlético Madrid’s Renan Lodi scoots up from left back to cover the wing, and Fred swings out from the left side of his defensive midfield partnership with Casemiro into the fullback space, where he offers Thiago Silva a safe outlet or else lures a defender out with him to open direct lanes forward. One way or another, the play finds its way to Neymar, who’s got complete freedom to go wherever and try whatever he wants to finish it. Fred’s job is to follow about 10 to 15 yards behind and mop up, circulating possession as needed and rushing forward to counterpress whenever Neymar loses the ball.

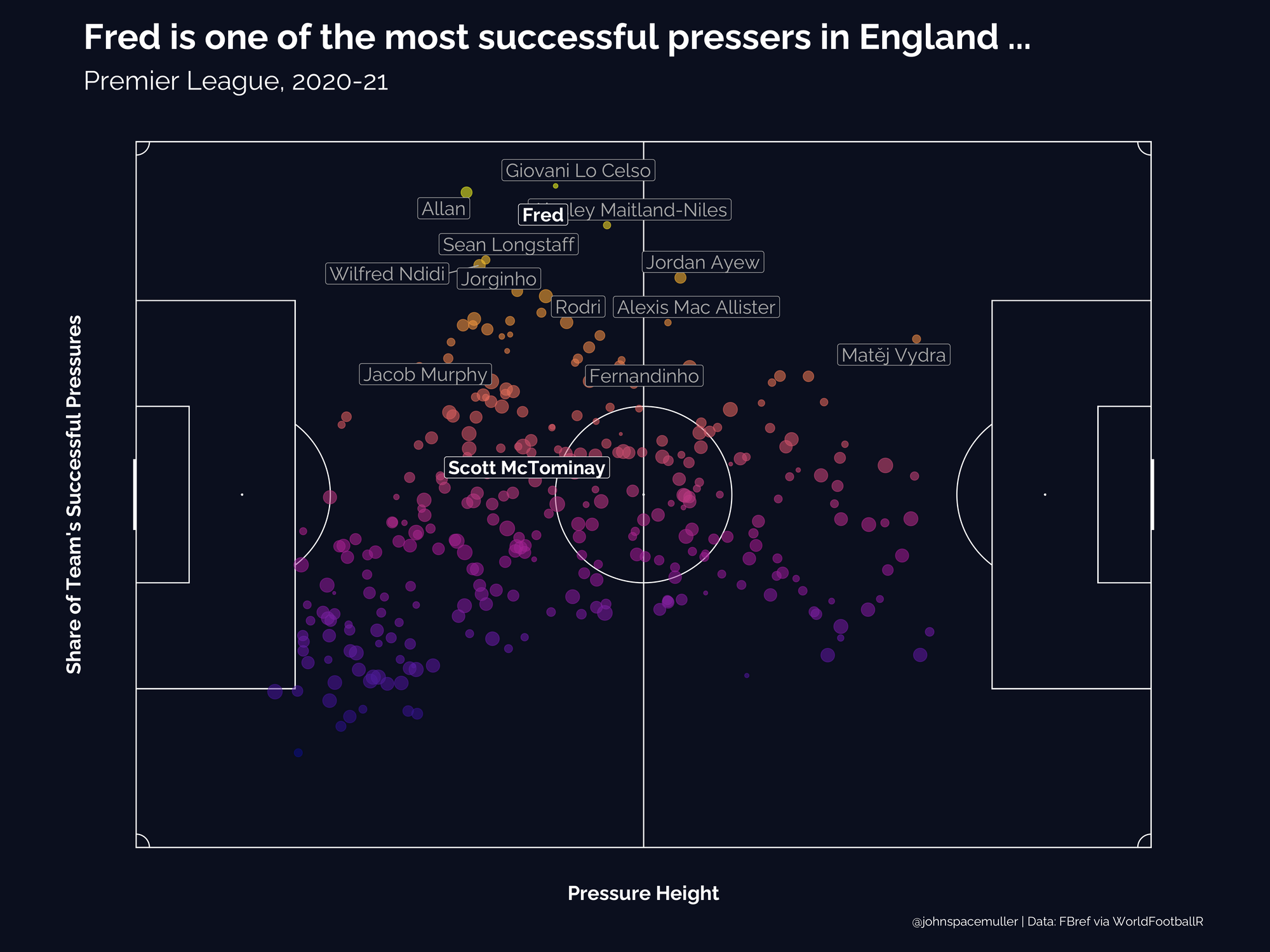

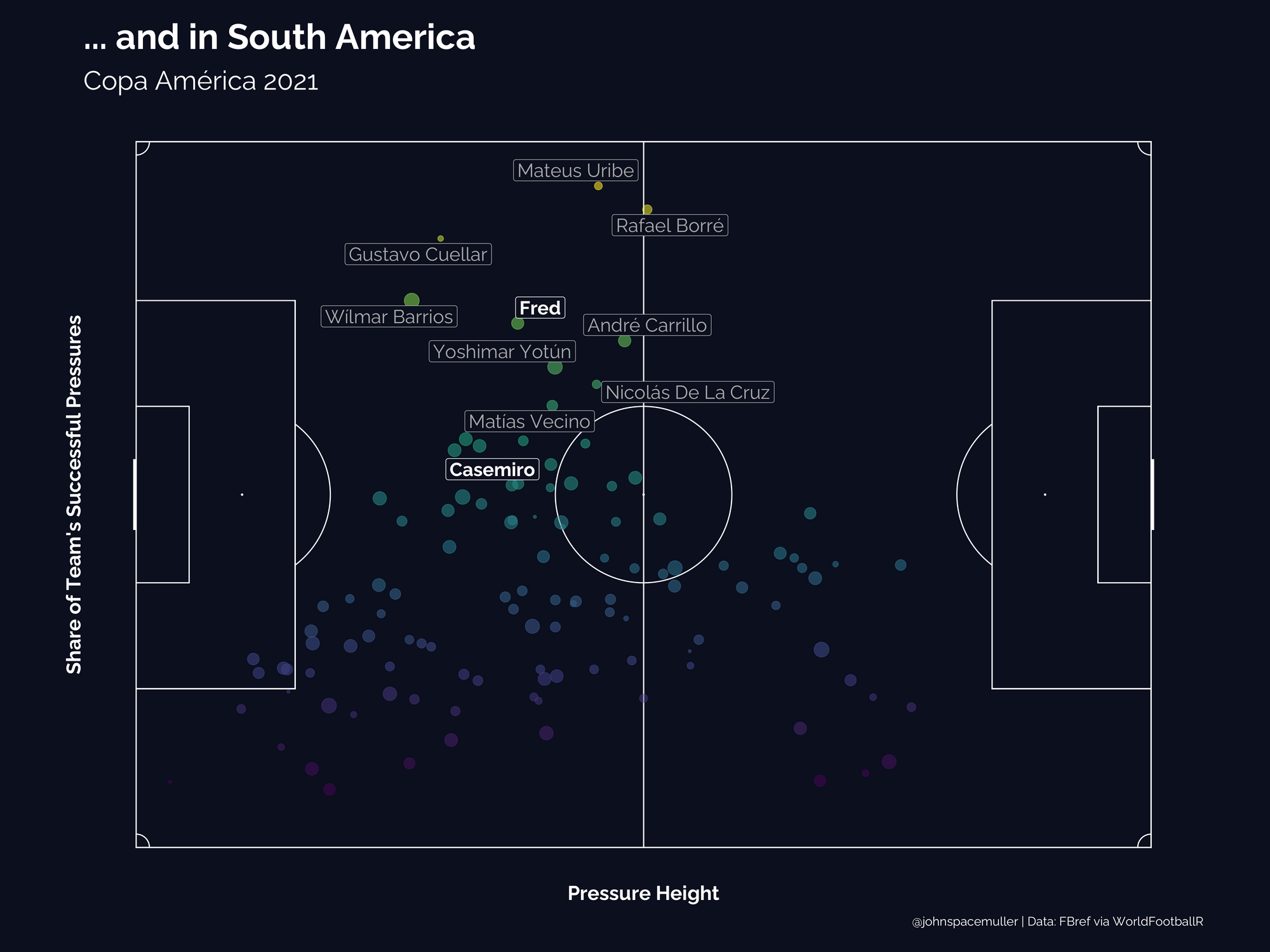

That front-foot defense is the reason Tite picked him for the job. The plot below shows how effective Fred’s pressures are for Manchester United and Brazil. It’s a little conceptually wonky: the x axis isn’t actually the average height of a player’s pressures but a proxy for it derived from FBref’s pressure data (which is provided by third of the pitch); the y axis isn’t actually a player’s share of team pressures while on the pitch but his per 90’ rate divided by his team’s per 90’ rate. I know, boring nerd stuff, whatever. Point is, farther right means the player presses higher up the field, and farther up on the viz means he does a lot of pressing that helps win the ball back. Fred tends to engage in the middle and defensive thirds, where successful pressures are more common, but even there he stands out for how often his closing down helps his team recover the ball. Compare him to his club and international teammates Scott McTominay and Casemiro, who defend in roughly the same area of the field but don’t successfully pressure the opponent nearly as much.

Okay, cool, so Fred is aggressive in defense. Usually that’s a good thing. It’s why he’s here. He takes good angles, switches alertly from man to man, and forces the other team to slow their roll after a turnover so his team has time to recover. But every once in a while, like Maram pointed out, he’ll get a little too excited and bite early in transition. That can be a problem when you consider the sheer size of the Fred Zone that he has to protect. Remember, the left back Lodi is all the way up on the left wing by the time Brazil crosses the halfway line. The left center back, Thiago Silva, is very good but also very old, and you can’t count on Neymar to help out on D. Pretty much the whole left side of Brazil’s midfield is Fred’s problem every time Neymar tries some stuff that doesn’t come off.

When you’re playing Venezuela or Ecuador, sure, Fred can cover all that space, no sweat. But when you’re playing Argentina ... you know who works that Fred Zone in transition, yeah? That’d be their shotgun quarterback, Sr. Lionel Andrés Messi. And Messi wants this trophy very, very badly.

Fred has a choice in the final: stay tight behind Neymar and help Brazil counterpress, which risks leaving Messi unmarked behind him, or shadow Messi and watch Neymar cough the ball up with no backstop, which could allow Argentina to break forward with numbers. There’s no right answer here, but Brazil’s hopes of a historic win at the Maracanã, and their chance to purge a disappointing last decade, depend on one hardworking, unassuming man — the Freddest Fred you ever saw — never getting it wrong. ❧

Further reading:

- Carl Anka, What is Fred? (The Athletic)

- Tim Vickery, As Cup looms, Brazil hopes to extend magic ride that began in '94 (Sports Illustrated)

- Raisa Simplicio, Parreira: Brazil’s 1994 World Champions did it without the ball (Goal)

Image: Brazilian feathered imperial coat of arms

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.