What we can and can't measure about how to set up a cutback.

I’ve been thinking this week about different kinds of cutback.

On Tuesday Sevilla spent ninety minutes tearing Dortmund open at the seams, sliding little daggers in from wingers with chalk on their boots for midfielders in the channels to pull back. The next day City filleted Southampton with long inside-out balls from the middle to runners on the wings, who pushed the defense back before looking for a trailing shooter. Just a minute ago, while I was writing this, United scored the goal that’ll probably seal their Champions League spot next season thanks to a cutback that didn’t even work. Mason Greenwood got a ball to his feet on the right touchline, dribbled into the box all by his lonesome, and slung in a low cross that West Ham tipped away, only to concede on the ensuing corner.

I’m not here to convince you that cutbacks are a good thing. Of course they are. You’d probably look at me like I’d told you that chocolate ice cream is, in fact, yummy. What I’m saying is they’re not really a thing at all—not a single kind of soccer play but a whole suite of strategies for breaking down a defense that happen to share a similar-looking final ball. You can’t just tell players “do more cutbacks” and watch the magic happen. To get from a key pass type to a useful tactic, you’ve got to back the thing up and think about what all the different kinds of cutback are, how they’re created, and which ones are and aren’t worth trying to build an attack around. Y’know, analysis.

For some dumb reason I decided to try this with data.

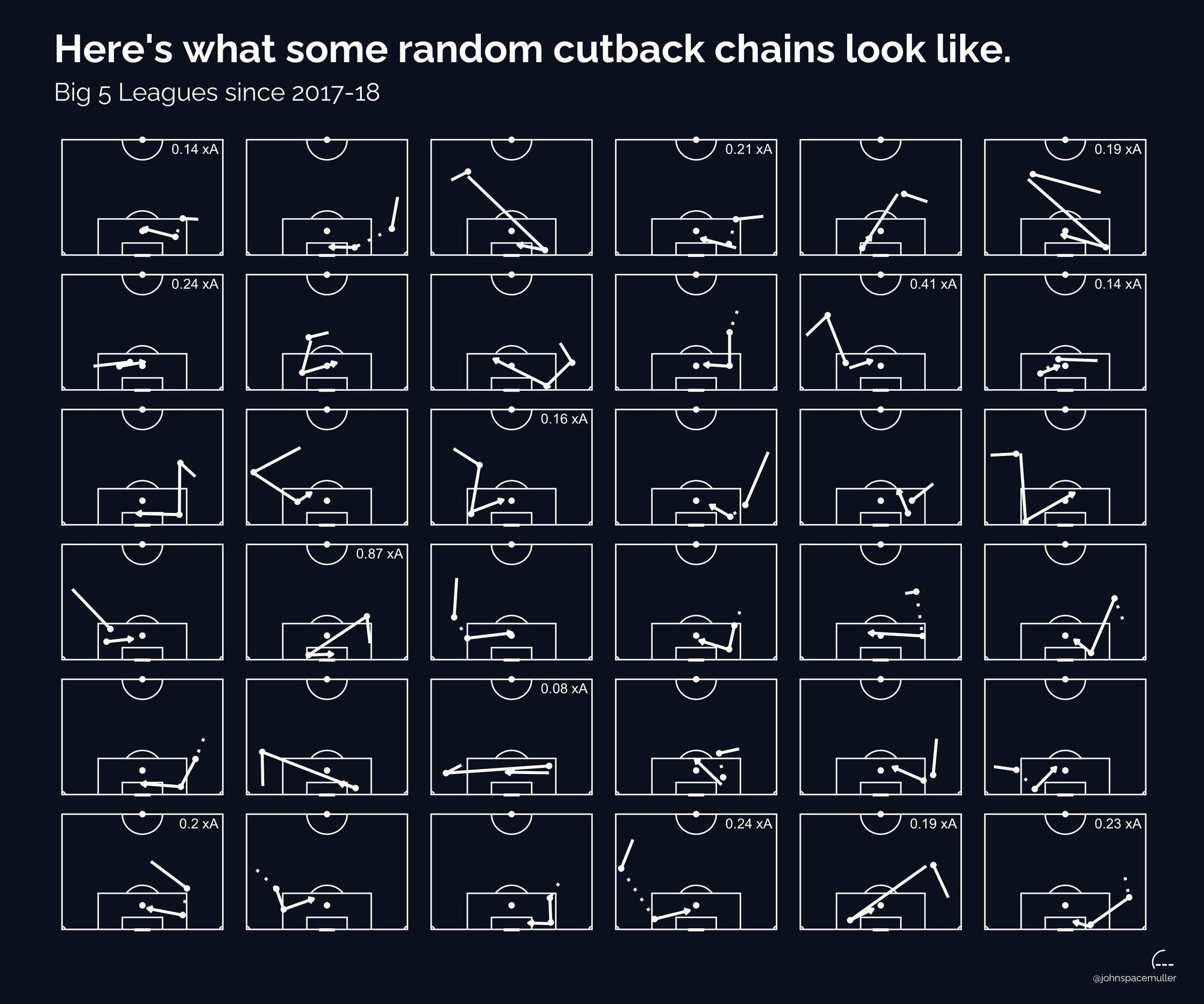

Event data, you’ll remember, only tells you what’s happening on the ball. Sometimes that’s enough to dig up something interesting, like the stuff I’ve been writing about over the last month as I’ve been learning to code in R. Other times all it gives you is mysterious stick figures like this:

You remember that cave art in “Twin Peaks” that they stare at for like half a season before Deputy Andy realizes it’s a map? That’s kind of how it feels trying to imagine these points and lines as soccer highlights. Like, okay, I can sort of accept that the long dotted diagonal in the bottom row means a carry like Greenwood’s, and the little 0.24 xA in the corner means it found a trailing runner to set up a good shot. Maybe I can stare at this grid until I notice some matching patterns, like that kids’ card game Memory but for grownups with fewer friends. To really analyze this stuff, though, it’ll probably help to break out the k-means clustering algorithm from last week’s letter on goal kicks.

For our purposes, a cutback is a square or backward pass longer than five yards, played with the feet, from the zone bounded by the edge of the box, the six-yard box, and the penalty spot. After we mirror the ones on the right to match the ones on the left, the cutbacks themselves all look more or less the same. The thing we want to taxonomize is the pass before the cutback, like so:

Cool, yeah, now it feels like we’re starting to get somewhere. Grouping the pass before the cutback not only gives us some labels to talk about how Sevilla’s play in Type A ...

… is a very different soccer move from the Dias-to-Zinchenko-to-Foden number in Type C ...

… it also lets us start measuring how they compare. Over the last four seasons in the Big 5 leagues, Type A cutbacks have been tried more than twice as often as Type C, but the latter are 50% more likely to produce a goal off the cutback. That’s useful to know when you start thinking about the risk-reward tradeoffs involved in setting up these plays, sort of like it was helpful last week to break goal kicks into types for measurement purposes.

But there are a few reasons analyzing cutbacks isn’t as easy as “like the goal kick thing, but backwards.” One big one is that cutbacks happen in all kinds of situations, without the tidy sameness of a set play. Nearly half of all cutbacks are set up not by a pass but by a carry, which changes the whole speed, geometry, and number of players involved in getting behind the defense. Better give these their own set of clusters:

Now we’ve got twelve paths to a cutback, some more common or productive than others. Type B cutbacks, set up by straight-ahead throughballs from shallow positions in the halfspace, lead the way with 79 assists over the last four seasons. That’s followed by 70 from Type V, where a player receives around the corner of the box, dribbles to the endline, then pulls it back. The marathon carries in Type W may be fun (Wolves’ Adama-Neto attack likes them) but they’ve produced a grand total of nine goals over hundreds of combined team-seasons, so probably not a strategy you want to bet the farm on.

| Cluster | Cutback Attempts | Share of Cutbacks | Total Goals | Goals per Cutback |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 743 | 11% | 36 | 0.048 |

| B | 1047 | 15% | 79 | 0.075 |

| C | 366 | 5% | 26 | 0.071 |

| D | 820 | 12% | 52 | 0.063 |

| E | 350 | 5% | 28 | 0.080 |

| F | 722 | 10% | 34 | 0.047 |

| U | 715 | 10% | 46 | 0.064 |

| V | 755 | 11% | 70 | 0.093 |

| W | 224 | 3% | 9 | 0.040 |

| X | 227 | 3% | 25 | 0.110 |

| Y | 454 | 7% | 19 | 0.042 |

| Z | 531 | 8% | 40 | 0.075 |

We can also look at team-level trends. Manchester City, who’ve been synonymous with cutbacks for years, seem to have fallen out of love with the tactic, attempting just 1.21 per game in 2020-21 from a high of 2.34 per game 2018-19. (Maybe they’re missing David Silva, whose new club, Real Sociedad, has suddenly leaped into the cutback elite.) Across all four seasons in our sample, the cutback-happy clubs are the ones you’d expect: City, Bayern, Barcelona, and other perennial Champions League contenders. They’re followed by less dangerous but more cutback-centric attacks like Sevilla and Arsenal, always trying to walk it in.

I thought maybe it’d be cool to see which particular patterns certain sides favor, but cutback attempts from our narrow zone are so rare that the samples are too small for that. I made you a little video anyway featuring some teams that seem to be good at a certain type of cutback, just for fun:

If I were thinking of building a game model around cutbacks, there’s so much more I’d want to know. What phase of play do different types happen in? Which channel are the pass receivers taking to get to the cutback zone? On a pattern like Type A, is it better for the player who passes out to the wing to be the same one who runs the channel to receive the next pass, or should three different players be involved? Where are the runners in the box coming from? You could maybe make a little headway on this stuff with player names and positions, but the limits of my data are the limits of my world. At some point you’re going to need tracking data, film study, and a big helping of tactics theory to go much further.

But there’s an even bigger question lurking in the background: Are cutbacks even worth it?

We know these passes tend to produce high-value shots when they come off, but we also know they don’t come off that much. We can measure how often certain cutback patterns are attempted and how often they score. If we wanted, we could run the expected pass completion rate of the different clusters and discount each pattern by how hard it is to set up. But the questions about value and probability only get thornier from there. It’s pretty easy to complete a shallow pass out to the wing to set up a play in Type F, and much harder to work the ball to the edge of the box to set up Type D. And what about opportunity cost: If you’ve got the ball at the edge of the box, are you better off attempting a cutback pattern or passing into the middle? These are the arguments that must have kept Pep Guardiola and Juanma Lillo up at night when they decided to retool City’s attack to be less reliant on cutbacks.

I don’t have answers to the big game-modelly questions, but I think it’s cool that we’re getting closer to a day when we can think of them as things we can try to measure rather than the stuff of pure tactics theory. New kinds of data will help. In the meantime, my guess is teams should probably try to set up Type B cutbacks from shallow positions in the halfspace. Oh, and if possible, try to sign David Silva. ❧

Image: Twin Peaks (1991)

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.