On Lionel Messi and the limits of juego de posición.

“Sometimes coaches will make it too difficult,” Ronald Koeman said before Barcelona’s first Champions League game. He was talking about balancing a team’s organization with players’ individual qualities—standard coaching stuff, but not so simple when your best player thrives on disorganizing the game.

“We have Messi in the team, and the rest, they need to do a lot of work, a lot of running, because then Messi can still be the best player in the world,” he said. “And that means every player playing in their position.”

How quaint. In their position. How charmingly old-fashioned, like beseeching players to remove their bowling hats at the supper table as a gentleman ought. Positions, as anybody on Football Twitter can tell you, don’t exist. Maybe they never did. What modern soccer has instead is juego de posición, which—don’t let the name fool you—is basically the opposite of positions. Got it?

Okay, yeah, maybe we should back up.

From Positions to Posición

In the beginning, there was chaos. Proper Victorian association football was a game of chasing the ball and dribbling at goal. Then passing happened, and some changes to the offside law, and lo, teams parted into guys who scored goals and guys who stopped them. Pretty soon they started to arrange themselves into shapes that occupied space in useful ways and put players in roles where they could do more of the stuff they were good at and less of the stuff they were bad at. These were called “positions.” Everyone agreed for decades at a time on which shape was best, the 2-3-5 or W-M or 4-2-4, and the Lord saw that it was good, or at least good-ish.

It’d be a stretch to say that a handful of hippies in Holland invented modern soccer tactics, but maybe not that much of a stretch, because they kind of did. Under a coach named Rinus Michels in the sixties, the Dutch powerhouse Ajax started shrinking the field with a high offside line and pressing aggressively in the compact space, which helped them dominate possession. In the last decade almost every good team has agreed that’s the best way to play soccer, but half a century ago it felt risky, and not necessarily in a good way.

Nor were Ajax’s defenders content to be aggressive off the ball. “I had to let midfield players and defensive players participate in the building up and in the attacking,” Michels is quoted as saying in Jonathan Wilson’s Inverting the Pyramid. “The most difficult thing is not to teach a fullback to participate in attacking—because he likes that—but to find somebody else who is covering up. In the end, when you see they have the mobility, the positional game of such a team makes everyone think ‘I can participate too. It’s very easy.’”

The “positional game,” as Michels used the phrase, meant what it said: the game was organized around positions, with players free to rotate among them. If a fullback felt like doing winger things for a while, a winger would simply drop back and become a fullback. This style got branded “Total Football,” but—crucially—it began less as an idea than a shared understanding. The players that came up together at Ajax also formed the core of the Dutch national team; they spent their whole lives playing together, which made position-swapping easy, almost natural.

“People couldn’t see that sometimes we just did things automatically. It comes from playing a long time together. Football is best when it’s instinctive,” said the defender Barry Hulshoff. “Total Football means that a player in attack can play in defense—only that he can do this, that is all. You make space, you come into space. And if the ball doesn’t come, you leave this space and another player will come into it.”

Instinctive football. Making, occupying, and leaving space. We’ll come back to all this.

Anyway, these Ajax and Dutch teams had a player named Johan Cruyff. You’ve heard of him, yes? Cool, we’ll keep things moving. Cruyff transferred to FC Barcelona in 1973. It was a big deal. “Back then football was ‘right, out we go: come on lads, in hard’ and that was it. No one studied the opponents, it was: fight, run, jump,” the winger Carles Rexach said. (Rexach, incidentally, is the guy who’d go on to sign a 12-year-old Lionel Messi to Barça on a paper napkin.) Even as a player, Cruyff changed the club’s culture. “There was a method, an idea,” Rexach said. “We brought that to the game and other teams couldn’t handle it.”

By the time Cruyff came back to coach, Barcelona’s identity was inextricable from Dutch soccer. When his Dream Team won the club its first European Cup in 1992, there were former Ajax stars in the attack and the defense—to the extent those words meant anything to a side descended from totaalvoetbal. “I was a defender who wasn’t really a defender,” said the squad’s Dutch center back. “I scored so many goals because I used to step forward out of defense a lot, and my coaches asked and expected me to do that.”

That non-defender defender was, of course, one Ronald Koeman. We’ll come back to him too.

But here’s where things get complicated, because it turns out that just being Dutch, or even being Dutch and a former Ajax manager, doesn’t guarantee you’ll think about the game the same way as Johan Cruyff. When Barcelona brought in Louis Van Gaal a couple years after Cruyff left, they thought they were hiring his heir. Instead, as Michael Cox recounts in the opening chapters of his new book, Zonal Marking, they’d found Cruyff’s nemesis. Both coaches preached the gospel of Ajax, at least in its broad outlines: building from the back in a 4-3-3 or 3-4-3, defending with a high line, and pressing in the opponent’s half. But Van Gaal rejected the instinctive position swapping that had defined Total Football. In fact, he pretty much rejected instinct in general. He wanted structure. He talked about playing soccer as the execution of “basic tasks.” “Football is a team sport, and the members of the team are therefore dependent on each other,” went a typical Van Gaal lecture. “If certain players do not carry out their tasks properly on the pitch, then their colleagues will suffer.”

Cruyff was the more successful coach at Barcelona, where he’s still a saint. (“Cruyff built the cathedral,” Pep Guardiola famously said when he took charge at the Camp Nou; “our job is to maintain it.”) But Van Gaal became a key figure in modern soccer in his own right, thanks less to his mixed managerial record than his influence on Guardiola and especially Juanma Lillo, who’s now Pep’s second-in-command at Manchester City. Lillo, in case you’re new to the whole soccer hipster world, is famous for three things. The first is being one of the game’s great aphorists. The second is formalizing—inventing, if you’re trying to sell papers—the 4-2-3-1 formation (more on that in a previous space space space). The third is his association with juego de posición.

JdP. Positional play. There’s been no hotter buzzword in soccer the last five years; whatever meaning it might have once had has been beaten out of it by a thousand contradictory blog posts and ten thousand jargon-ridden Twitter threads. It’s not clear it ever meant much more than a general idea with a bunch of loosely related sayings and a fancy foreign name. But that general idea is a pretty important one.

Before Van Gaal, Cox explains, tactical organization “was often only considered an important concept without the ball; teams defended as a unit, while attackers were allowed freedom to roam.” The “basic tasks” guy put the clamps on that in a hurry. His players “were supposed to occupy space evenly, efficiently, and according to Van Gaal’s pre-determined directions.” The notion that that you could structure play and occupy space using not just positions in the traditional sense, as player roles in a formation, but with positions as zones on the pitch gave coaches a language to teach more detailed, orderly possession play. “There’s a line that unites Laureano Ruiz, Michels, Kovács, and Johan Cruyff,” Lillo once said, “but, look, the one who contributed most to juego de posición is Van Gaal.”

It’s possible to read Guardiola’s coaching career as an arc from Cruyff to Van Gaal. Blessed like Michels with a squad that played together from their academy days to the World Cup, Pep was happy to teach his Barcelona players certain tactics and leave them to improvise others. Dutch-style position swapping was the norm. Football is best when it’s instinctive. At Bayern Munich and Manchester City, as his rosters got more geographically and ideologically diverse, Guardiola’s managerial style got more exact, mechanical, efficient—and also more influential. Training pitches across Europe are now waffled with grids like the ones Pep, like Van Gaal before him, draws to teach players to think about their spacing and movement as the ball moves from sideline to sideline, box to box, phase to phase. You make space, you come into space.

Elite teams no longer have formations; they have whole sequences of well-drilled shapes. Like under Cruyff, players are given freedom to improvise, but like under Van Gaal they operate under detailed instructions that emphasize structure in possession. Your teammate goes here with the ball, you go over there to stretch the defense. Players don’t just swap positions, they swap temporary spaces and functions to make sure their team has numbers on the next line and a free man with space to turn. This is how the game is played from Manchester to Milan. To paraphrase Elena Kagan, we are all de Godenzonen now.

The Positionless Player

All of us, that is, except Lionel Messi.

There are certain privileges that come with being the greatest player of all time; one is you get to do whatever you goddamn please on the field. “Messi plays with complete freedom and he can change his position as he wants. He’s the best in the world in every position,” Luis Enrique once said, speaking on behalf of every coach he’s ever had. “If he plays as a No. 9, a No. 8 or a No. 6, he’s the best in the world. He’s total football and we’d be very stupid if we imposed limits on him.”

Luckily for Barcelona, what Messi wants is several steps ahead of what you think you might want from him. He’s a flâneur, a peripatetic thinker, strolling around sizing up the defense’s weaknesses. Lots of players can dribble and pass and shoot—not many can do any of them on Messi’s level, let alone all three, but his ability to interpret the game has always been an underappreciated strength. As Bobby Gardiner once wrote about some analytics work by Javier Fernández and Luke Bornn showing how he manipulates defenses: Messi walks better than most players run.

What Messi won’t do is defend, at least not with the kind of consistency you can plan your press around, nor will he drop what he’s doing to cover for his teammates. What do you expect from a genius? Faulkner made a terrible postman; Eliot had a mental breakdown working in the basement of Lloyds Bank. But Messi’s total disinterest in the drudgery of systems makes it hard to coach Barcelona with grids and instructions. He’s best improvising off the instincts of other geniuses like Andrés Iniesta and Dani Alves and Neymar. If you don’t have any geniuses handy, your next best bet is to train a hard worker like Ivan Rakitić to do the positional play thing in the buildup and then pull an old-fashioned position swap whenever Messi feels like being a midfielder. Despite what Luis Enrique said, moving Messi back to the wing five years ago was a subtle way of imposing limits, of giving him creative freedom in his favorite right halfspace while maintaining the team’s structure.

Ronald Koeman has different ideas. He’s given up pretending that Messi’s a wide player and decided to sacrifice a center mid in favor of a right winger, spreading the front line and at least theoretically restoring some horizontal balance to the attack. For the first few games the formation looked like a caved-in 4-2-4, with Coutinho or Pedri working under or alongside Messi, but in his first Clásico last weekend Koeman switched things up again, playing a weird 4-2-3-1 with Ansu Fati (not a striker) at striker and Coutinho and Pedri (not wingers) on the wings. The commitment to ignoring positions was admirably Dutch. In a general places-and-roles sense, at least, you could see what he was going for. “Our plan was to have control,” Koeman said, “to change Leo’s position, put Ansu up top for his speed, and have two players on the touchline with good ball control.” He gave his own tactics a passing grade.

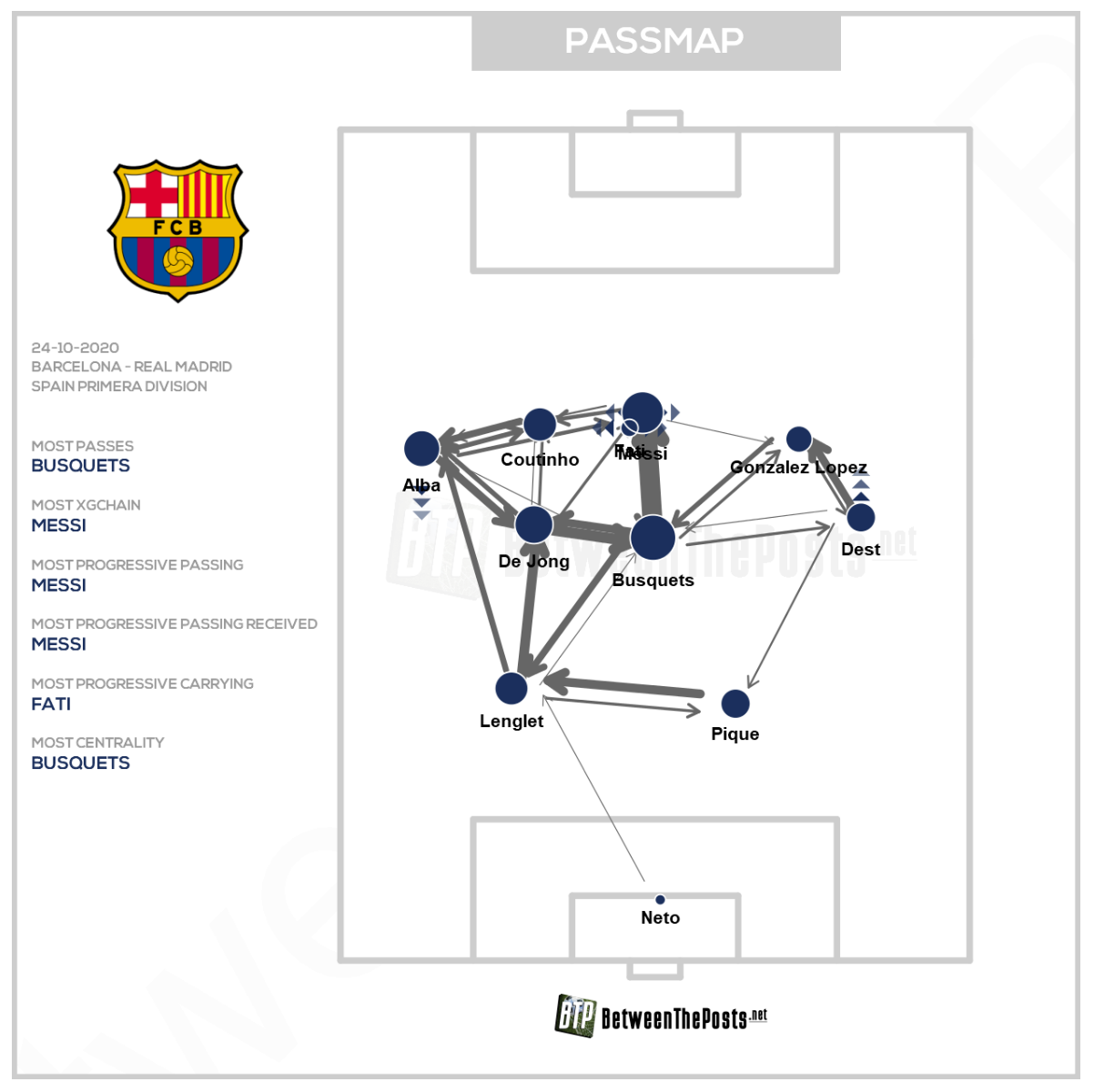

When you get down to positional play, though, the thing was a mess. The basic idea seemed to be that Barcelona would build up in a 4-2-3-1 with Frenkie de Jong dropping out left to send Jordi Alba up the wing and bring Coutinho inside, a pretty standard rotation. Past the halfway line, Busquets would anchor the midfield while Frenkie pushed up between the lines to make a 4-3-3 shape alongside Messi. Finally, Barcelona would finish with an overlapping Alba arriving behind an outnumbered and outmatched Nacho. On paper this all makes sense. What doesn’t make sense is mapping out shape changes by phase on the assumption that Messi’s going to play along. What’s that thing they say? If you want to make God laugh, show him your plans.

Instead of staying put as a central attacking midfielder, Messi dropped between, behind, and even out left of the double pivot, causing visible confusion as his teammates tried to figure out who was supposed to rotate where. His improvised overloads did what he wanted them to—the first time he dropped out left, he set up Barcelona’s goal with a beautiful ball over the top to Alba—but at the cost of structure. Even when he stayed put, he was a hole in the middle of the defense. Frenkie would push up to help, but that left Busquets isolated as the only center mid in 40 yards of space between Barcelona’s lines. Again and again Madrid plucked the ball away from Barcelona’s overloaded left side, waltzed across an empty midfield, and attacked the opposite wing with Vinicius Jr. one-on-one while Ferland Mendy underlapped. Total Football’s high and tight pressing game this was not.

In the end, Barcelona failed at both kinds of positional play. They couldn’t do Van Gaal-style structure because Messi was in midfield and Messi doesn’t do rules. They couldn’t do Cruyff-style position swapping because they’re on their third coach and third major formation change this year after the last one got, uh, suboptimal results against Bayern Munich. If Koeman decides to leave Messi in the middle long enough, he and his teammates will figure something out—like Hulshoff said, instinctive football comes from playing a long time together. But the coach’s job is going to be just a tad more difficult than telling everyone to run hard and “play in their position.” ❧

Thanks for reading space space space! If you like this stuff, please consider becoming a socio to support the project and get the Friday letters. Last week's was on Florian Neuhaus's incredible throughball and the analytics case for audacity.

Further reading:

- Jonathan Wilson, Inverting the Pyramid (Bold Type 2013)

- Sid Lowe, Fear and Loathing in La Liga (Nation 2014)

- Michael Cox, Zonal Marking (Bold Type 2019)

- Jonathan Wilson, The Barcelona Legacy (Blink 2018)

- Bobby Gardiner, Messi Walks Better Than Most Players Run (FiveThirtyEight)

Image: Nancy Doughty, Quilt, Contained Crazy Pattern

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.