Everyone wants a left-footed right winger. But should they?

One of the more baffling choices at the Euros involves Phil Foden. No, not the Slim Shady hair. I’m talking about Gareth Southgate’s insistence on playing him at right wing. Like yes, definitely, Foden is very good, and even in a squad as stacked as England’s it makes sense for the manager to want him on the field somewhere. But why on the right?

Consider: Raheem Sterling, who’s also in England’s first-choice eleven, lined up on the right eight times in all competitions for Manchester City this season, according to Transfermarkt. Marcus Rashford played there nine times for Manchester United. Bukayo Saka, Foden’s backup, is a regular on Arsenal’s right wing. Southgate’s also got Jadon freaking Sancho, which, yeah, let’s not get into that right now. But Foden? Out of 63 appearances in his young Premier League career, only four — a whopping 6% — have come on the right. What’s he doing there for England?

The obvious answer, the only way this almost makes sense, is that he’s supposed to come in on his stronger left foot. Over the last decade or two, soccer has moved away from fast wingers who beat defenders up the sideline to lay in crosses and toward wide creators who cut in to play incisive passes or shoot. When Foden did that five minutes into England’s tournament, you could see Southgate’s vision for how this was supposed to work:

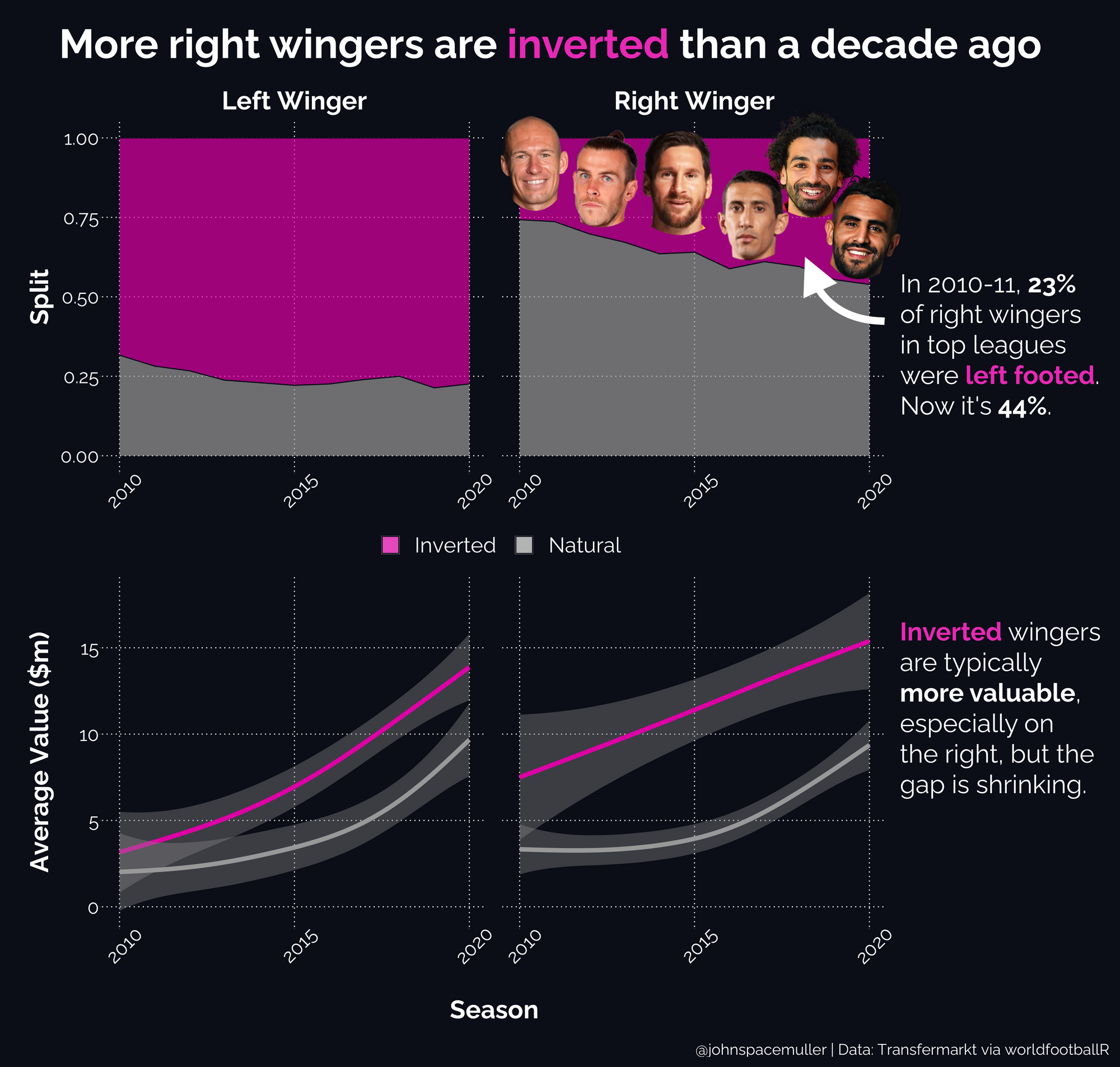

And yeah, sure, if that’s the kind of play you’re looking for from your right winger, conventional wisdom says you need a left footer who can shield the ball as he’s cutting across a fullback and curl a shot to the far post. Foden and Saka are England’s only left-footed wingers, so they’re the only guys who’ve started on the right. Simple, right? Lately most coaches in Europe’s top leagues have agreed that’s the way to go.

As recently as a decade ago, there wasn’t even a good name for wingers who played opposite their strong foot. In 2010 a young Michael Cox blogged about a game where Valencia was using the left-footed Juan Mata, of all people, as a natural left winger to stretch the sideline on the counter. But Quique Sánchez Flores’s Atlético Madrid was doing something different: “Simao and Reyes were again deployed as inverted wingers,” Cox wrote, bolding his coinage for emphasis, “the right-footed Simao on the left, the left-footed Reyes on the right.” (He later tweeted that the term at the time was “‘inside-out wingers,’ which I was absolutely not having.”)

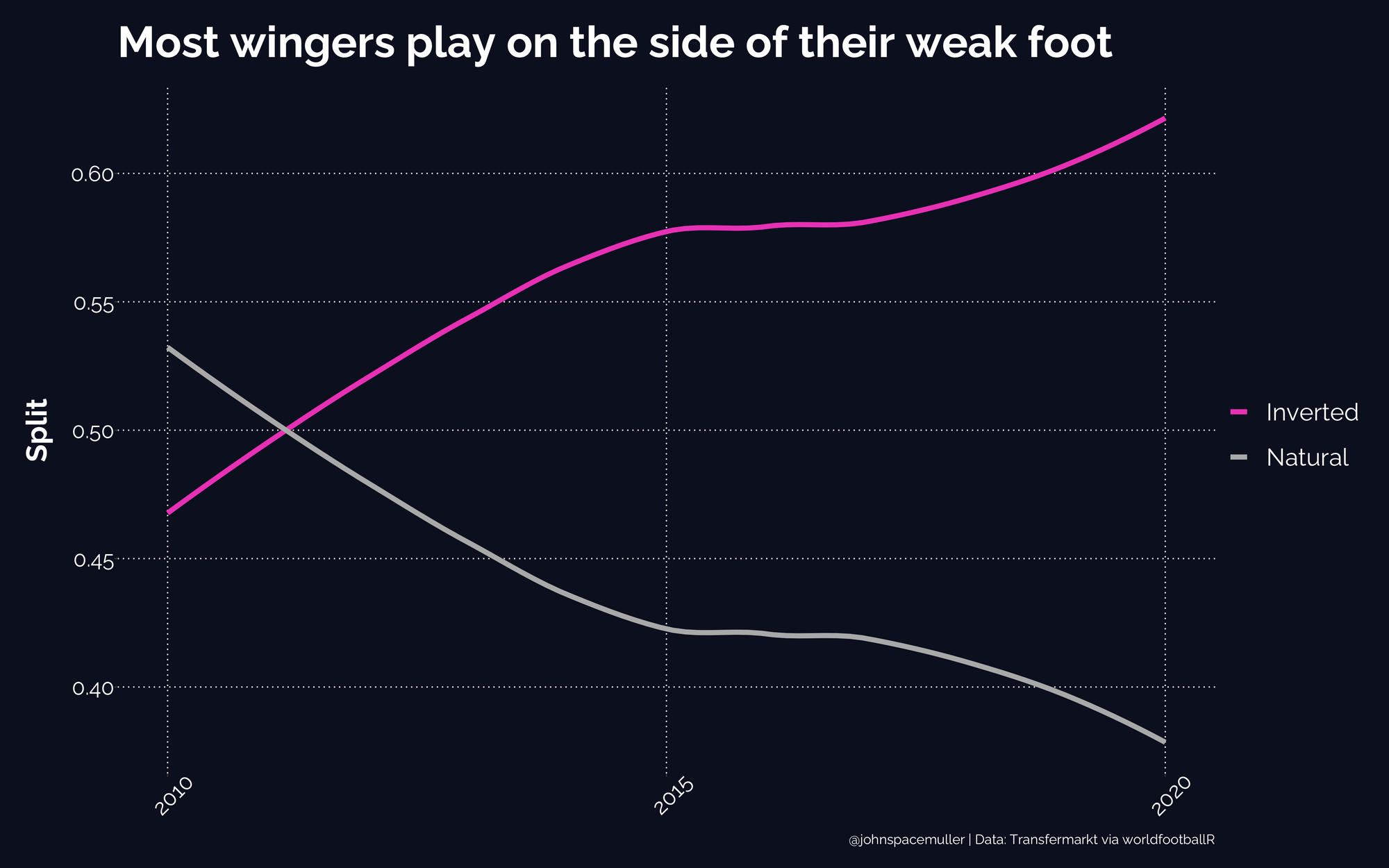

Inverted wingers have gradually taken over the game, but biology hasn’t made it easy. About 70% of professional soccer players are right-footed, 25% left, and 5% “both” or unspecified. (We’re still going off Transfermarkt here, which I’m pretty sure leaves player footedness up to the wisdom of the crowd, but you could doublecheck this against FBref’s Statsbomb data if you wanted.) A lot of left footers get funneled to left back, where they’re practically mandatory, leaving the winger pool at just 28% lefties. Even back in 2010 most left wingers were already inverted for the simple reason that most players are right footed; the big shift has been on the other side, where the share of left-footed right wingers has doubled in the last ten years.

But just being a left-footed right winger doesn’t make you Arjen Robben. Wingers can be a lot of things. Instead of giving us a consensus on the one true way to play, the shift toward inverted wingers has produced more variety, turning what used to be a simple job — dribble, cross, repeat — into a whole bunch of different possible roles. Here, I made you a little cheat sheet:

Traditional Wingers

In the bad old days, teams defended deeper and attacked faster and most wingers stayed wide, where playing on the side of their strong foot helped them beat defenders up the sideline and square it to the strikers. Almost no good team plays this way now. Even Atlético Madrid, soccer’s last great 4-4-2 purists, have moved away from it lately. That’s true at the Euros, too, where almost none of the favorites uses a wide, natural right winger to get to the endline and cross. That job tends to fall to a right wingback like the Netherlands’ Denzel Dumfries or Germany’s Joshua Kimmich, who operate more or less like traditional wingers, or an overlapping right back like Spain’s Adama Traoré, who plays a lot of right wing for his club but did his dribbling outside the inverted winger Pablo Sarabia against Slovakia.

The one notable exception to the no-traditional-right-wingers rule is Italy’s backup Federico Chiesa, who looked lethal staying wide in a 4-3-3 and beating poor young Neco Williams to the endline against Wales. Kind of feels unfair that the most tactically creative team at the tournament has two different kinds of right winger to clobber you with.

Wide Playmakers

As the 4-4-2 gave way to the 4-2-3-1 and 4-3-3, the next big thing for wingers was cutting inside to shoot or play a forward pass into the box. Think young Lionel Messi, young Gareth Bale, or the ageless timelord Robben. But that “young” part is usually important for mortals who live in linear time, because to make this trick work — receiving out wide where it’s easy to get on the ball, then picking a moment to flick the ball across the left back and beat him inside — you need the defender to be scared enough that you might beat him to the outside that he’ll hang back and leave room for the cut. You need him to know you’re fast.

It’s not easy to find elite speed, timing, and close control in one winger, especially on the right where the inverted talent pool is smaller. Sarabia can do it for Spain, but Luis Enrique usually prefers a positional attack that lets his center mids rotate into a wide playmaker role instead of counting on his wingers to win one-on-ones. Foden’s supposed to do this kind of thing for England, but without pace or practice at cutting inside, he’s been bottled up on the right. Bernardo Silva’s fared only slightly better playing wide right for Portugal instead of the inside role he plays for City. The best wide right playmaker type at this tournament has been Berardi. His shots have all come from cutting in on his left, but his one assist came from torching a dude to the outside for a cutback. See? That’s how you earn room to keep coming inside.

Inside Forwards

Instead of starting out wide and dribbling in, a lot of inverted wingers these days would rather receive closer to goal. That can work a couple different ways. Sometimes you’ll see a striker like France’s Antoine Griezmann or Spain’s Gerard Moreno stuck on the right in a four-back system, where they may not offer much on the ball but can crash the box to offer a second scoring threat. The real unicorns are complete inside forwards like Germany’s Kai Havertz, with the technique to play between the lines and the pace to make runs in behind. These guys are a natural fit for the 3-4-3, where Havertz plays pretty much the same role for club and country. Pinching inside makes it easy to swap positions, which Havertz and Thomas Müller do all the time; Jeremy Doku, who looked a lot more dangerous than Dries Mertens in Belgium’s 3-4-3, is a frequent side-switcher too.

But by the time wingers have inverted and pinched in and there’s a defender outside them providing width, are they really even wingers at all? The slow drift of tactics can make it hard to say when one thing turns into another. Lately at the club level it feels like the future is tweeners like Havertz who line up on the right side of the front line but play in the halfspace, part attacking midfielder, part second striker, only occasionally wide. Maybe one day the whole idea of wingers will feel hopelessly dated, like sweepers or halfbacks or predictions that Turkey will be a dark horse.

Driving Wingers

There’s one more trendy type that we haven’t really seen much at the Euros: wide natural wingers whose job is to stretch the defense off the ball more than on it. They stay as high as possible and hug the touchline to give the attack width, but they’re more like to dribble at a defender and square a ball across the face of the defense instead of around to lay in a cross. But where these guys really make their money is diagonal runs in behind a fullback to turn a throughball in the channel into the perfect cutback. Chiesa could probably do this for Italy if he didn’t love dribbling so much; Ferrán Torres could do it for Spain if they played a little more like Pep Guardiola’s City, where he’s been learning the role.

You know who else does this for City? Sterling (on the right, sometimes) and Foden (on the left), opposite how they’ve been used at the Euros. If this whole inverted winger thing doesn’t work out for Southgate, maybe he could try playing a little more like the best soccer team in England. ❧

Thanks for reading space space space! Please consider becoming a paid member to get more letters like last week's on how Pedri scans.

Also: I'm planning a newsletter on scouting and need volunteers to watch a couple games over the next few weeks and evaluate a player. If you're interested in helping out, email me at john@spacespacespaceletter.com or DM me on Twitter.

Image: Candido Portinari, Somersault

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.