Possession adjusting has problems. But how else can we account for opportunity?

Of all the weird things about Leicester City’s Premier League title run, the weirdest was that they didn’t have money, but a close second was that they didn’t have the ball. That’s just not how good teams play soccer these days. In the five years since that 2015/16 season, winners of Europe’s top five leagues have averaged 62% possession, according to FBref’s Statsbomb data; Leicester attempted just 43% of the passes in their games, the only champion in that time to see less of the ball than their opponents.

That posed a problem for bigger clubs looking to poach their best players. Anyone could see that N’Golo Kanté was a tireless ballwinner and Riyad Mahrez was dangerous breaking up the wing under Claudio Ranieri, but how would they do in possession-based sides where the ball was already won and opponents’ low blocks offered little wing space to break into? Interestingly, the soccer analytics community settled on different ways to address these two questions.

Back when Kanté was bossing Leicester’s midfield it was becoming popular to adjust a player’s defensive stats according to his team’s share of possession. “Player A who averages 5 clearances per game might be better than Player B who averages 6 clearances if Player A's opposition had the ball 20% less often. That would mean player A made more clearances given the opportunities provided to him,” Jared Young wrote for American Soccer Analysis in 2014. Later that year, when Statsbomb CEO Ted Knutson introduced the possession-adjusted defensive stats that still populate the company’s radars, he used the same word: “Tackles and interceptions as they currently exist are mostly just noise because they don’t account for opportunity.”

For some reason, though, the idea that the opportunity to record stats depends on which team has the ball never bothered people quite as much on the attacking side. Instead of using elaborate possession adjustment formulas, people looking at offensive production have preferred to stick a wet finger in the air: “Ah, this player’s shot stats aren’t tremendous," as Mark Thompson put it, "but on a better team in a better attack they’d probably pick up.” We slapped a per-90-minutes adjustment on attacking stats like Mahrez’s expected goals but stopped there. Opportunity, as far as these numbers were concerned, was simply a function of time on the pitch.

Sports stats have always struggled with how to account for opportunity. In Moneyball, Michael Lewis recounts how Bill James launched baseball’s sabermetrics movement with assaults on two traditional stats, errors and runs batted in. The problem with errors as a measure of fielding ability wasn’t just that they depended on the scorekeeper’s judgment of whether a fielder should have gotten to a ball but that, in James' words, “you have to do something right to get an error.” The easiest way to avoid errors is not to reach for tough balls in the first place. RBIs, which require a batter’s teammates to get on base before he comes to the plate, have the opposite problem: the opportunity to record them depends on a factor over which a player has no control at all. “The problem,” James wrote, “is that baseball statistics are not pure accomplishments of men against other men, which is what we are in the habit of seeing them as. They are accomplishments of men in combination with their circumstances.”

Soccer is a hurricane of circumstance. We can count up who accomplished what how many times, but to use those numbers for what we want them to mean (how good is a player at doing things? how many things would he do in different circumstances?) we have to account for a lot more than the trajectory of a ground ball or the number of baserunners. When we adjust a player’s stats, we’re trying to capture not just what a player did or didn’t do but how much opportunity he had to do those things and—this is the hard part—what role the player himself had in creating that opportunity.

Possession adjusting never pretended to get you all the way to isolating ability, but it seemed like an intuitive enough way to gain some ground on the opportunity problem. “Teams that have a ton of possession don’t give their opponent the ball very often, and thus can’t accumulate defensive stats,” Knutson wrote in his introduction. “What do you do when you know the basic rate stats are meaningless? You adjust them. Hopefully in a way that isn’t completely terrible, but we’ll wait and see on that.”

So Statsbomb put possession-adjusted tackles and interceptions on the radars and waited for something better to come along. “I knew we basically always wanted to shift to a different framework,” Knutson told me when I asked him about possession adjusting. But six years later, no popular alternative has really taken off. You’ll still see “padj” player stats pop up not just on Statsbomb’s stuff but on various homecooked player vizzes floating around analytics Twitter. When Tom Worville wrote “The 10 Commandments of Football Analytics” for The Athletic, he suggested adjusting tackles and interceptions per 1,000 opponent touches. “Possession-adjusted defensive numbers give a more rounded view of defensive activity,” Worville wrote, “but these still only show style and not overall quality.”

Maybe it’s the hopelessness of defensive event stats as a measure of quality that’s made us more willing to fiddle with them. In Ryan O’Hanlon’s No Grass in the Clouds newsletter last week, American Soccer Analysis’s Sam Goldberg said he had “strong feelings” against adjusting for possession on the attacking side. “Let's say you're a counterattacking-based team with really super fast wingers,” Goldberg told O’Hanlon. “That team thrives on not having the ball. But now if you adjust possession for them, that's not a true reflection of how someone might play if they were possession dominant, because then the defense has to drop a little bit deeper, and there's not as much space for wingers to run into.”

The Mahrez problem, in other words. But when I asked Sam how we would know if various methods of trying to adjust for opportunity got us closer to “true” performance than plain vanilla rate stats, he got quiet for a minute. “That is a good question,” he said. “Let me ponder.”

When Knutson introduced Statsbomb’s possession adjustment in 2014, he proposed checking to see whether it improved defensive stats’ relationship with the outcome defenses actually care about, preventing goals. A team’s unadjusted tackles and interceptions have no correlation to its shots and goals allowed, but using Statsbomb’s padj formula the r-squared “generally shoots up in the .4 range, which is about the same as you get for possession itself,” Knutson wrote. This “assumes that adjusting defensive stats by possession to increase correlations makes sense and doesn’t simply fall on its face from a methodology standpoint. The logic behind it makes sense to me, but I’m just some guy who works in gambling, not a Ph. D. in stats or math.”

I’m no expert either, but I’m not so sure this makes sense. If tackles and interceptions are noise before they’re possession adjusted, how do we know they’re not noise after? It seemed suspicious that the relationship between possession-adjusted defensive stats and shots against was the same as for possession itself, so I tried possession adjusting some other stuff. An MLS squad’s average height last season had no correlation to its expected goals against, but after adjusting player height for possession using Statsbomb’s formula, I’m happy to report that Carlos Vela stood a more respectable 7’9” and the r-squared between padj squad height and xGA was 0.25—the same as for possession itself. (I asked Kevin Minkus, a data scientist who works with soccer clubs, to explain whether this meant possession was doing all the lifting here and he replied with a bunch of stuff about “interaction terms” that I didn’t really understand; let’s just assume it’s complicated.)

Another problem for possession adjustment is that, despite what you’d think, a team’s possession percentage doesn’t have a whole lot to do with its number of tackles and interceptions. Across the top five European leagues in 2018/19, the last season whose numbers weren’t wrecked by the pandemic, the correlation between possession and squad tackles plus interceptions had a weak r-squared of 0.16. It’s not that shocking, in other words, that the team with the most tackles and interceptions out of 98 European sides (Huddersfield) actually had slightly more possession than the team with the second-fewest (Bournemouth).

So why is possession adjusting still so popular? Knutson told me that some clubs he’s worked with have found it useful in recruitment, but he’s not too attached to what he calls “a bit of legacy analysis work.” The biggest obstacle to trying out new kinds of adjustment is getting everyone comfortable with a different kind of number and making sure it’s easy to communicate. As long as Statsbomb is planning its next step, Knutson figures, “there’s not zero utility in continuing the data hack until we offer up a different framework.”

It’s fun to think about what other kinds of adjustment could look like, and if you poke around there are already possibilities out there. For starters you’ve got the round number school, along the lines of Worville’s per 1,000 opponent touches adjustment. The late Garry Gelade found that adjusting attacking stats per 100 passes rather than per 90 minutes made them more stable and less likely to flatter players on good teams. Knutson says Statsbomb is considering a “per X possessions” scheme similar to basketball’s common per 100 possessions adjustment.

But while adjusting for some number of possessions helps solve the problem of pace, it’s messier than in basketball for the simple reason that soccer possessions are messier. NBA possessions almost always travel from one end of the floor to the other and usually end in a shot; soccer possessions can start anywhere on the field and rarely end in shots. In fact it can be surprisingly hard to even define what constitutes a possession in soccer. That means there’s no guarantee that comparing a set number of possessions ensures players have similar opportunities to record stats. “How many [possessions] are valid? How many are dangerous?” Knutson asked me. “How do you modify player stats based on that?”

We’ll take up those questions—and look at other possible ways to adjust for opportunity—in a future letter. ❧

Thanks for reading space space space! Please consider becoming a socio to support the project—monthly or annual memberships are 30% percent off this week (and no, this isn't an Athletic thing where they're always 30% off). This weekend's premium letter will be about Getafe's unique pressing style.

Further reading:

- Ted Knutson, Introducing Possession-Adjusted Player Stats

- Mark Thompson, Possession adjusting or not possession adjusting. That is the question. (geom_mark)

- Tom Worville, Explained: The 10 Commandments of football analytics (The Athletic)

- Garry Gelade, State-Trait Properties of Football Metrics (Business Analytic)

- Ryan O'Hanlon, How a Former Minor League Baseball Player and a Neuroscience Student Are Redefining What Happens on the Soccer Field (No Grass in the Clouds)

- Jared Young, Individual Defensive Statistics: Which Ones Matter and Top 10 MLS Defenders (American Soccer Analysis)

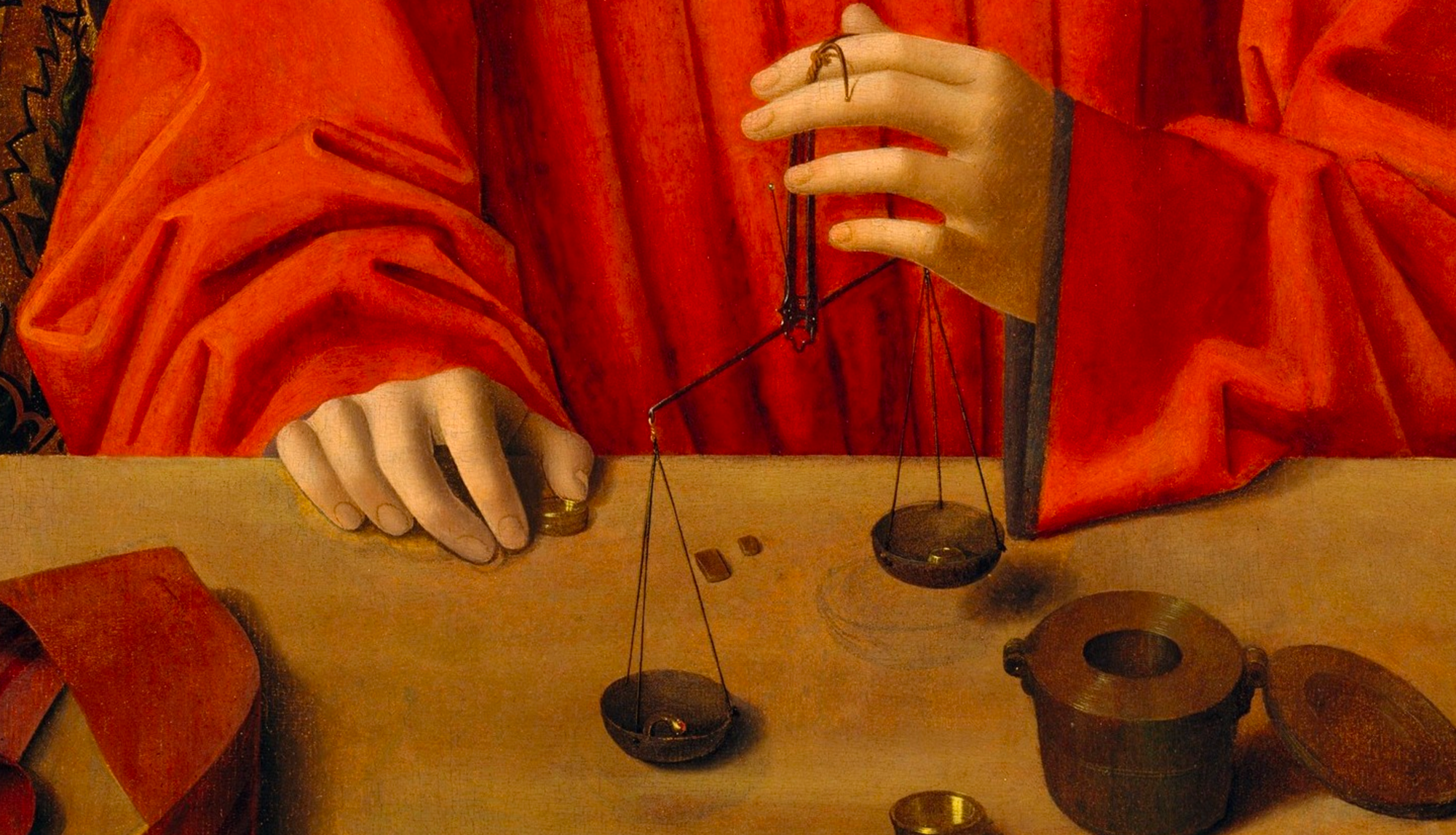

Image: Petrus Christus, A Goldsmith in His Shop

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.