To appreciate how Thomas Tuchel finally made Jorginho and N'Golo Kanté make sense together, watch how they turn on the ball.

Like a lot of space space space projects, this one started with me being dumb and wrong.

Look, it wasn’t my fault. Blame Xavi, Andrés Iniesta, and Sergio Busquets. Barcelona’s Guardiola-era midfield was what made me fall in love with soccer, seduced by all that tiki taka that made a chaotic sport look easy. But when that’s your guiding vision of what the game ought to look like, you wind up with some pretty bizarre ideas about how it works. For example, I’ve always felt like passing at tight angles is a good thing. Barça at their most hypnotic played fast, one-touch passes to teammates who were already in view, dancing in and out of opponents’ cover shadows to draw pressure and play through it rather than swinging the ball across the field. Here’s an example from an old Clásico:

You can see the theoretical advantage of passing quickly, without turning, without even so much as a shoulder check, since the passer can already see everything he needs to know before he receives the ball. That makes it easier to pick out the next player without getting caught by pressure from behind. String enough of these acute passes together and you can work your way upfield without receiving on the half turn or switching play, just ping and move, ping and move. It’s so fast that defenders who try to press wind up like frustrated villains in a silent slapstick, always looking the wrong way while nimbler opponents spin them in circles and kick them in the pants just for laughs.

Here’s the thing, though: Nobody plays like this. Not latter day Barcelona, not Guardiola’s Man City, not anyone. That’s why sequences like this get clipped for YouTube comps that weirdos like me still watch a decade later — they’re not normal soccer. Because the part Xavi and Iniesta made you forget was that stringing a lot of these tight passes together at speed and under pressure is actually really, really hard, and unless you happen to have a bunch of all-time greats in the same midfield, you probably shouldn’t try this at home.

Of course, it was obvious even back then that Barça wasn’t normal. There’s a well-known research paper from 2014 that found Barcelona was unique in La Liga for its frequent ABCB passing motifs (Player A passes to Player B, Player B to Player C, then C back to B) and infrequent ABCD patterns. Nothing went straight up or across the field; everything was a rondo. In the paper’s key figure, a map of passing styles, all the other teams in Spain are clustered on the right half of the chart, and then there’s Barcelona way off in the bottom left corner, passing to themselves in an empty quadrant.

Still, I always hoped that maybe Xavi and Iniesta had given us a glimpse of something fundamental about soccer, something more useful than “it helps to be impossibly good at it.” I wanted to quantify that thing about fields of view and one-touch passing. I thought maybe if I measured the angle of a pass relative to the previous one, I would find that playing at acute or right angles was somehow inherently better, or that better teams did more of it.

Like I said, I was wrong. But it did wind up teaching me about Chelsea.

Introducing Passing Vertex Angles

To look into the passing angle thing, I needed to know how many degrees a passer turned from receiving one pass to playing the next one. (Take “turned” semi-figuratively here — I don’t have data about how players’ bodies are oriented, only where the ball moves.) Luckily American Soccer Analysis’s Tyler Richardett had already whipped up some trig code that could do exactly that. I stole his code, adapted it for this project, and voilà, this thing I’m going to call a “passing vertex angle” was born. (Yeah, I know the name sucks. Hit me up if you’ve got a better one.)

To keep sidelines, penalty areas, and long carries from messing up my hunt for some kind of platonic truth about passing angles, I limited my sample to midfield passes played no more than 3 seconds and 15 yards away from the previous receipt. Each pass had to be played on the ground and travel at least 15 yards. What I wound up with was a bunch of passes that looked like this:

There’s no real reason to stare at this for long, but if you do you’ll probably notice that very few of these passes are at acute angles. In fact, more than half of the passes in my sample were played at an angle greater than 120 degrees. Turning across your body to open play is way more common than those tight tiki-taka angles I admired.

And not just more common — wide-angle passes are also more effective, for reasons that probably should’ve been obvious in hindsight. Every time center backs circulate patiently in the buildup or a midfielder decides to switch play instead of trying to break lines, that’s a wide-angle pass. If a player has enough space to receive on the half-turn and move the ball forward, that’s a wide-angle pass too. The best passing teams stand out not for playing a lot of tricky, Iniesta-esque passes under pressure but for being able to avoid playing them. Since high-possession teams do a lot of circulating around the defense, waiting for an opening, those wide-angle passes wind up being a lot more commmon and more successful than narrow ones.

Color here is based on American Soccer Analysis’s expected pass model, which estimates a pass's chances of success based on where it happens on the field, the angle, whether it's a longball, and some other possession context. All that yellow on the downward bars means that a pass played after turning across your body is more likely to be complete than some other pass that otherwise looks identical in the data. Pretty cool, right? Another fun little thing to notice here is that in our sample of about half a million passes, the ones played after turning right are slightly more successful than after a left turn, which I guess makes mechanical sense given that most players are right-footed.

Okay, fine, so I was wrong about tight-angle passes being better. But what if they’re played quickly?

Narrow angles (including a wall pass right back to the previous passer) are more likely when you have to play fast than when you’ve got time to turn, but even at less than two seconds on the ball, wide angles are more frequent and more successful. There’s a reason coaches are always talking about receiving with an open body shape. It’s how you — a mere mortal who is not as good at soccer as Xavi and Iniesta — spread the field and move the ball away from pressure toward a free man.

What Passing Vertex Angles Mean for Chelsea's Midfield

Every way I looked at the data, it kept telling me the same thing: Every team plays more wide passes than narrow ones in midfield, and good teams and good midfielders prefer wide angles more than bad teams and bad players do. Still, there are some interesting individual differences even among the elite. I’ve been thinking in particular about Thomas Tuchel’s Chelsea.

Chelsea’s roster is famously a Frankenstein’s mishmash of ideas about how a club with more money than God ought to play. In 2016, Leicester City had just won the Premier League by letting N’Golo Kanté run all over the damn place, so Chelsea bought Kanté. In 2018, Maurizio Sarri’s Napoli was the darling of Europe thanks to Jorginho’s metronomic short passing, so Chelsea hired Sarri and bought Jorginho as a welcome gift. Never mind that this meant Chelsea’s two most talented midfielders came from diametrically opposite schools of soccer. The manager would have to make it work.

Interestingly, you can see some of these guys’ differences in their passing vertex angles:

Kanté almost always receives across his body, preferably to his right. Jorginho also likes to open up to his right, but compared to most midfielders he mixes in a lot more narrow-angle passing, including frequent one-twos. That makes a big difference for what kind of midfield role and playstyle they’re best in.

Jorginho, of course, is most comfortable in a Sarri midfield. Here’s Michael Cox describing Sarri-ball in its purest form:

“Sarri actively encourages his sides to be pressed. His Napoli side was notable for the long periods it spent holding on to the ball in defence, teasing the opposition with quick passes between the defenders, baiting the strikers to push forward from their deep block and engage high up the pitch. Once Napoli succeeded in drawing the opposition forward, they'd cut through their lines with slick one-touch passing, and therefore their attacking was a mixture of Guardiola's possession play and Klopp's quick attacking.”

Jorginho’s tight-angle passes from the pivot were tailor-made to attract pressure and zip through it with one-touch play, sort of like Barcelona’s old tiki-taka but with more vertical thrust once his team broke the first line of pressure. Unfortunately for both the midfielder and his coach, Sarri didn’t have the roster or the leash to get Chelsea playing like Napoli. When Frank Lampard took over last season, Chelsea ditched the fussy stuff and switched to a more conventional, circulation-heavy possession style. Jorginho learned to open up and play more like Kanté, but now that his one special skill — short, closed passing — had fallen out of favor, he looked less like a one-of-a-kind modern regista and more like a mediocre defensive midfielder who didn’t really defend. By this winter, Lampard had dropped him to the bench to play Kanté at the base of the midfield, and fans weren’t complaining.

Then Lampard got fired too, because that’s just what Chelsea managers do, and before Thomas Tuchel had even gotten off the plane in January, he’d already decided to switch the team’s formation from an ungainly 4-3-3 to a 3-4-2-1 that’s been a much better fit. At first fans paid more attention to what the new shape meant for this year’s glamor buys, Kai Havertz and Timo Werner, but it was a pretty major shift in midfield, too. With three center backs behind him and Kanté alongside him to provide defensive cover, Jorginho could get back to pinging it around the back, drawing out opposing presses and opening space over the top for Werner to sprint into. On the right side of the double pivot, Kanté can circulate laterally or receive on the half turn to charge upfield — both jobs better suited to his talents than a center mid’s role in the buildup ever was.

Instead of constantly reminding everybody of Chelsea’s rudderless transfer strategy, Jorginho and Kanté finally make sense together. In Tuchel’s midfield they even make each other better, one stretching the press and the other breaking it:

But the moment Chelsea fans finally opened their hearts and let Jorginho back in came in the first Champions League quarterfinal leg, when he started alongside Mateo Kovačić. Chelsea was swinging possession around the edges of a bunkered defense, one easy wide-angle pass after another, looking for a way in. As the ball reached Jorginho in the middle, he received across his body, opening up toward the right half of the field. César Azpilicueta, pushed up alongside the midfield in his elbow back role, offered a no-risk lateral outlet at about 170 degrees. Reece James was available out on the wing at 150 degrees, give or take. Jorginho took a few steps in their direction. But instead of circulating, he changed his mind, swiveled his hips back inside, and threaded a perfectly weighted ball between defenders that Mason Mount twirled on and scored the opening goal.

I doubt the phrase “90-degree passing vertex angle” popped up in Porto’s post-game review, but it’s exactly why they didn’t see it coming. ❧

Thanks for being a paid space space space subscriber! I'll be back with more Champions League stuff this week.

Further reading:

- Michael Cox, Why the Premier League should be afraid of 'Sarri-ball' once Chelsea master it (ESPN)

- Ryan O’Hanlon, Let Us Now Praise Jorginho (No Grass in the Clouds)

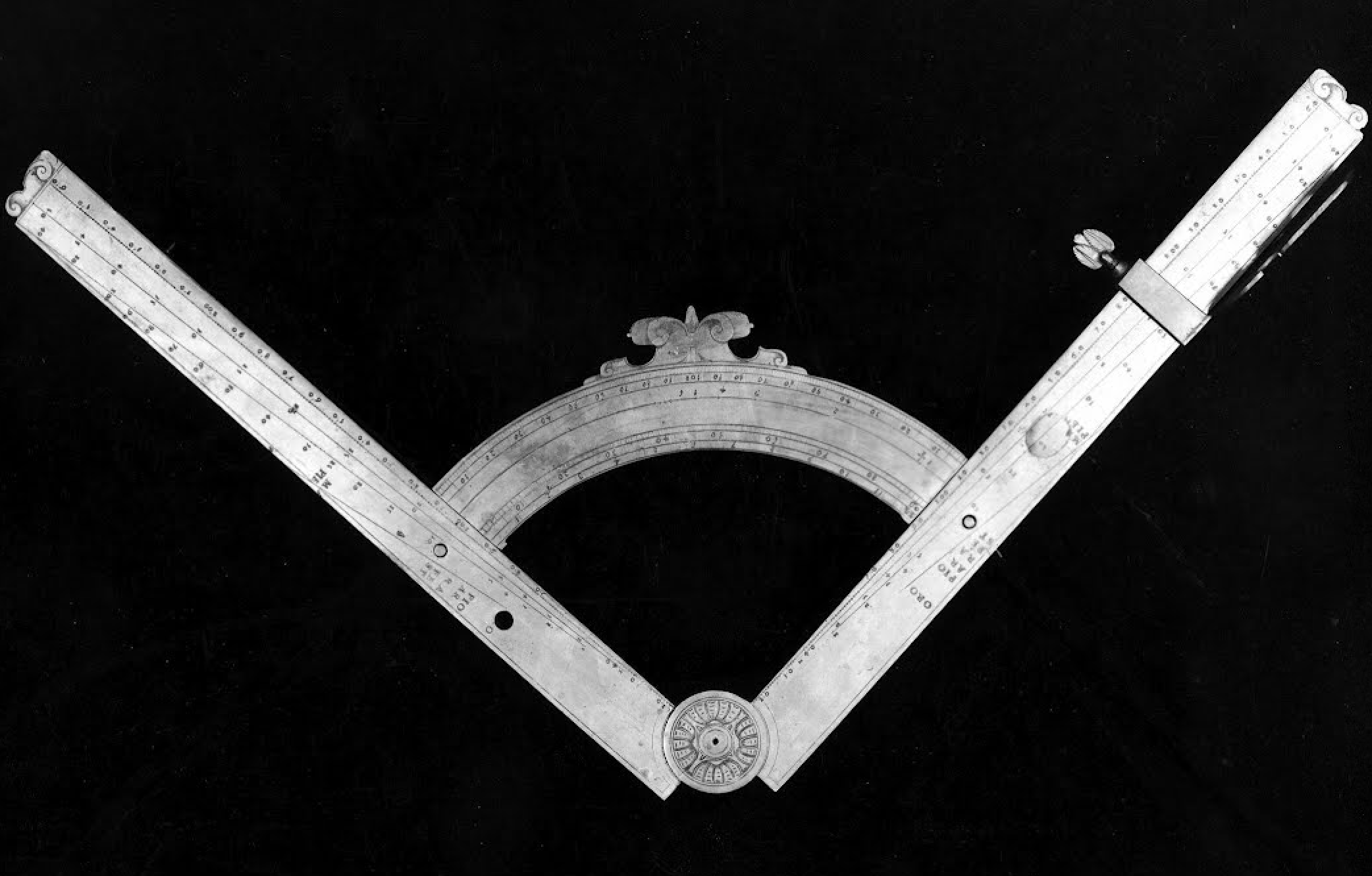

Image: Galileo's Compass

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.