Man City's new tactics are baffling England, but asymmetry works better on the ball than off it.

Asymmetry is everywhere, from snail shells that coil clockwise to nine-foot narwhal tusks grown from a single left canine tooth. Even our brains are a little askew, bulging at the front of the left hemisphere, which specializes in language, and the back of the right, which interprets music and space. Nine of ten people are right-handed; three out of four elite soccer players prefer to pass with their right foot. But when researchers ask people to rank abstract patterns by their beauty, for all our natural imbalance we tend to like complex symmetries more than asymmetrical shapes.

The taste for symmetry has traditionally won out in soccer tactics. Our names for formations and positions assume that what’s happening on the left side of the pitch is mirrored on the right, even though we know the game’s not actually symmetrical. Never was. The tactics historian Jonathan Wilson points out that England’s lineup for the very first international match against Scotland lists more players on the left side than the right, though it’s not clear if it was part of a gameplan or “simply that those were the players available to make the long journey from London to Glasgow.” Most lopsidedness in soccer is just what happens when an idealized geometry meets the living, kicking, lumpy-brained humans on the pitch.

For Man City under Pep Guardiola, asymmetry is no accident. With his assistant Juanma Lillo, a fellow high priest of juego de posición, Pep spent the first half of the season fiddling with his team’s phase-by-phase shapes, evolving from a 4-2-3-1 toward something much weirder, less predictable, and—to judge from their current 14-game win streak, an English top flight record—a lot more dangerous. City might be the most intentionally asymmetrical team in Europe right now. They also might be the best.

City’s system reached its current form in a 3-1 win at Chelsea at the start of the new year. Mark Thompson wrote about it for his excellent newsletter after Pep broke out a double-false-nine version the following week against Brighton, and as he predicted it’s turned out to be not a stopgap but Guardiola’s new thing. Asymmetry is in for 2021.

The single-striker look we saw against Liverpool last weekend has more fixed points than the one Mark wrote about. Phil Foden at center forward was still false-nineish, happy to drop into midfield to help out, but the wingers, Raheem Sterling and Riyad Mahrez, stayed high and wide to pin Liverpool’s fullbacks. The formation would have been a pretty standard 4-3-3 except for one glaring imbalance: every time City had the ball, João Cancelo tucked inside from the right back position to play alongside Rodri as a defensive midfielder. The peculiar, left-leaning shape found balance only when Bernardo Silva swung out to the right flank Cancelo had vacated to force young Curtis Jones to figure out which guy he was supposed to be tracking.

As a possession tactic, Pep’s orchestrated asymmetry was pretty clever. Ilkay Gündoğan, no longer stuck in a double pivot with Rodri like the last time these teams met, pushed up between the lines and found two goals; Cancelo led the team in progressive passes from his midfield spot; and Silva’s free playmaker role let him dictate the team’s shape. Instead of starting in a four-back formation and working their way into a 3-2-5 attacking set, as Guardiola’s been doing for years, the asymmetrical buildup starts from a 3-2-5 and adds width at the back as needed.

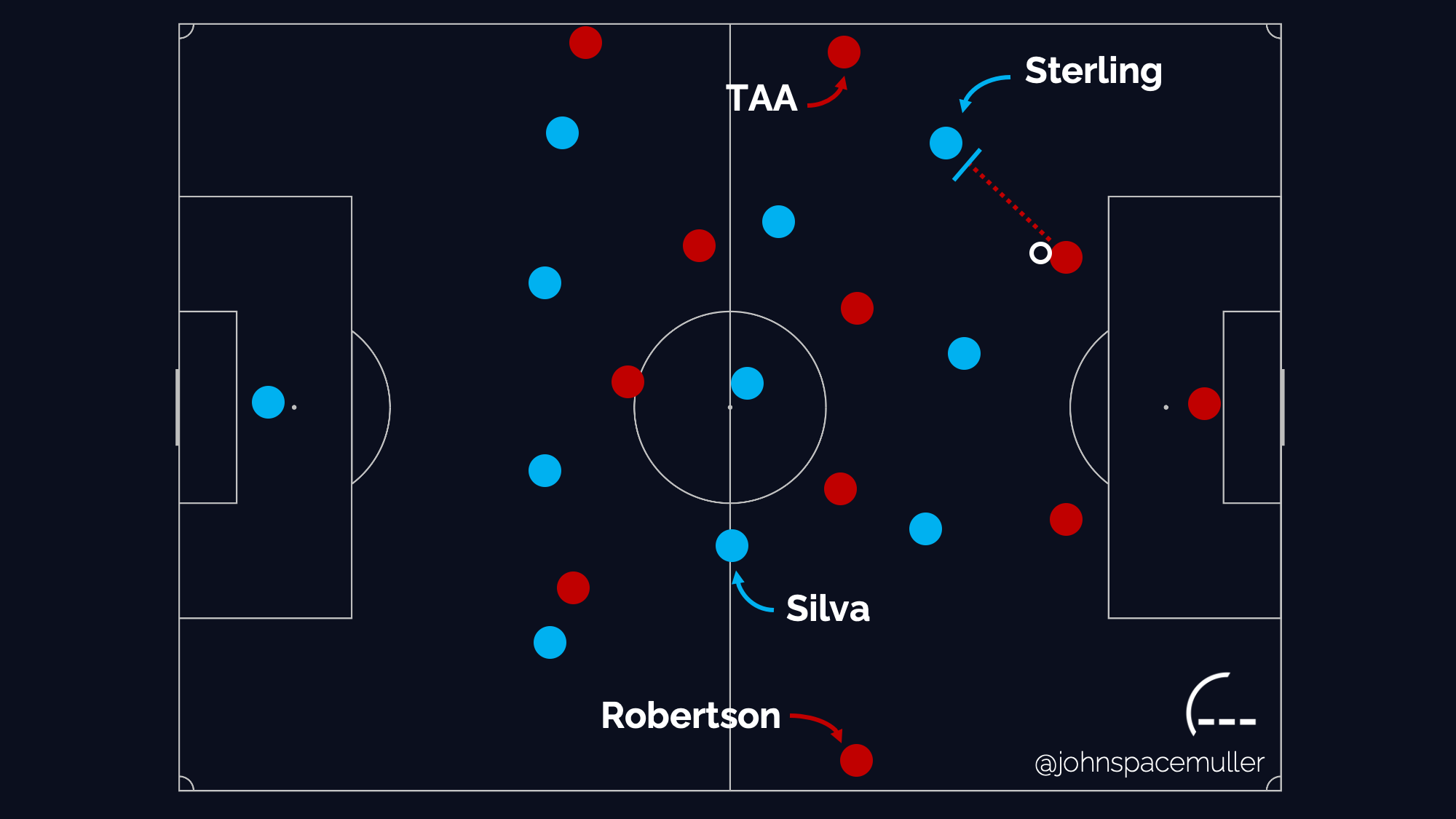

City’s attempt at asymmetrical defense didn’t work nearly as well. They came out pressing in a lopsided 4-3-3 with Sterling pushed high and wide to cut off the angle to Liverpool’s right back, Trent Alexander-Arnold. You could see why: TAA’s been the engine of his side’s buildup this season, contributing to possessions that produce nearly 50% more expected goals than the left back, Andrew Robertson. But Robbo’s no slouch either, and tilting the defense away from him made it too easy for Liverpool to get forward. Silva needed to stay narrow to help deal with Liverpool’s fluid midfield and unpredictable dropping forwards, but he also had to get wide to keep Robertson from waltzing unmarked up the wing. Over on the other side, Liverpool’s fluid midfield found ways to route the ball around Sterling out to Alexander-Arnold, leaving the City winger sprinting back to keep TAA from laying in an early cross. It took about twenty minutes for Liverpool to find a rhythm in possession, but they spent the rest of the first half building through their fullbacks more or less at will, pinning City deep, and turning it into the end-to-end game they wanted.

That changed in the second half, when Guardiola switched to a conventional 4-4-2 in defense and won back control of the game. The newly balanced shape paid immediate dividends for City’s first goal: Sterling, who’d dropped into the midfield four, was in position to pressure Alexander-Arnold into passing backward; Foden and Silva charged into the box as a pair to force a lob that City intercepted; and Cancelo swung from the back line into midfield to play the pass that unlocked the goal. City’s second and third came from structured high pressure too. The team’s different shapes in and out of possession still caused the occasional awkward defensive transition when Cancelo had to hustle back to the right back spot to keep Sadio Mané from receiving on an open wing, but the takeaway from this match is that asymmetry on the ball and symmetry off it looks like the way to go.

Why should asymmetrical shapes work better in possession? It’s about balance and control. “Symmetry isn't essential in football,” Wilson has argued, “but balance is.” City’s lopsided 3-2-5 can achieve balance on the ball whenever it wants by swinging Silva out to the flank. The crooked 4-3-3 in defense was constantly off balance because where Silva needed to be and when—staying tight in midfield or out on the wing defending Robertson—was beyond City’s control. Pep’s po-mo possession tactics may well win him another Premier League title, but in defense there’s still beauty in symmetry. ❧

Further reading:

- Mark Thompson, Pep Guardiola is at it again (Mark’s Notebook)

- Jonathan Wilson, The Question: Do formations have to be symmetrical? (The Guardian)

- M. Michael Cohen Jr., Perspectives on Asymmetry: The Erickson Lecture (American Journal of Medical Genetics 2012)

- Mohammad Majid al-Rifaie et al., On Symmetry, Aesthetics and Quantifying Symmetrical Complexity (2017)

Image: William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience: The Tyger

Sign up for space space space

The full archive is now free for all members.